The writings on the wall

When it comes to graffiti and street art, policy and public opinion vary drastically

By Rebecca Rafferty @rsrafferty

[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

When WALL\THERAPY and related events started about four years ago, Rochester joined the ranks of cities who have officially embraced the street art movement. Generally, the more than 70 murals that have been created since the project began have received positive responses from the public, but there have been a couple of hiccups.

Rochester's walls have it all: a mural festival that embraces both local talent and internationally renowned artists; shallow scribbles; deep scrawls; commissioned murals for small businesses; tons of pieces by talented graffiti crews; the ever-changing graffiti gallery in the abandoned subway; hideous commercial signage; and bad buff jobs. The arts scene is expanding, but is not without tension and growing pains.

As the street art movement continues to grow, Rochester is becoming more accepting of artwork on exterior walls, but permission for artists to make their mark is privileged, and based on specific tastes. Questions remain about the difference between mark-making that appreciates or depreciates the value of the city's walls and neighborhoods, and how we arrive at those value judgments.

Permissioned commissions

WALL\THERAPY isn't art-by-committee — the artists invited to participate are given the freedom and flexibility to paint what they will on walls offered up by private building owners, such as developer and entrepreneur Dan Morgenstern of Morgenstern Group.

"Public art plays a major role in creating a sense of 'place,'" Morgenstern says. "It promotes identity, helps to define community, stimulates conversation, provokes thought, and adds 'color' to a neighborhood." Buildings are the bones we live and work in, and public art adds the flesh, he says.

Building owners with potential walls are approached by WALL\THERAPY organizers for permission to paint their property, and are shown examples of the artwork that a selected artist has previously produced, says Ian Wilson, WALL\THERAPY founder. "That is the keystone of our curatorial process: matching an artist with a potential wall and environment."

At times, an artist doesn't even decide on a composition until after arriving in Rochester and interacting with the people and environment surrounding the wall to be painted. "In that way, the creation of a WALL\THERAPY mural is far more experiential than commercial," Wilson says.

"We are also approached by property and business owners who wish to be a part of the project," says Erich Lehman, WALL\THERAPY co-organizer and lead curator. "We do focus on permission-based walls, as we want these murals to have the best chance of a long life."

Lehman says that once the walls are secured, research about the neighborhoods is conducted and the team works to curate a good match between artist, neighborhood, and the wall's physical properties.

"An artist will often be presented with a few possibilities to see what might inspire them most," he says. "Simultaneously, we present existing portfolios and bodies of work to property owners to try and show the potential of what the wall might become. These aren't proposals for the walls; they are merely examples of what is possible."

From the outset, organizers work to educate all of the participating artists about the goal of the project, and "ask that they work in a very loose set of guidelines," Lehman says. "From there, we seek to enable as much freedom as possible."

Wilson says there have been cases when more consideration was given to content. "Those instances when artists have had to create within 'loose boundaries' have arisen as the result of a conversation about the neighborhoods, history, and sensibilities," he says.

For example, the mural produced by New York City-based artist Alice Mizrachi in the Susan B. Anthony Neighborhood was born of an ongoing discussion about the history of the neighborhood, the desire for youth involvement, and the artist's practice. The property owner, Barbara Hoffman, has a specific interest in preserving and complementing the neighborhood's historic value.

"I'll take art-by-conversation over art-by-committee for as long as the Genesee River continues to run northward," Wilson says.

A total of six WALL\THERAPY murals adorn Morgenstern's buildings in the St. Paul neighborhood. The walls include works by South Africa-based artists Faith47 and DALeast, and Belgian artist ROA. Morgenstern took a risk by allowing bold, large-scale murals to be painted on his buildings without prior approval of the designs or the content of the work, but he says he's happy with the results.

"I chose to accept the approach because I believe in the artist's creative right," Morgenstern says. "I also believe that the vast majority of artists understand the wall as a canvas visible by the general community, and make responsible choices about the images based on the wall's location."

But not everyone agrees. A surprising number of people responded to ROA's mural of two sleeping bears, one piled on the other, with reactions that ranged from cheeky winks to outrage and disgust. ROA has said that his black and white large-scale paintings of animals are meant to remind us of our dubious role as a dominant species and the impact we have had on the nature we take for granted. Some Rochesterians see something lurid.

