[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

The Eastman Museum's Nitrate Picture Show this weekend returns for a fourth year of celebrating the notoriously combustible film format, which was the dominant medium from the dawn of motion pictures all the way through the early 1950s, when the more stable safety film was introduced.

In just a few short years, the event has become an international draw, bringing in film lovers eager to experience a medium that offers a picture of unparalleled vibrancy and clarity, with just a hint of danger. From Friday, May 4, through Sunday, May 6, festival goers can enjoy workshops, lectures, and tours, but the true stars of the festival are the films themselves, projected on glorious nitrate film.

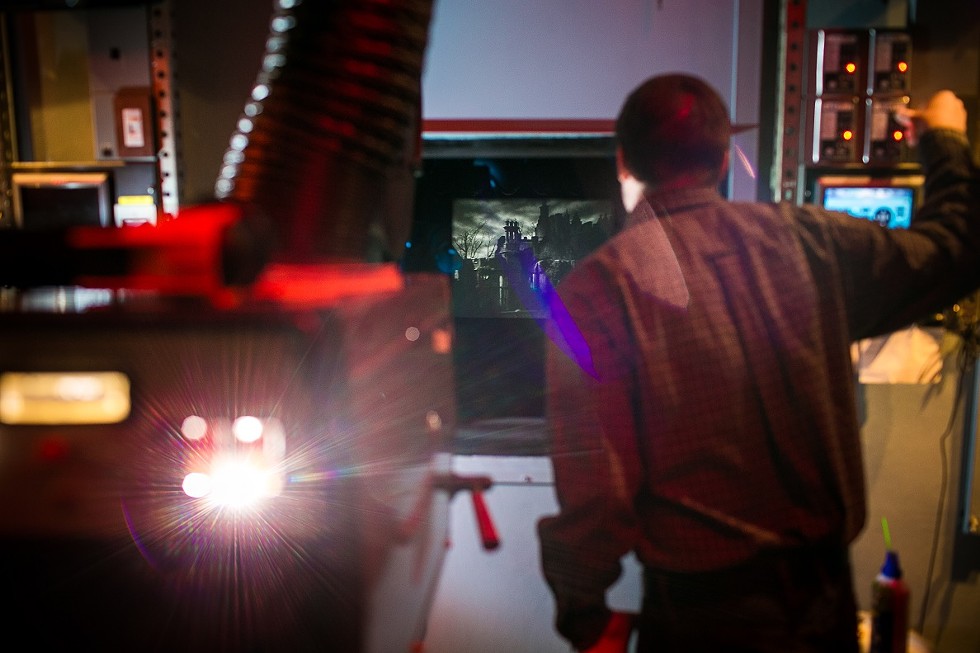

With all eyes on the Dryden's silver screen, the job of making sure the films look their very best falls to the Eastman Museum's team of expert projectionists. CITY sat down with three members of the nitrate team —Chief Projectionist Spencer Christiano, Jim Harte, and Patrick Tiernan — to speak with them about life inside the projection booth, and how it feels to potentially hold the audience's lives in their hands.

If you're interested in a firsthand look what goes on into projecting nitrate, the Dryden's projection booth will be open for brief guided tours after the festival ends, on Monday, May 7, from 9 a.m. to noon. No sign-up required.

Tickets for individual film screenings at the Nitrate Picture Show are $20 ($18 students and museum members) and can be purchased at the Dryden Theatre box office starting Friday, May 4, at 9 a.m. Full festival passes are $150 ($125 for students and members), with a Patron Pass also available for $250. Film titles were announced Friday at 9 a.m., and can be found online at eastman.org/nitrate-picture-show.

CITY Newspaper: For someone who's never seen a nitrate print projected, do you have any tips for things someone should look or listen for when watching the films? Some way to help them appreciate the difference?

Patrick Tiernan: I think what I most appreciate is the contrast. Because of all the silver that's in the print, the whites appear shiny. The blacks are deep and dark. There's such a difference between white and black that you don't get in a non-nitrate print.

