[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

It is hard to miss Fee Brothers on Portland Avenue. Its bright yellow signage juts out boldly from the face of an unassuming brick building, adorned with its time-honored slogan: “Don’t Squeeze. Use Fee’s.”

Fee Brothers, a purveyor of cocktail syrups, cordials, and, most notably, bitters, is one of Rochester’s oldest businesses, having opened its doors on March 5, 1864 — and among the longest family-owned enterprises.

The tradition continues with the recent takeover of the company by Jon Spacher and Benn Fee Spacher, brothers who recently purchased the company for an undisclosed price from their aunt, Ellen Fee, who, with her late brother, Joe Fee, cemented Fee Brothers’ reputation as a global powerhouse of cocktail mixers.

“We’re a family-owned company, and we take a lot of pride in that, obviously, and what we want to keep doing is just turning out a good product and getting the good word out to as many people in the world as we can,” Jon Spacher said.

Joe died last year at the age of 55, and Ellen, after 42 years in the industry, was ready for a break. Spacher steps in as chief executive officer, and Fee Spacher is the chief operations officer.

“This was like two weeks after Joe died, when the two of them said they were interested, it was like the clouds parted and the angels sang,” Ellen Fee said.

A FAMILY AFFAIR

Some of the fondest memories Benn, 34, says he has of his childhood are at the company’s cocktail mix factory.

Back then, conveyor belts dipped, dived, and zipped throughout the facility and doubled as an after-hours playground. Fee Spacher recalls sitting on a plywood sheet and riding the belts like a roller coaster.

“One of my best memories as a kid was Ellen coming up to me and saying, ‘See this board? See this maze of conveyor belts?’” Benn said. “She said, ‘You’re going to be crying by the end of this, but it’s going to be fun. You will pinch your fingers, and it will hurt.’”

It was the same childhood Ellen experienced and with the same caveats — don’t tell Mom if you skin your arm on the belt because the amusement park will be shut down.

In Ellen’s day, Fee Brothers was run by her parents Margaret and Jack Fee. Jack, who also worked as a chemist at Eastman Kodak, is credited with innovating a wealth of new flavors to the Fee Brothers roster. Today, the company offers 98 products, including 19 types of bitters.

Ellen’s brother, Joe, meanwhile, became an iconic figure for Fee Brothers as a traveling salesman. At 6 feet, 5 inches tall, he wore an Akubra hat like Crocodile Dundee, and trotted the globe to cocktail conventions and bars hawking bitters to anyone willing to take a nip.

The result was that, for a time, Fee Brothers was on every continent besides Antarctica. That wasn’t for want of trying.

“Joe went to Antarctica, with the bitters in his pocket, and never made it to even a laboratory bar,” Ellen said. “He wanted to put just one bottle down in Antarctica, and it didn’t happen.”

While 88 percent of Fee Brothers’ sales continue to be based in the United States, the company has seen a global spike in demand. Australia, in particular, has become a hot market, according to the company.

To take up the mantle at Fee Brothers, Jon and Benn left behind established careers. Jon, 44, was regional president for Main Street America Insurance. Benn was an information technology security administrator.

The brothers broke with tradition somewhat in becoming the first descendants to buy the company outright without first having had significant experience on the inside. Jon explained that previous generations, including Ellen and Joe, worked at Fee Brothers for decades before taking the helm, and earned shares of the company piecemeal through “sweat equity” before becoming full owners.

While Ellen dreaded the thought of selling the business over to someone outside the family, Jon and Benn said they never felt any pressure to take over the business. They said maintaining the legacy was not on their minds when they bought in.

“This wasn’t about keeping the fifth generation going,” Jon said. “This was about, ‘Okay, how can we help Ellen?’”

Ellen, 63, said she intends to stick around through 2021 to ensure a smooth transition. And then?

“I’m going to get an RV, and I’m going to travel the United States every summer until I can’t travel the United States every summer anymore,” Fee said.

TURNING PRIESTS INTO BOOTLEGGERS

The Fee Brothers we know today started in earnest as an importer of liquors and was founded by four brothers — John, James, Owen, and Jacob Fee — who stumbled into the business after trying their hands at running a tavern and deli.

