[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Among the assortment of citations crowding the walls of Dr. Michael Mendoza’s office, there isn’t one for his bedside manner. But to hear him speak, it isn’t a stretch to imagine his temperament received some recognition at some point in his career.

Even when he’s inundated, which is often these days, his voice rarely registers above the calming pitch you might hear on a smooth jazz radio station in the middle of the night — deadpan but reassuring.

That voice has come in handy in his role as the Monroe County health commissioner and de facto local public face of scientific guidance on the pandemic, a duty that requires an around-the-clock availability and vigilance.

“You know,” he said flatly, “I was thinking as I was walking down here that it’s already been a long week.” It was just after 9 o’clock on a Monday morning.

Mendoza was shoe-horning in a socially-distanced interview with me between a call with county leaders and employee evaluations he had yet to conduct, the latter a stark reminder that the mundanity of management persists even in a pandemic.

The previous weekend had seen almost 1,200 new cases of COVID-19 in the county. The next day, Mendoza would introduce the logistics of the state’s plan to administer the first 50,000 doses of a vaccine locally, an effort that he called “the largest public health undertaking of our generation.”

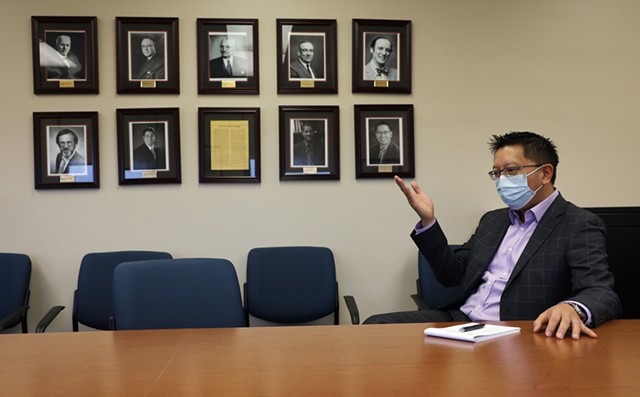

He sat masked in a colorless conference room a few paces from his office on the ninth floor of the county Health Department building on Westfall Road against a backdrop of portraits of his predecessors, who, despite their contributions to public health, few people could name.

A modicum of anonymity usually accompanies public service work, even the relatively prominent role of health commissioner. With the exception of police chiefs, the heads of local government agencies tend to be largely invisible to the public, trotted out for the occasional news conference while doing most of their business behind closed doors.

But Mendoza, 46, has been omnipresent during the health crisis, cutting a high and sometimes contentious profile, earning himself both high praise and scorn for his handling of the situation.

For a few months, the Finger Lakes region was hailed statewide for its vigilance in stopping the spread of the virus. The National Association of City and County Health Officials recognized the county Health Department as a “Promising Practice” of 2020. Donuts Delite put Mendoza’s face on a doughnut and couldn’t keep up with demand.

When Mendoza sat down in that conference room, the region had the dubious distinction of having the highest positivity rate in the state. A few days later, the county would hit a new record high of daily cases, followed by another record the next day.

Asked whether he was living a dream or a nightmare, Mendoza replied, “Neither. It’s my job.”

That job has morphed into something distinct from anything anyone in his position experienced before.

His office, for instance, has become a makeshift television studio, equipped with LED lighting to enhance the video news briefings he conducts almost daily.

Behind the door, a giant white board on the wall is a Cartesian coordinate graph that Mendoza drew early in the pandemic to map the spread of the virus. With “Contact Intensity = Distance x Duration” on the X axis and “Risk = Number x Demographic” on the Y, car washes pose the lowest risk of contraction.

A Dr. Anthony Fauci bobble-head doll stands sentry on his desk. “There’s a Michael Mendoza bobble-head doll on the way,” he said in all seriousness. What other Monroe County health commissioner has been a bobble-head?

To some extent, every local health commissioner in the country fell into their newfound role of pandemic posterchild. Few have experience with pandemics.

More so than most, though, Mendoza fell into his.

He had half-heartedly applied for the position when he was appointed by County Executive Cheryl Dinolfo on an interim basis in 2016. As he recalled, he wrote two words in the section of the online application reserved for a cover letter: “Call me.”

“I was very neutral about the job,” Mendoza said. “I wasn’t looking for a job. I wasn’t unhappy with my job.”

At the time, Mendoza was the medical director of Highland Family Medicine, one of the largest family medicine practices in the country, and the commissioner position had become something of a revolving door.