Spencer Christiano: The nitrate look is sort of hard to identify. I've heard a lot of people try to define what the nitrate look is, and it's one of those things where when you see it, you'll know. For me it's much more apparent in black-and-white films. For example, a noir nitrate film is the way noir was meant to be seen. You can't get more noir than black-and-white nitrate. The contrast is just incredible. I've also seen some nitrate that doesn't really look like nitrate, and that's one of the criteria that we have for selecting films for the Nitrate Picture Show. Does this have that nitrate look? Does it have that luminance, that radiance, that magic that makes it really pop off the screen? Just because the stock is nitrate doesn't mean that it still has the nitrate look. So we're trying to show the medium in its best portrayal, and not just saying, "This is nitrate, check it out." We're showing the best nitrate that we can find.

I feel like due to the reputation of nitrate, the audience tends to be more conscious of what's happening in the booth during these screenings. Has that been your experience? Do you have the sense there are more eyes on you?

Christiano: The George Eastman Museum is unique in that during any film screening that takes place in the Dryden, whoever introduces the film will also introduce the projectionist; they'll mention whatever equipment we're using, where the print is sourced from, and who's projecting. So it's not uncommon for us to get a few people looking toward the port windows at the beginning of a screening. But everything about a movie theater is designed to make you pay no attention to that man behind the curtain. The audience is pointed away from the projection booth, the booth is generally sound-proofed, and you're not supposed to pay attention to anything that's going on back there. It's our job to make you forget that we exist.

But during the Nitrate Picture Show, I think everyone has a heightened awareness of what's going on, because a lot of people are here in order to see the medium projected and not necessarily to see the particular films. So the technology that we're using in order to exhibit this format is very important to our audience. And I think that they're interested in figuring out what goes on in the booth.

Jim Harte: It's unusual, or maybe even unique, to purposely draw attention to the projectionist. And the museum's been doing that for at least [the past four years]. I like to say we're the puppet masters. Watching a movie, everything about it is an illusion, you know, it's not really moving — or it's moving pictures one at a time — it's an optical illusion, and the audience has a willing suspension of disbelief. So it's a partnership between the presenter, the projectionist, and audience. And part of that is nobody really wants to see the hand of the puppeteer, but we're not a regular movie theater. We're an archival exhibition space. So especially in nitrate, what we try to do is a present movies as they were originally intended to be shown by the director. Or as close as possible to the way the audience saw it when the movie was new.

Christiano: Last year we showed a print from 1913. It wouldn't have been shown in the theater like this; there wouldn't have been carpet on the floors, the seats wouldn't be comfortable. You're looking closer to a flea pit then than an archival exhibition space. But we're kind of trying to give these prints the best possible exhibition that they can have, because in many cases they may never be able to be seen again. This might be their last screening, because nitrate is in many ways an organic object, and it's aging, it's shrinking over time. It becomes more brittle and no matter what archival practices you have, you're still working with an organic compound that will decay over time. So we're hoping that these prints will be able to be projected years and years and years into the future. But I've heard many stories of people who saw a nitrate screening less than a decade ago, and later asked, "Are you ever going to show this print again?" And they're told, "Nope, it's too shrunken now, we just can't show it."

Harte: There's a difference between the nitrate prints and then the negative elements that are in good shape for duplication and are preserved. But sometimes they've shrunken too much to project because the distance between the perforation holes decreases while the distance between the projector teeth does not. So most of these nitrate prints are much louder in the booths than a newer safety print. And some of them sound like a machine gun going off in there.

Tiernan: We have to yell at each other just to be heard. Before I came here, I always thought of projection as like being a referee for a sporting event. You don't want the audience to know your name, because then that means you made a terrible mistake. So every night when they introduce a movie here, they say your name, and so there's pressure to do a good job, to not screw up.

When I've talked with [Nitrate Picture Show Executive Director] Jared Case, he's said that seeing a film projected is like watching a live performance. Is that how you look at it? Do you feel like you're performing for an audience?

Christiano: We have a motto that we use here, that "film projection is a technical art." It's kind of a merging of technical knowledge and the operation of complex machinery with actual physical performance. We're not just standing in front of a projector and pressing a button every once in a while. It's actually pretty carefully orchestrated and choreographed, we're constantly moving in the booth. Especially with changeover projection, while one reel is playing, we're threading up the next reel on the next machine. We're orchestrating the changeover so that there's seamless transitions between reels, we're running down to rewind the film and get it ready for the next screening or get it ready to be shipped back to wherever it's going. We're monitoring the image, we're monitoring the volume level, we're monitoring the entire audience experience. It's pretty hectic.