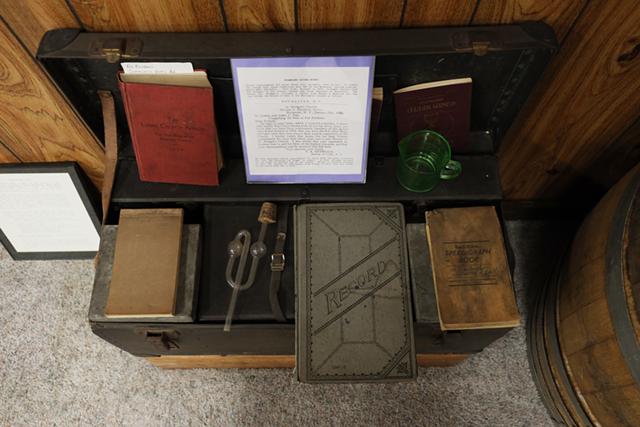

British gins, Jamaican rums, and French cognacs all flowed through what they called “The Largest Wine and Liquor House in America,” first on St. Paul Boulevard and, later, on North Water Street. A yellowed copy of the original lease for the North Water Street facility sits in a frame on the wall of the company’s “museum room.”

In the 1880s, the Fee Brothers took a turn at producing its own wine from the Genesee Valley Vineyard and Winery, a venture that would quickly become the nexus of the business.

“There’s a story that’s told, this is at [the old plant on] Water Street, the guy next door wanted free wine, and my grandfather wouldn’t give him free wine, so he went into his basement and he drilled a hole through and put a pipe into one of our barrels so he could get free wine,” Ellen said. “The joke’s on him, because the truth is, the wine was brand new, it hadn’t fermented yet. All he would’ve gotten was a stomach ache.”

When Prohibition hit in 1920, Fee Brothers did not go quietly into the night. The sale of wine, of course, was illegal, but a glaring loophole existed behind the pulpit. Sacramental, or “altar wines,” were already a business for Fee Brothers, but, as company lore has it, sales shot up 700 percent during Prohibition.

Churches were legally allowed to scoop up the wines, with a choice of 12 varieties for the discerning parishioner, ranging from port to Chateau Blanc. The story goes that worshippers in some parishes could walk away with a case of Fee Brothers vino in exchange for a healthy donation.

“We were turning priests into bootleggers,” Ellen said with a laugh.

Throughout Prohibition, Fee Brothers jumped through loopholes to meet demand. The company created “Bruin,” a malt extract sold with a detailed warning list of what awful things you should never do to turn the syrup into beer.

Then there was the home winemaking service. Under Prohibition, the head of a household could make up to 200 gallons of wine per year. Fee Brothers seized on that opportunity, offering loaded vats of grape concentrate known as “Vin-Glo” to households and to return to bottle it up after the juice fermented.

The company still has a leger bearing some of the names of people who indulged in the service. Among them were the University of Rochester President Rush Rhees and the city’s fire chief, William Creegan.

“There were also an awful lot of restaurants, too, or rather, restaurant owners,” Ellen said. “And then next to the restaurant owners you had their neighbors, and they used that so they could get the wine from their neighbors, too, and put it in the restaurants.”

Those Prohibition tricks were not only classic examples of ingenuity during the Noble Experiment, but also what led Fee Brothers to shift into manufacturing bitters — or flavoring. Not to put too fine a point on it, but gin made in a bathtub isn’t likely to win any awards without flavoring.

“My grandfather would say, ‘Here’s some peppermint extract, here’s some green food coloring, add some sugar, add your bathtub gin, and you’ve got crème de menthe,’” Ellen said. “That’s when he had this lightbulb moment where he thought, ‘I could be making these syrups.’”

The wine business for Fee Brothers had receded by the middle of the last century, according to company lore, when the then-owner John Fee II decided to focus on the non-alcoholic products that were gaining in popularity. After he died in 1951, his wife, Blanche Fee, seeking to honor his wishes, contacted the State Liquor Authority to rescind their licenses.

When liquor authority agents arrived to account for the leftover inventory, they were said to have busted the barrels open with hatchets and dumped the wine into the Genesee River.

“You’d think they could have at least given us some time to sell off what was left,” Fee said.

And as the Genesee briefly was tinted burgundy, Fee Brothers was officially all in on the syrups and bitters business.

A NEW WAVE OF SUCCESS

Today, the company’s influence in the spirits world has reached the apex of society.

The White House, at its Christmas party in 2009, offered a “Stone Fence” cocktail was on the menu, made with applejack, apple cider, mint, and a dash of Fee Brothers aromatic bitters.

Fee Brothers’ success was also bolstered in the mid-2000s, when Angostura, the Trinidadian company credited with originating bitters, temporarily stopped production and redirected sales to Rochester.

Business has been good lately, according to the company. Jon said sales have grown by double digits for the past five years or so, a growth fueled in part by the renewed interest in craft cocktails and the pandemic.

“Everybody’s been home, everybody’s been doing these master classes online for all sorts of different things,” Jon said. “But one of the areas that has really exploded are master classes online for mixology.”

Where Fee Brothers stands as a business is fairly ideal for new leadership. The machine is well lubricated. The facility boasts a modest staff of 10 people, and each label is still affixed to bottles by hand, some by workers provided by the Arc of Monroe, a nonprofit that assists people with developmental disabilities. Much of the equipment remains unchanged since 1964, when the company moved into the Portland Avenue facility.

