[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Controversies like the death of Philando Castile in St. Paul, Minnesota, keep thrusting actions by police officers into the news, nationally and locally. But conflict between police officers and parts of the community they serve has a long, troubled history, in Rochester as elsewhere.

Some of the conflict stems from the actions of individual officers, some from the actions of people in the community, some from deeply rooted prejudice and suspicion – on both sides.

In St. Paul, the source of the latest conflict was the not-guilty verdict for the officer who shot Philando Castile during a traffic stop. In Rochester, protests erupted after the deaths of Denise Hawkins, Alecia McCuller, Hayden Blackman, and others, shot by on-duty Rochester police officers. Protests have also followed non-fatal injuries of citizens.

Police officers are often called on to react quickly in tense situations, relying on their training, their judgment, and their instincts. But while they may act within defined police procedure, when their judgment is incorrect – when the civilians are unarmed, when they're victims of mistaken identity – the civilians may pay the price with injury or loss of their life.

And the conflict between the police and the community ramps up.

Worsening that conflict, and standing in the way of easing it, is how complaints about police officers' actions are investigated and judged. In Rochester, successive mayors, City Councils, and activists have tried to improve both the system of police oversight and police-community relations in general. City officials have made some changes in both areas, but not major ones. None have done much to lower the tension.

And many people – particularly in the city's poorest, mostly African-American and Hispanic, neighborhoods – not only don't trust the way the city handles complaints about police, they don't trust the police.

Feeding the distrust: Except when criminal charges are filed against an officer, police "police" one another. When civilians file complaints about officers' actions – whether it's about the use of force, courtesy, or police procedure – their complaint is seldom upheld. And the public learns little, if anything, about the outcome of investigations into their actions.

Meantime, bystanders' cellphone videos of the incident have been viewed online for months. Those videos are powerful, and they're accessible to anyone who wants to see them.

Also heightening the distrust: concern that the behavior of Rochester police officers, most of whom are white, is influenced by racial bias.

While charges about police use of force often originate in Rochester's non-white neighborhoods, critics also point to incidents such as a Black Lives Matter protest in downtown Rochester last summer. During that event, police handcuffed and detained 70 protesters – including two African American television reporters who were covering the protest.

Local civil rights leaders have been pushing for change – in police practices and in police oversight – literally for decades.

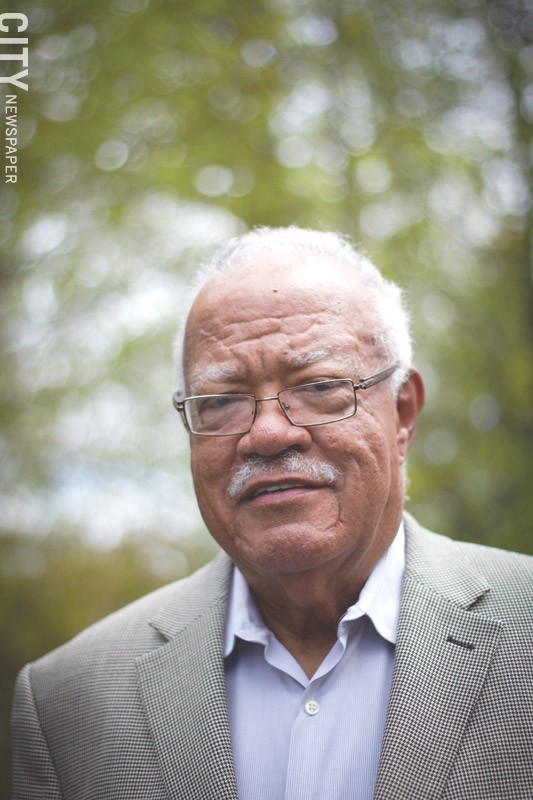

"This is not a new problem," said the Rev. Lewis Stewart, president of the United Christian Ministry of Western New York and leader of the Coalition for Police Reform. "It's an age-old problem."

Stewart and other black leaders were "fighting for the same thing," he recalls, "40 and 50 years ago."

"What is needed," Stewart said, "is a transformation in the way policing is done in this city." And, he said, "The need for change is vital and imperative."

City Council is once again reviewing the way the city handles complaints against police officers. Spurring the action was the case of Rochester teenager Rickey Bryant, who says that last summer, officers responding to reports of a crime knocked him from his bike and beat him, seriously injuring him. Bryant wasn't subsequently charged.

Council members also cite a February report sharply criticizing the oversight process, prepared the citizens groups Enough Is Enough and the Coalition for Police Reform. That report, written by civil-rights activists Barbara Lacker-Ware and Theodore Forsyth, charges that the current police review system fails to hold police accountable for misconduct.