"Everybody feels like it looks like two rodents in a sexual act," says Jack Wolsky, whose St. Paul loft has a front-row view of ROA's mural.

"We have three windows facing that mural, and every morning my wife insists on the shades being closed so we don't have to look at it," he says. "It's directly impacted our daily living because it's directly out of our window."

Wolsky says his negative stance on the mural is "kind of ironic, because I'm an artist, I've taught art, and I'm for freedom of expression, but this thing is so out of place and out of context; it's almost like a joke."

He says the underlying problem is the fact that it was put up in such a visible place without what he considered to be an appropriate approval process. "I think there was good intentions involved," he says. "I'm not saying it was done intentionally to do any harm. I just think there was poor planning, and not enough input by other sources."

Wolsky has served on committees for public art installations, including the group that selected the work for the Rochester International Airport, which had representatives from all walks of life. "We had educators, museum people, business people. We went over it for two years to decide what would be appropriate for the airport, and as a result, I think we did a good job," he says.

While ROA's "Bears" painting received the most publicity, Faith47's bare-breasted female image on the Michael Stern building facing the Victory Church received the most back-room pressure, Morgenstern says.

"The 'Bears' were more fun — as large numbers of people watched ROA paint it," and interacted with one another, he says.

But he says that Faith47's piece "drew an angry, vitriolic response from a religious community." The group felt it was being subjected to "evil" imagery and went to the city and political avenues for relief.

In the cases of both murals, city officials responded by stating that because the buildings were privately owned, there would not be an effort to remove them.

The tension has mostly settled, Morgenstern says, with the occasional comment still cropping up, but he is undeterred by the controversy. "Actually the conversation our murals have stimulated have in fact brought us Warhol's '15 minutes of fame,'" he says.

This attention serves a greater purpose: "We have seen interaction by neighbors who have rarely, if ever, spoken to each other," Morgenstern says. "The murals have helped to identify our neighborhood and buildings, which we now hear others in Rochester referring to." The buzz brings value to the properties, and that promotion "moves the needle with regard to uplifting a once very depressed and forgotten part of our downtown."

Vandalism, art, and where the lines are drawn

More recently, two WALL\THERAPY murals — one by Rochester-based artist St. Monci, and another by London-based, Irish artist, Conor Harrington — were marked up with red paint by an unknown vandal. It's uncertain if this was a statement of disapproval or just a random act.

"Art painted with permission in the public space is still subject to vandalism, as is any structure accessible to the public," Ian Wilson says. "Both of the artists have roots in a culture that treats the ephemeral nature of the artwork as an acceptable consequence."

Part of another WALL\THERAPY commission, "The Trying," by Israeli artist Know Hope, was buffed — painted over with neutral colors — with some speculation from the community that it might have been mistaken for illegal graffiti by the City of Rochester's Defacer Eraser graffiti removal team.

"The lettering was buffed while the character illustration was left intact," Wilson says. "If such action was the result of a group sanctioned by this city, I suggest more diligence be done before deciding that lettering on a wall is a 'tag.' Individuals authorized by committees are apt to make such value judgments."

To someone not educated or informed about a given artist's work, all scrawlings on a wall look the same, Lehman says.

This is particularly problematic if Rochester and organizations like WALL\THERAPY want to embrace not only street artists, but artists with deep roots in graffiti culture. The city has murals created by graffiti artists from near and far, including Bones and Range, two members of Rochester's oldest graffiti crew, FUA Krew. Members of FUA have been painting Rochester's walls for 25 years, and some of the individual members have been at it longer than that.

Though not every wall that FUA paints is legal — many of the spots that the crew claims began without permission, and their presence gradually became accepted — Range says that some communities not only accept the graffiti, but happily anticipate it.

In particular, North Clinton Avenue — where FUA hosts the annual BBOY BBQ graffiti and hip-hop event — embraces graffiti. "People look forward to it, to what's going to be the new theme, now that we've evolved into bigger productions," he says.

Range argues that in some cases, graffiti can be considered a neighborhood-improvement service, and that complaints that what his crew does isn't art comes from a population from outside of the neighborhood who misunderstand what they're seeing.

"To me it's kind of biased," he says. "You don't even live there. And the people I walk past every day, they love it. They're the people that live there."