“It’s a lot of humility, a lot of gratitude, and a little bit of pressure,” Jon said. “We recognize that we’re coming into this, and such a great name has already been built.”

Gino Fanelli is a CITY staff writer. He can be reached at (585) 775-9692 or [email protected].

Fee Brothers, a purveyor of cocktail syrups, cordials, and, most notably, bitters, is one of Rochester’s oldest businesses, having opened its doors on March 5, 1864 — and among the longest family-owned enterprises.

The tradition continues with the recent takeover of the company by Jon Spacher and Benn Fee Spacher, brothers who recently purchased the company for an undisclosed price from their aunt, Ellen Fee, who, with her late brother, Joe Fee, cemented Fee Brothers’ reputation as a global powerhouse of cocktail mixers.

“We’re a family-owned company, and we take a lot of pride in that, obviously, and what we want to keep doing is just turning out a good product and getting the good word out to as many people in the world as we can,” Jon Spacher said.

Joe died last year at the age of 55, and Ellen, after 42 years in the industry, was ready for a break. Spacher steps in as chief executive officer, and Fee Spacher is the chief operations officer.

“This was like two weeks after Joe died, when the two of them said they were interested, it was like the clouds parted and the angels sang,” Ellen Fee said.

A FAMILY AFFAIR

Some of the fondest memories Benn, 34, says he has of his childhood are at the company’s cocktail mix factory.

Back then, conveyor belts dipped, dived, and zipped throughout the facility and doubled as an after-hours playground. Fee Spacher recalls sitting on a plywood sheet and riding the belts like a roller coaster.

“One of my best memories as a kid was Ellen coming up to me and saying, ‘See this board? See this maze of conveyor belts?’” Benn said. “She said, ‘You’re going to be crying by the end of this, but it’s going to be fun. You will pinch your fingers, and it will hurt.’”

It was the same childhood Ellen experienced and with the same caveats — don’t tell Mom if you skin your arm on the belt because the amusement park will be shut down.

In Ellen’s day, Fee Brothers was run by her parents Margaret and Jack Fee. Jack, who also worked as a chemist at Eastman Kodak, is credited with innovating a wealth of new flavors to the Fee Brothers roster. Today, the company offers 98 products, including 19 types of bitters.

Ellen’s brother, Joe, meanwhile, became an iconic figure for Fee Brothers as a traveling salesman. At 6 feet, 5 inches tall, he wore an Akubra hat like Crocodile Dundee, and trotted the globe to cocktail conventions and bars hawking bitters to anyone willing to take a nip.

The result was that, for a time, Fee Brothers was on every continent besides Antarctica. That wasn’t for want of trying.

“Joe went to Antarctica, with the bitters in his pocket, and never made it to even a laboratory bar,” Ellen said. “He wanted to put just one bottle down in Antarctica, and it didn’t happen.”

While 88 percent of Fee Brothers’ sales continue to be based in the United States, the company has seen a global spike in demand. Australia, in particular, has become a hot market, according to the company.

To take up the mantle at Fee Brothers, Jon and Benn left behind established careers. Jon, 44, was regional president for Main Street America Insurance. Benn was an information technology security administrator.

The brothers broke with tradition somewhat in becoming the first descendants to buy the company outright without first having had significant experience on the inside. Jon explained that previous generations, including Ellen and Joe, worked at Fee Brothers for decades before taking the helm, and earned shares of the company piecemeal through “sweat equity” before becoming full owners.

While Ellen dreaded the thought of selling the business over to someone outside the family, Jon and Benn said they never felt any pressure to take over the business. They said maintaining the legacy was not on their minds when they bought in.

“This wasn’t about keeping the fifth generation going,” Jon said. “This was about, ‘Okay, how can we help Ellen?’”

Ellen, 63, said she intends to stick around through 2021 to ensure a smooth transition. And then?

“I’m going to get an RV, and I’m going to travel the United States every summer until I can’t travel the United States every summer anymore,” Fee said.

TURNING PRIESTS INTO BOOTLEGGERS

The Fee Brothers we know today started in earnest as an importer of liquors and was founded by four brothers — John, James, Owen, and Jacob Fee — who stumbled into the business after trying their hands at running a tavern and deli.

British gins, Jamaican rums, and French cognacs all flowed through what they called “The Largest Wine and Liquor House in America,” first on St. Paul Boulevard and, later, on North Water Street. A yellowed copy of the original lease for the North Water Street facility sits in a frame on the wall of the company’s “museum room.”

In the 1880s, the Fee Brothers took a turn at producing its own wine from the Genesee Valley Vineyard and Winery, a venture that would quickly become the nexus of the business.

