Heritage found

Walter Evans collects art he couldn’t find in museums

By Alex Miokovic and Heidi Nickisher[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Walter Evans says he doesn't remember going to art museums when he was growing up. At first it was because in the 1940s in the South (first Savannah, Georgia, and then Beaufort, South Carolina), African Americans weren't allowed in places like museums and galleries. Later, after moving to Connecticut, he was by then a typical teenage boy, more "into cars and such" than art. But that would change.

Evans joined the Navy after high school and was stationed in Philadelphia during the second half of his enlistment. While there, he happened to go on a date to the Philadelphia Art Museum. By the time the second date rolled around, and wanting only to impress her, he'd secretly done some reading about art and artists. But something else happened, too. Soon he was visiting other major museum collections in New York City and Washington, DC.

He began to notice, however, that in collection after collection there was no art by African Americans. Meanwhile, Evans also started reading American and Russian classics as well as African American writers like Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, and James Baldwin.

It wasn't until after Evans completed his medical residency in Detroit that he made his first art purchase: The Legend of John Brown, a portfolio of 22 silkscreen prints by Jacob Lawrence. A few weeks later, having been invited to a benefit in New York City for the dance studio of Nanette Bearden, the wife of artist Romare Bearden, he bought The Magic Garden.

These pieces were just the beginning, and by the early 1980s Evans was collecting art in earnest. He wanted a significant body of work so that his young twin daughters would grow up seeing work by African Americans --- work that, to this day, you still don't see in many museums.

The Walter O. Evans Collection of African American Art is a thoughtful presentation of a selection from an important and broad-based collection. And it's a collection put together by a passionate and erudite collector. Dr. Evans has been named one of the top 100 collectors in the country by Art and Antiques magazine. At the present time he owns more than 200 paintings, photographs, sculptures, and works on paper by 19th- and 20th-century artists. Eighty works --- ranging from Barbizon-inspired landscapes to works from the Harlem Renaissance to Cubist abstractions --- are in the traveling exhibition, now at the Memorial Art Gallery.

Two of the artists in the collection, Lawrence and Bearden, drew upon their unique cultural experiences as African Americans and combined those experiences with the formal language of Expressionism and Social Realism to create images that either evoke memories of life (Bearden) or recount black history through narrative scenes (Lawrence). The end result is a visual reward for the viewer. Throughout the exhibition, we are treated to outstanding examples of experimentation and synthesis.

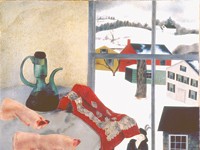

We see, for example, in Beardon's The Magic Garden (1978), the figure of a woman with a bright yellow broad-brimmed hat sitting in the foreground. She is surrounded by a variety of flowers and lush greenery. Although the image is small, it allows for a feeling of great intimacy. It is as if we've been invited to take a peek into Bearden's past --- perhaps back to those early childhood days in North Carolina and the well-tended garden of a beloved grandmother.

But what is really magical about The Magic Garden is that Bearden constructs it from images cut out from magazines. And somehow, these seemingly rough and fractured cuts, in the hands of a master, coalesce in an image that reads as a seamless scene, working its way from the foreground figure and into an amazingly believable space, and leading our eye through the garden to the house in the process. The illusion is quite incredible.

Aaron Douglas, another artist highlighted in the exhibition, used the visual language of Synthetic Cubism to symbolically represent the historical and cultural memories of African Americans. And although over 60 years separate them, he and Lawrence each created a series of works on paper that were not only based on their own personal experiences in the African American church but also were visual documents of the very important role and character of the preacher in that church.

A central part of the exhibition are Douglas's illustrations of James Weldon Johnson's book of poems interpretatively based on popular folk sermons, God's Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse (1927), such as The Creation and The Judgment Day. Also included is Lawrence's Genesis Creation Sermon series (1989), which was inspired by the powerful sermons of Reverend Adam Clayton Powell, Sr. --- a pastor at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem when Lawrence was growing up.

And these are just a few of the 20th-century artists. Although no one "taught" Evans how to collect art, he did attend various lectures and picked up collecting strategies from some dealers. One even suggested that he buy a painting by the late 18th- and early 19th-century artist Joshua Johnson. But, at the time, Evans was only interested in work with black subjects by black artists. (He passed, only to find out a few years later that Johnson's work was now out of his price range.)

What Evans soon realized, however, was that even if there were a handful of African Americans working as artists in the 19th century, for the most part, their patrons were still predominately middle- and upper-class whites who wanted either portraits or landscapes. So Evans started collecting the landscapes of Robert Scott Duncanson --- a self-taught biracial artist and a landscape painter of the Hudson River school tradition, as seen in Man Fishing (1848).

And he bought the neoclassical sculptures --- such as The Marriage of Hiawatha (1868) --- of Mary Edmonia Lewis, whose father was African American and mother was Chippewa. Duncanson was also the first African American artist to receive international recognition, while Lewis achieved national prominence as the first African American sculptor. (Of interesting local note, both were also born in upstate New York.)

Evans is forthright when talking about his collection. "If it weren't for my career, I would not have been able to collect," he says. And he is also deservedly proud of his efforts that have that resulted in such a collection. Not only does he own one of Henry Ossawa Tanner's important paintings, Florida (1894), but he and his wife were also on hand at the Clinton White House to see a Tanner painting permanently installed --- the first and only piece of African American art in the permanent White House collection.

When asked if he has favorites among his collection, Evans says he doesn't. "They're all my children... don't have favorites among my children," he says. As for why he decided to take his collection out of his home and put it on the road, he says, "nature doesn't like a vacuum."

Although he is referring more practically to the fact that he continues to actively collect and is running out of places to put things, metaphorically it is a fitting coda. Things, like plants and people, need to see the air every once in a while to live. So, let's all be inspired by this display of an important and unique cultural heritage. Long may it live.

The Walter O. Evans Collection of African American Art is on display at the Memorial Art Gallery, 500 University Avenue, through January 2. Hours: Wednesday 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., Thursday 10 a.m. to 9 p.m., Friday 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., and Sunday 12 to 5 p.m. Free to members, UR students, and children 5 and under. General admission $10, $8 seniors and students. 585-473-7720, mag.rochester.edu

Speaking of Walter O. Evans Collection Of African American Art, Memorial Art Gallery

-

Culture Vulture

Jun 15, 2023 -

Crystal Z Campbell's 'Lines of Sight' honors Tulsa and tenacity at MAG

Mar 29, 2023 -

MAG’s timely 'In Praise of Trees' is perfect for the holiday season

Dec 7, 2022 - More »

Latest in Featured story

More by Alex Miokovic

-

Larry Merrill at M. Early Gallery

Dec 6, 2006 -

"Kim Jones: A Retrospective"

Nov 29, 2006 -

"My America" at the MAG

Nov 8, 2006 - More »

More by Heidi Nickisher

-

Larry Merrill at M. Early Gallery

Dec 6, 2006 -

"Kim Jones: A Retrospective"

Nov 29, 2006 -

"My America" at the MAG

Nov 8, 2006 - More »