The crew is paying out-of-pocket to transform a depressed area, Range says. "We roll up the walls, we scrape the walls of these abandoned buildings, and we hook them up," not the naysayers, Range says. The city "can fix these walls in a heartbeat, in a minute, but they don't. And now you want to complain about the content that we put on this wall?"

But of course there's a spectrum. Range says he digs anything artistic being put up, but hates to see "mediocre tags in the wrong places." This includes people tagging outside of established graffiti spots, like in public areas around the abandoned subway.

"It's a lack of respect for the painting area, for that spot," he says. "People are tagging around it, when you clearly have more than a mile's worth of walls to paint, and you still want to go out and tag near the Blue Cross Arena and risk this spot getting shut down because of your ignorance."

Range explains there is a difference between a crew establishing a new spot, putting good work in to make it an accepted place to paint, and random people tagging wherever they want. Part of it is being wise enough to know what limits to push, and what areas to respect.

"Respect is the main thing," he says. "Growing up in the ghetto, that's one of the main things you have to learn: to respect and get respected."

Everyone starts out "toy," or amateur, Range says, but the goal is to work to become a respected artist or part of a respected crew.

"That's where we're at," he says. "We have our designated walls, and even though some of them are not technically, legitimately permissioned walls, no one else is going to come and paint there without our permission. Because they have to respect the fact that we've earned the right to paint that spot."

There are many ways to follow street art and graffiti in Rochester on social media, but one particular Instagram account covers the spectrum. The person behind the @lobbyist handle captures a cross section of graffiti, street art, advertisements, and other interesting bits that hit Rochester's public walls.

Graffiti writers don't write forever — there are writers who have moved, died, or retired — and @lobbyist has a documentarian quality of capturing art that is here now, but ephemeral in nature.

"It's kind of a time capsule of what Rochester has going on in any given time," @lobbyist says. "If you look at a lot of the accomplished mural artists in the world, part of them got their start doing tags that a lot of people probably thought were crappy. They got better. This is kind of like having someone's rookie card, on some level."

Not everything he documents is pretty or impressive, but @lobbyist says the aim is to facilitate discussion.

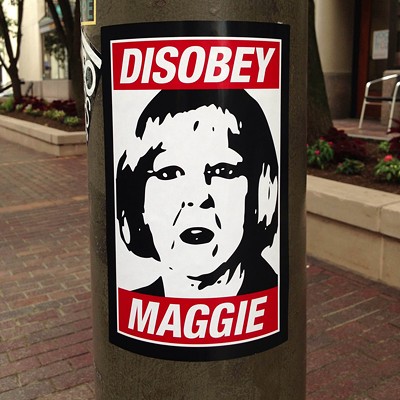

FRANK BACON is arguably one of the most enigmatic graffiti artist currently hitting Rochester's walls, and has received a lot of criticism for tagging small businesses on the nicer side of town, in addition to corporate walls and abandoned buildings.

But others just hate FRANK for bombing the city with what some consider to be unskilled tags. FRANK describes those as based on "the subway tags that were so prevalent in New York City during the 1970's and 80's. It's my way of paying homage to those brave artistic souls that started this billion dollar worldwide movement," FRANK says. "Why be fancy? Why be realistic? Why put forth so much effort? There are people far more talented and qualified than myself to do such things."

There's speculation over whether FRANK sucks, or if it's some form of Dadaism, @lobbyist says. "Conversation is so important for our community. Technically accomplished artists are great too, but if they don't get anyone to say anything other than 'gee, that looks nice,' there's kind of a banality to it."

When asked if anything was off-limits for tagging, FRANK offered three rules: "1. Do not tag any religious institutions (unless asked), automobiles (unless asked), private residences (unless asked) or people (unless asked). 2. If you decide to be rude enough to go over another writer's work you are making a statement that you can and will beat up the vandalized vandal if and when you see him or her. It's best not to go over any other writer's work (unless asked). 3. Don't get caught (unless asked)."

FRANK has also been known to make a game of putting up quoted lines from movies, without credit except for the FRANK tag. "People are always saying movie quotes and if you're not savvy enough to know which movie the quote is from, it sounds like they're making it up," FRANK says. "I took the next logical step and threw it on a wall. Because, as everyone knows, I coulda had class. I coulda been a contender. I could've been somebody, instead of a bum, which is what I am."