And when I bring people up into the booth for the first time, they're almost unanimously amazed that this is what goes on in the booth — that it's this complex. I can't tell you how many times I've told people what I do for a living, and I say, "I'm the chief projectionist at the George Eastman Museum." And they say, "Oh, you must watch so many movies!" Sure. I watched, you know, approximately 10 percent of every movie. But the other hundred and ten minutes is spent wearing down my shoes.

Tiernan: We're burning calories.

Christiano: Yeah, my step counter goes wild.

Harte: Each reel weighs 10 pounds and we have to hump it up the stairs. That's why I'm in such great shape. [laughs]

Christiano: We really try not to. We take the same precautions with any film print that we would with nitrate. Like we treat any safety print, any polyester or acetate print with the same amount of care and reverence that we would a hundred-and-five-year-old nitrate print. But of course there's that psychological factor that when you're actually running it through a projector and you're looking at this and saying, "Wow, this is older than, you know... anyone."

Tiernan: This is older than my grandmother.

Christiano: This is older than everyone in this projection booth combined. There's a psychological factor where you realize that this is amazing, and in some ways absurd. It boggles the mind in a way that this would still be projectable. And when you consider that many filmmakers and many distributors saw cinema as a disposable medium — it was never intended to last this long.

Harte: The film print is a commodity that was produced to show a movie and make money. And then the film's run is over, there was no TV, there was almost no repertory rerun theaters. So these had a limited life and it's just amazing that any of them survive.

Christiano: The mentality was, "Why would you want to watch a movie again?"

Harte: And all the films that we consider classics now were not considered classics at the time they were in. They were just a movie; a good movie, maybe a not-so-good movie. All the negatives for "Casablanca" have disappeared. Just... gone. The preservation is just the best print they could find. But I worked with nitrate before I moved to Rochester 27 years ago, at Cinema Arts in a stock footage laboratory in New Jersey. And one of my jobs almost every day was taking decomposing nitrate that was just too far gone to preserve, and I would go out in the woods, take the decomp, and burn it.

When they showed me how to do it the first time, they said "make sure you don't put too much in at once." So of course the first time I did it, I put too much in. The flame was so high, I thought I was going to burn the tree branches down in front of it. But I'd pull off a section and throw the rest of the roll in the burn barrel. I'd light the section I'd ripped off with a lighter, and then I would throw the fuse into the barrel. Then I'd run like hell up the ravine, and whoosh. It doesn't explode, but once it gets going, it's going.

There's a video on Youtube called "Night of the Rocket Engine" and if you look it up, it's a superb demonstration of nitrate. And what's interesting about that is it's a 2000 foot roll sitting in its can with no top on it and no core, and it's lit from the center and you get like a 10-foot rocket engine flame. The fumes are poisonous and it'll burn until it consumes itself. It's a self-oxidizer. It creates its own oxygen as it burns, and nothing in the world can put it out.

Christiano: This might be a good time to talk about safety protocol.

Harte: We don't do that here.

Christiano: We're planning that for the fifth Nitrate Picture Show. Really go out with a bang. [laughs] But there are some safety precautions that we have to take in order to project nitrate film. And that's why only a few theaters in the world still project [the format]. One of the major precautions that we take is that we have specially equipped projectors that were designed specifically to project nitrate film. Most modern film projectors have an open film path. You can easily just look at the film path and reach in and thread it up. And our Century projectors have a film path that's fully enclosed. They have doors that open and shut, so that after you've threaded it, everything's enclosed when the projector is running. The idea is that if there were to be a nitrate emergency that would contain the fire. We have special fire rollers that would prevent any fire from traveling from the image head or the sound head up into the take-up reel or down into the rewind reel. So if there were an emergency, you would only have about six or eight feet of film burn up. And then the other 1900 feet of film would be safe.