“There’s a story that’s told, this is at [the old plant on] Water Street, the guy next door wanted free wine, and my grandfather wouldn’t give him free wine, so he went into his basement and he drilled a hole through and put a pipe into one of our barrels so he could get free wine,” Ellen said. “The joke’s on him, because the truth is, the wine was brand new, it hadn’t fermented yet. All he would’ve gotten was a stomach ache.”

When Prohibition hit in 1920, Fee Brothers did not go quietly into the night. The sale of wine, of course, was illegal, but a glaring loophole existed behind the pulpit. Sacramental, or “altar wines,” were already a business for Fee Brothers, but, as company lore has it, sales shot up 700 percent during Prohibition.

Churches were legally allowed to scoop up the wines, with a choice of 12 varieties for the discerning parishioner, ranging from port to Chateau Blanc. The story goes that worshippers in some parishes could walk away with a case of Fee Brothers vino in exchange for a healthy donation.

“We were turning priests into bootleggers,” Ellen said with a laugh.

Throughout Prohibition, Fee Brothers jumped through loopholes to meet demand. The company created “Bruin,” a malt extract sold with a detailed warning list of what awful things you should never do to turn the syrup into beer.

Then there was the home winemaking service. Under Prohibition, the head of a household could make up to 200 gallons of wine per year. Fee Brothers seized on that opportunity, offering loaded vats of grape concentrate known as “Vin-Glo” to households and to return to bottle it up after the juice fermented.

The company still has a leger bearing some of the names of people who indulged in the service. Among them were the University of Rochester President Rush Rhees and the city’s fire chief, William Creegan.

“There were also an awful lot of restaurants, too, or rather, restaurant owners,” Ellen said. “And then next to the restaurant owners you had their neighbors, and they used that so they could get the wine from their neighbors, too, and put it in the restaurants.”

Those Prohibition tricks were not only classic examples of ingenuity during the Noble Experiment, but also what led Fee Brothers to shift into manufacturing bitters — or flavoring. Not to put too fine a point on it, but gin made in a bathtub isn’t likely to win any awards without flavoring.

“My grandfather would say, ‘Here’s some peppermint extract, here’s some green food coloring, add some sugar, add your bathtub gin, and you’ve got crème de menthe,’” Ellen said. “That’s when he had this lightbulb moment where he thought, ‘I could be making these syrups.’”

The wine business for Fee Brothers had receded by the middle of the last century, according to company lore, when the then-owner John Fee II decided to focus on the non-alcoholic products that were gaining in popularity. After he died in 1951, his wife, Blanche Fee, seeking to honor his wishes, contacted the State Liquor Authority to rescind their licenses.

When liquor authority agents arrived to account for the leftover inventory, they were said to have busted the barrels open with hatchets and dumped the wine into the Genesee River.

“You’d think they could have at least given us some time to sell off what was left,” Fee said.

And as the Genesee briefly was tinted burgundy, Fee Brothers was officially all in on the syrups and bitters business.

A NEW WAVE OF SUCCESS

Today, the company’s influence in the spirits world has reached the apex of society.

The White House, at its Christmas party in 2009, offered a “Stone Fence” cocktail was on the menu, made with applejack, apple cider, mint, and a dash of Fee Brothers aromatic bitters.

Fee Brothers’ success was also bolstered in the mid-2000s, when Angostura, the Trinidadian company credited with originating bitters, temporarily stopped production and redirected sales to Rochester.

Business has been good lately, according to the company. Jon said sales have grown by double digits for the past five years or so, a growth fueled in part by the renewed interest in craft cocktails and the pandemic.

“Everybody’s been home, everybody’s been doing these master classes online for all sorts of different things,” Jon said. “But one of the areas that has really exploded are master classes online for mixology.”

Where Fee Brothers stands as a business is fairly ideal for new leadership. The machine is well lubricated. The facility boasts a modest staff of 10 people, and each label is still affixed to bottles by hand, some by workers provided by the Arc of Monroe, a nonprofit that assists people with developmental disabilities. Much of the equipment remains unchanged since 1964, when the company moved into the Portland Avenue facility.

“It’s a lot of humility, a lot of gratitude, and a little bit of pressure,” Jon said. “We recognize that we’re coming into this, and such a great name has already been built.”

Gino Fanelli is a CITY staff writer. He can be reached at (585) 775-9692 or [email protected].

Latest in Restaurant News

More by Gino Fanelli

-

DeWolf Brewing Company set to open in Victor

Apr 26, 2024 -

These small cannabis farmers say New York's legal weed rollout is ruining their lives

Mar 21, 2024 -

Man shakes fist at sun

Mar 15, 2024 - More »