Bombing campaign

Just as there's a spectrum in graffiti, there's a spectrum in buffing graffiti. There's the innocent side of removing graffiti from buildings that owners don't want marked up, but there's a more insidious side, too, @lobbyist says.

To spend taxpayer money removing graffiti from a building that is at maximum eyesore level — like the half-demolished Genesee Hospital — is ridiculous and offensive, he says.

"As someone born in that hospital, I think it's bad enough they're tearing it down," @lobbyist says. "But to let it linger in this state that looks like a war-torn country for years ... I was excited that it started to look a little more beautiful with the addition of more and more graffiti. But to blow funds that could no doubt be used much more effectively elsewhere on painting a building slated for demolition with beige rectangles is asinine."

He sees compulsory graffiti removal as a problem, and believes that building owners should be able to opt out of mandatory buffing.

The City of Rochester has a mandatory graffiti removal policy, unless the building owner has submitted written consent in advance, registered that consent with the city, and had the submission approved, says Karen St. Aubin, Director of the Bureau of Operations & Parks.

If no approved consent is on record, the city will issue a notice for removal to the property owner. Failure to remove the graffiti will result in the removal by the city's buffing service, Defacer Eraser.

The Defacer Eraser service will remove graffiti from the first floor of any property once per year, St. Aubin says. Beyond that, the building owner will be billed for the removal service.

"It's a matter of taste," @lobbyist says. On one side, you have people painting script, and on the other side you have the city covering the script with beige or gray rectangles that don't match the building color. "I think it's completely subjective which makes the building look nicer," he says.

A little bit of history: In the 1970's, New York City mayor Ed Koch vowed to get rid of graffiti. "He declared a war, despite the fact that there were much more pressing issues affecting the city — despite the fact that the city went bankrupt," @lobbyist says.

The beige rectangles of today are there because policy makers have been fed this "broken window theory," he says. The theory upholds the idea that just like a broken window not getting replaced, the lingering presence of graffiti sends a message that there's no vigilance in the neighborhood and is an area where illegal activity can take place.

"I think that's an outdated theory," @lobbyist says. "It's like thinking that everyone with a tattoo is a criminal. That used to be the prevailing thought in society, and now having a sleeve of tattoos is perhaps a mark of privilege more than a sign of criminality."

So this theory takes for granted the idea that no one wants the graffiti, that it's aesthetically worthless. "People understand graffiti culture better now" @lobbyist says. "And to assume that graffiti would only be left on a wall due to absentee landlords or neglect takes out of the equation the fact that perhaps people like it and want it to be there, and in some cases, commission it."

Graffiti is a world-wide phenomenon, and those who follow the movement know that cities have particular styles, which enthusiasts travel to experience. And in some more progressive art cities, it's embraced. Berlin is covered. For a while, Barcelona became a world-wide destination for graffiti and street artists, which provided a boost to its economy in the midst of economic difficulties.

The streets are filled with imagery. There's a lot of commercial signage that is poorly designed and uninspired, and we are inundated with the marketing of arguably harmful products and ideas. (One of the reasons that WALL\THERAPY was founded was to give city youth something a bit more inspiring and uplifting to look at.)

The issue also begs the question about what it really means to be a successful arts city, and of policy makers not fully understanding the next generation of Rochesterians. This city has well-known issues with young people leaving and with economic hardships, and these grassroots, increasingly-not-fringe art movements not only cost the city no money, but are bringing young people to visit, as has been demonstrated by events put on by WALL\THERAPY and FUA Krew alike.

The graffiti policy "sends a message that our leadership doesn't have our back, so maybe we shouldn't stay here," @lobbysist says. "I think there should be a little bit more respect and consideration for the artists in Rochester, because if we all leave, this place is gonna be f***ed."

Speaking of...

-

The ultimate guide to the 2022 festival season

May 2, 2022 -

Take a post-feast street art stroll

Nov 25, 2021 -

Wall\Therapy's decade of rallying Rochester around murals

Jul 30, 2021 - More »

Latest in Art

More by Rebecca Rafferty

-

Beyond folklore

Apr 4, 2024 -

Partnership perks: Public Provisions @ Flour City Bread

Feb 24, 2024 -

Raison d’Art

Feb 19, 2024 - More »