Mendoza became the second interim commissioner in as many years. The previous permanent commissioner, a posting that is to be a six-year term, lasted two years before taking a similar job out of town. The situation got to the point that the state chastised the county for being unable to hold on to a full-time commissioner. County officials claimed no one wanted the job.

He was encouraged to apply by Dr. Jeremy Cushman, who preceded Mendoza as interim commissioner. As Cushman saw it, Mendoza had the pedigree — he holds master’s degrees in public health and business administration — and the temperament.

Mendoza agreed to a full-term appointment in 2017 on the condition that he could continue seeing patients, which he does two days a week. His term expires in early 2023 and he said he intends to serve it out and get re-appointed.

“Let’s face it, Dr. Mendoza is a very effective communicator,” Cushman said. “And yes, he’s a great physician and a great leader of that department. But he is an extremely effective communicator and that’s what we need right now.”

Two days after we talked, Mendoza tweeted a photo of himself being administered the vaccine at Highland Hospital. Then he took the time to answer replies from followers, including a vaccine skeptic.

One regret Mendoza has about his handling of the pandemic is being slow to promote the widespread use of masks. Recall that early in the pandemic the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sent the mixed message that masks do not slow the spread of the virus but should be conserved for healthcare workers.

“I think I had the same feeling that most people had, which was, ‘Shouldn’t any mask be better than no mask?’” Mendoza said. “I wish I had had the confidence in my role to go against the CDC. That’s what it would’ve been at that time. And certainly I would have caught heat for that.”

Mendoza grew up one of two children in the Chicago suburb of Downers Grove. His parents, Filipino immigrants, divorced as he was finishing the third grade and he and his sister were raised by their mother.

She worked at Argonne National Laboratory operated by the University of Chicago, which made Mendoza eligible for a scholarship to the school. He studied environmental science as an undergraduate and attended medical school there.

He completed his residency at the University of California–San Francisco and spent four years practicing family medicine in Chicago before moving to Rochester in 2009. He and his wife, Dr. Lisa Vargish, and their two children, ages 15 and 12, live in Brighton.

There are many casualties of the pandemic, but one of them for Mendoza is the time he has lost with his children.

“I’ve always said, ‘I wanted to be the father I never had,’” Mendoza said. “The casualty of this job for me is that I will probably have missed a good year of time with my kids. I’ve got 12-to-14-hour days every day, I mean, I’m barely there.

“That’s time you never get back,” he added. “That’s the hardest part.”

Back in his office, as I scoured the citations on his wall, he pointed to the one he said was most important to him. “Did you see my ‘M.D.’?” he asked.

It was a framed poem from his children titled, “My Daddy, MD.”

CORRECTION 1.4.21: This article has been updated from its original version to correct a misspelling of the name of Dr. Michael Mendoza's wife. She is Dr. Lisa Vargish.

David Andreatta is CITY's editor. He can be reached at [email protected].

Even when he’s inundated, which is often these days, his voice rarely registers above the calming pitch you might hear on a smooth jazz radio station in the middle of the night — deadpan but reassuring.

That voice has come in handy in his role as the Monroe County health commissioner and de facto local public face of scientific guidance on the pandemic, a duty that requires an around-the-clock availability and vigilance.

“You know,” he said flatly, “I was thinking as I was walking down here that it’s already been a long week.” It was just after 9 o’clock on a Monday morning.

Mendoza was shoe-horning in a socially-distanced interview with me between a call with county leaders and employee evaluations he had yet to conduct, the latter a stark reminder that the mundanity of management persists even in a pandemic.

The previous weekend had seen almost 1,200 new cases of COVID-19 in the county. The next day, Mendoza would introduce the logistics of the state’s plan to administer the first 50,000 doses of a vaccine locally, an effort that he called “the largest public health undertaking of our generation.”

He sat masked in a colorless conference room a few paces from his office on the ninth floor of the county Health Department building on Westfall Road against a backdrop of portraits of his predecessors, who, despite their contributions to public health, few people could name.

A modicum of anonymity usually accompanies public service work, even the relatively prominent role of health commissioner. With the exception of police chiefs, the heads of local government agencies tend to be largely invisible to the public, trotted out for the occasional news conference while doing most of their business behind closed doors.

But Mendoza, 46, has been omnipresent during the health crisis, cutting a high and sometimes contentious profile, earning himself both high praise and scorn for his handling of the situation.

For a few months, the Finger Lakes region was hailed statewide for its vigilance in stopping the spread of the virus. The National Association of City and County Health Officials recognized the county Health Department as a “Promising Practice” of 2020. Donuts Delite put Mendoza’s face on a doughnut and couldn’t keep up with demand.

