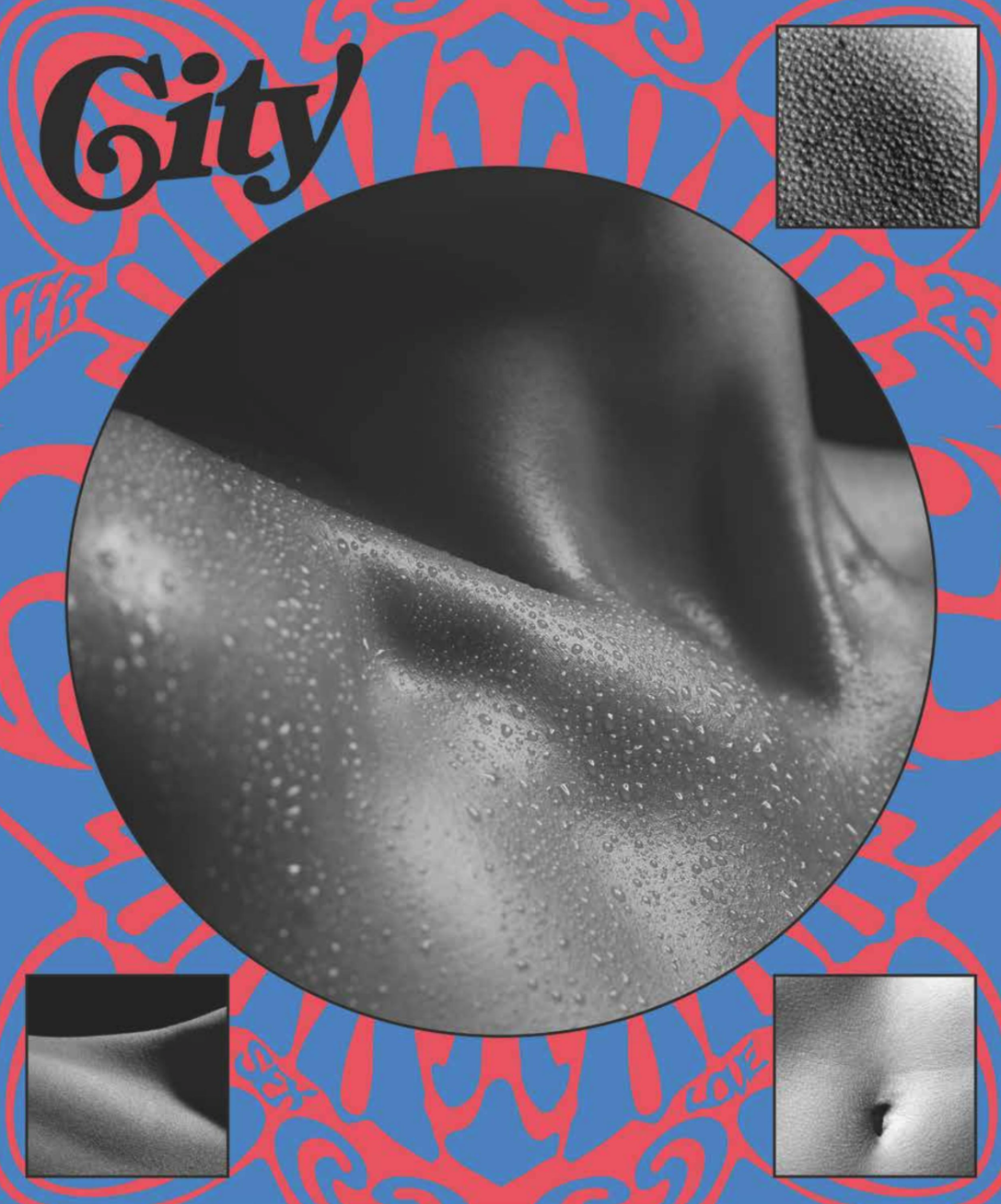

The month of February provides opportunities to celebrate St. Valentine, Body Awareness Month and, perhaps, new and exciting ways to make sure your needs are being met. You may find yourself in the company of someone who you wish to celebrate with, and part of that equation may include breasts. You may have them, have consensual access to them or have had experience with them. But is there any consensus as to what they are for?