Moving on from that, we also have a water cooling system that prevents heat from building up in the projector. We have steel shutters in front of all the port windows which are all wired together. We can release all of the shutters and have them drop simultaneously, which would prevent any fire from traveling into the audience. So the audience is safe. The projectionists, maybe not.

Tiernan: Worst case scenario, if we ever did have a fire, we're aware that we're not going to be able to put it out. So no one is reaching for the fire extinguisher to try to fight this thing. Just we're sealing up the room, we're protecting the audience, and we're getting outta there.

Christiano: Nobody's expected to go down with the ship.

Harte: We don't use the word F-I-R-E.

Christiano: We don't use the F-word.

Harte: That's where the saying about yelling fire in a crowded theater comes from. Back in the day, there were a few tragedies. We don't say that word unless it actually happens. We have a giant monkey wrench, connected to the chain that closes all the steel plates. And if there was an F-I-R-E — run for the nearest door, pull the monkey wrench. But if we don't get to pull it there's a fail-safe. So if a human didn't pull it and release it, that heat would melt the lead and down it would go.

Christiano: We also run drills. We run nitrate protection drills, where before every screening — and certainly before every Nitrate Picture Show — we talk with all the projectionists; this is our protocol, this is how we project nitrate film. And it's a little bit different because we have to be ready to stop projection at any time. So one of the reasons we have a minimum of two projectionists in the booth for every screening at the Nitrate Picture Show is because when one reel is running through one projector, that projectionist's job is to keep a hand on the dowser, so that they can close it immediately if there's any sign of an emergency, or damage, or mis-threading or anything. If they see anything amok they have their other hand over on the control panel which is ready to stop the motor and close the change-over dowser.

So if they're just watching the film as it goes through the projector, they're not watching the image on the screen. They're not paying attention to the movie. They're literally just watching the film as it goes through the projector and they're ready to jump into action at any sign of trouble. The other projectionist is monitoring the film, they're threading up their next reel, they're monitoring the image and sound. And then at the changeover those two roles switch places. Normally with a safety film screening, one person would be doing all of these jobs; with nitrate it's important that somebody is watching the film as it goes to the projector at all times so that if there were to be an emergency — if the film were to break in the projector, if a splice were to fall apart in the projector—we can stop the projection before the film ignites so that we don't have a catastrophe on our hands.

We also pre-screen all of our prints. For example, one of the films that we're showing this year, we have already shown three times in the Dryden, because we did an initial test screening to make sure that it travels safely through a projector. Also that it has that nitrate look: the portrayal of nitrate that we want to show audiences. And in this case it also needed subtitling, so we had to do some electronic subtitling tests. We have subtitling projected on a smaller screen below the main film image, because the print we have is a foreign language print and doesn't have English subtitles. We have to have our own English subtitles, and we've done two subtitling tests for that.

So everything that you'll see during the Nitrate Picture Show has already run through our projectors. It's already been painstakingly inspected.

Tiernan: You get a lot of confidence knowing that this film has gone through the projector before successfully; that this isn't the first time someone's tried to do this.

What's your mood like in the booth during the film? Do you feel tense, or is it more like a Zen state once you're actually in the process?

Jim: I think a Zen state comes close to it for me.

Tiernan: I am nervous, but my nerves are overwhelmed by my ego. [laughs] Just doing a regular screening here, you're in the major leagues of projection. And when we do the nitrate festivals, it's like the All-Star game. So I'm not going to meet many projectionists in my life who are going to have done something as amazing as that. It's something that I'm gonna brag about forever. So I am nervous, but it's also an opportunity that almost nobody gets to do.

Christiano: There's a real sense of vocation with this job. This is a job that very few people in the world still get to experience. This is not just a treat for the audience, but it's a treat for us in the booth that we're creating this kind of magic that isn't widely available anymore. For most people cinema has become, as Tarantino put it, "television in public," and we're kind of keeping what we believe is true cinema alive at the Dryden. It's more than just going to your local AMC and getting a bucket of popcorn, reclining in a seat and falling asleep halfway through "Guardians of the Galaxy." There's something more to cinema, and there's something more that these filmmakers intended, and we're trying to keep that vision alive here. I think we're stewards of the cinema experience and we're caretakers of that. We take that very seriously and we don't take that for granted. We know that it's a gift that we have this opportunity.