When Mendoza sat down in that conference room, the region had the dubious distinction of having the highest positivity rate in the state. A few days later, the county would hit a new record high of daily cases, followed by another record the next day.

Asked whether he was living a dream or a nightmare, Mendoza replied, “Neither. It’s my job.”

That job has morphed into something distinct from anything anyone in his position experienced before.

His office, for instance, has become a makeshift television studio, equipped with LED lighting to enhance the video news briefings he conducts almost daily.

Behind the door, a giant white board on the wall is a Cartesian coordinate graph that Mendoza drew early in the pandemic to map the spread of the virus. With “Contact Intensity = Distance x Duration” on the X axis and “Risk = Number x Demographic” on the Y, car washes pose the lowest risk of contraction.

A Dr. Anthony Fauci bobble-head doll stands sentry on his desk. “There’s a Michael Mendoza bobble-head doll on the way,” he said in all seriousness. What other Monroe County health commissioner has been a bobble-head?

To some extent, every local health commissioner in the country fell into their newfound role of pandemic posterchild. Few have experience with pandemics.

More so than most, though, Mendoza fell into his.

He had half-heartedly applied for the position when he was appointed by County Executive Cheryl Dinolfo on an interim basis in 2016. As he recalled, he wrote two words in the section of the online application reserved for a cover letter: “Call me.”

“I was very neutral about the job,” Mendoza said. “I wasn’t looking for a job. I wasn’t unhappy with my job.”

At the time, Mendoza was the medical director of Highland Family Medicine, one of the largest family medicine practices in the country, and the commissioner position had become something of a revolving door.

Mendoza became the second interim commissioner in as many years. The previous permanent commissioner, a posting that is to be a six-year term, lasted two years before taking a similar job out of town. The situation got to the point that the state chastised the county for being unable to hold on to a full-time commissioner. County officials claimed no one wanted the job.

He was encouraged to apply by Dr. Jeremy Cushman, who preceded Mendoza as interim commissioner. As Cushman saw it, Mendoza had the pedigree — he holds master’s degrees in public health and business administration — and the temperament.

Mendoza agreed to a full-term appointment in 2017 on the condition that he could continue seeing patients, which he does two days a week. His term expires in early 2023 and he said he intends to serve it out and get re-appointed.

“Let’s face it, Dr. Mendoza is a very effective communicator,” Cushman said. “And yes, he’s a great physician and a great leader of that department. But he is an extremely effective communicator and that’s what we need right now.”

Two days after we talked, Mendoza tweeted a photo of himself being administered the vaccine at Highland Hospital. Then he took the time to answer replies from followers, including a vaccine skeptic.

One regret Mendoza has about his handling of the pandemic is being slow to promote the widespread use of masks. Recall that early in the pandemic the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sent the mixed message that masks do not slow the spread of the virus but should be conserved for healthcare workers.

“I think I had the same feeling that most people had, which was, ‘Shouldn’t any mask be better than no mask?’” Mendoza said. “I wish I had had the confidence in my role to go against the CDC. That’s what it would’ve been at that time. And certainly I would have caught heat for that.”

Mendoza grew up one of two children in the Chicago suburb of Downers Grove. His parents, Filipino immigrants, divorced as he was finishing the third grade and he and his sister were raised by their mother.

She worked at Argonne National Laboratory operated by the University of Chicago, which made Mendoza eligible for a scholarship to the school. He studied environmental science as an undergraduate and attended medical school there.

He completed his residency at the University of California–San Francisco and spent four years practicing family medicine in Chicago before moving to Rochester in 2009. He and his wife, Dr. Lisa Vargish, and their two children, ages 15 and 12, live in Brighton.

There are many casualties of the pandemic, but one of them for Mendoza is the time he has lost with his children.

“I’ve always said, ‘I wanted to be the father I never had,’” Mendoza said. “The casualty of this job for me is that I will probably have missed a good year of time with my kids. I’ve got 12-to-14-hour days every day, I mean, I’m barely there.

“That’s time you never get back,” he added. “That’s the hardest part.”

Back in his office, as I scoured the citations on his wall, he pointed to the one he said was most important to him. “Did you see my ‘M.D.’?” he asked.

It was a framed poem from his children titled, “My Daddy, MD.”

CORRECTION 1.4.21: This article has been updated from its original version to correct a misspelling of the name of Dr. Michael Mendoza's wife. She is Dr. Lisa Vargish.

David Andreatta is CITY's editor. He can be reached at [email protected].