In the 1980s, a group of women from Rochester fought for — and earned — the legal right in New York State to make sure that breasts are not for shaming nor restricting those who have them.

Biologically, breasts exist to provide nutrients to offspring. They serve no biological purpose in the act of reproduction and are not required for naturally creating offspring. Yet they remain an incredibly sensitive topic in culture and society. Throughout history, it has been both perfectly routine and grievously taboo to present one’s self topless in daily life.

In 1937, New York granted men the right to be topless in public spaces. This legal protection was not extended to other genders. To complicate matters further, in 1983 New York State adopted The “Exposure Of The Person” law (Penal Law 245.01), restricting public displays of “private/intimate” body parts, including breasts. There were exemptions put in place for breastfeeding, but the lack of equal treatment across genders remained.

In 1986, seven members of local advocacy group CLAW (Challenging Laws [and Attitudes] Against Women) organized an act of civil disobedience. The group planned a casual picnic where people with breasts would go top-free. Leading up to the planned event, the group chose not to notify police of their intentions, but they did issue a press release.

The picnic took place on summer solstice (not a coincidence), June 21, and became a spectacle, distracting from the group’s earnest intentions. News outlets recorded, supporters sat with demonstrators, critics jeered and the police intervened even though it was an orderly event. When asked to clothe themselves, seven of the nine participants refused and were arrested. This was expected, and the ‘TopFree Seven,’ as they were nicknamed, looked ahead to the legal events that followed.

Their subsequent trial on September 16 lasted three-and-a-half days. Rochester City Court Judge Hon. Herman J. Walz rendered judgment in favor of the participants, but not in the way the advocates wanted. Judge Walz ruled their actions were protected by First Amendment rights to personal expression, but rejected the equal-treatment challenge to the exposure law, writing that “there is no fundamental right to appear nude or top-free in public … Today, community standards are perceived by the Legislature to regard the female breast as an intimate part of the human body. Therefore, the state may legitimately enforce this standard by requiring that the female breast not be exposed in public places.”

Since the Topfree Seven were acquitted, there was no path for appeal. As the rendered decision side-stepped the central issue of the newly formed Coalition For Topfree Equality (CLAW, rights advocates, and other supporters), and they had no further legal avenue, it meant they could only continue their advocacy for body equality through more action. Another picnic was planned.

The coalition spent the following years building momentum, raising awareness and advocating for top-free equality. The memorable ad campaign “I’d Rather Be In Rochester” was adapted to end with “Top-Free.” The coalition lobbied Monroe County to designate June 21 as Top-Free Equality Day. And they held more events at city parks as top-free demonstrations — a peaceful picnic including 50 top-free women occurred at Genesee Valley Park in 1988, another top-free gathering happened in 1989 at Durand-Eastman Park and a peaceful walk occurred later that year in Seneca Falls.

All of this culminated on July 7, 1992, when the highest court in New York State ruled that Penal Law 245.01 went against the 14th Amendment’s equal treatment clause and the charges in 1986 and 1989 should be reversed. The New York Court of Appeals decision reads like it was written by the coalition: “Perception cannot serve as a justification for differential treatment because it is itself a suspect cultural artifact rooted in centuries of prejudice and bias toward women … The concept of ‘public sensibility’ itself, when used in these contexts, may be nothing more than reflection of commonly held preconceptions and biases. One of the most important purposes to be served by the equal protection clause is to ensure that ‘public sensibilities’ grounded in prejudice and unexamined stereotypes do not become enshrined as part of the official policy of government.”

Curiously, New York State Penal Law 245.01 is still active. The landmark 1992 court decision does provide legal precedent — where breasts are not inherently defined as intimate or private body parts — but the law still exists. Some may declare that’s irrelevant, the advocates won, the 14th amendment rules the day and all people have body equality under the law. But with the present state of politics and law in this country, perhaps precedent has no legal standing on how a court case or ruling may be decided.

In the meantime, Free The Nipple, FEMEN, The Big Latch On and other TopFreedom movements continue the TopFree Coalition’s work to erase the stigma of baring chests in public. It may seem trivial to even shed light on this part of our society and its advocacy — yet small victories are still victories.

Matt Rogers is a Rochester-based artist and storyteller who works to celebrate urban history, culture and pride in as many ways as possible. Follow him @thelostborough.