The report calls for scrapping the current system and creating a Police Accountability Board, independent of the police department. The board would have the power to review police policies and procedures, investigate complaints, and recommend disciplinary action, training, and dismissal. And if the police chief did not agree on the discipline, the Accountability Board would determine the discipline.

While it's unlikely that City Council would adopt the report's recommendations wholesale, some public officials, as well as some involved in the current civilian-review system, agree that police oversight needs to be improved. The public, they say, needs to believe that police will protect them, not harm them, and that government will hold officers accountable for misconduct. Lack of trust, they say, makes it harder for police to do their job. And it puts police at risk.

"We've got to understand," former Rochester Mayor Bill Johnson said in an interview earlier this spring, "that erosion of respect for police is as great a threat to public safety as violence."

Currently, if civilians object to treatment by a Rochester police officer – that the officer used excessive force, didn't follow proper procedure, wasn't courteous – they can file a complaint. The investigation into that complaint is done by a section of the Rochester Police Department called the Professional Standards Section.

Police officers in the PSS have been trained not only in police policy and procedure but also in how to conduct investigations. And they attend in-service training during the year at national and regional events.

The PSS interviews the person who filed the complaint, the officers involved in the complaint, and witnesses, if there are any. The interviews are usually done at the PSS offices.

The police chief then reviews the PSS investigation and its findings: whether the complaint is justified or not, or there isn't enough evidence to decide either way. The chief makes a final decision about whether to uphold the complaint, and the chief determines what discipline to impose, if any.

After the police have completed their work, there is a review by a group of civilians: the Civilian Review Board. Operated by the Center for Dispute Settlement, an independent non-profit organization founded in 1973, the Review Board consists of Rochester residents who are assigned to three-person panels to review the investigation by the PSS. They then reach their own decision about whether the complaint was warranted.

Members of the board receive 30 hours of training in mediation and another 40 hours' training on citizens' rights, police policies and procedures, and other topics. During their time on the Review Board, they receive additional in-service training on such things as changes in police policies and court decisions that affect those policies. They're also required to accompany an officer on an eight-hour shift once a year.

If the Review Board panel wants to, it can ask to interview everyone involved in the complaint. But it can't compel them to be interviewed if they don't wish to be.

The Review Board has the right to reach a different conclusion than the PSS and the chief did, and sometimes it does. In 2014, for instance, 58 civilian complaints about the use of force were reviewed. The Civilian Review Board sustained seven of them; the PSS and the chief each sustained three. But with the vast majority of complaints, the Civilian Review Board, the PSS, and the chief all find that there isn't enough evidence to sustain the complaint.

In all cases, the chief's decision is the official finding. And other than the differences in findings being noted in quarterly and annual reports given to City Council, little may come of the Civilian Review Board's involvement.

Complainants are told how the chief ruled, but not how the Civilian Review Board ruled. And no one outside of the RPD and the Review Board knows anything about the investigation other than what the chief decided.

There is one exception to that tightness: City Council itself can ask to review the investigation, and it can subpoena the records. Council has never done that – until now. Earlier this spring, Council asked for records of the investigation into the Rickey Bryant case. But it can't overrule the police chief. And it probably won't be able to say much about what it found in the investigation.

City Council members are currently working their way through the records of Rickey Bryant's case. And they're beginning a review of the oversight process itself. At their June 20 meeting, they approved contracting with the Center for Governmental Research to review the current police oversight system. CGR is also asked to "factor in best practices derived from other cities."

CGR is supposed to complete its work within 60 days. After that, says City Council President Loretta Scott, Council will start assessing the review process. Its work will include looking at the results of CGR's study as well as the Lacker-Ware-Forsyth report.

Council will also be reviewing a list of recommendations for improving the oversight process, which the Center for Dispute Settlement sent it in October. After that, Council will decide what to do.

"It is time for this exhaustive research," Scott said.

Mayor Lovely Warren agrees. "I think that with the things that are happening nationally, it's time to relook at the process," she said in a recent interview.

Warren said she isn't sure the recommendations in the report by Lacker-Ware and Forsyth are "100 percent the way that we should go." But, she said, "I think there is some middle ground. And we're of course ready to explore that."

Nobody argues that the present system is perfect. A common complaint: the lack of transparency about the process and the results of investigations.

Another complaint: that the review process drags on and on. The reasons, police and CDS leaders say, are often related to people's availability: the complainant, witnesses, and the officer involved in the case may not be available when members of the PSS are. A stenographer may not be available when the complainant is.

But things have improved, says Liberti. "There was a time when it would take over 300 business days," he said. Now, he said, the average is about 100 days, "and that's a pretty good turnaround."

Still, the delays are undermining trust and breeding suspicion, especially when cellphone videos and social media have spread the word about an incident.

Another concern: The legislation creating the Civilian Review Board states that there will be 35 panelists, that they'll be volunteers, and that they'll reflect the demographics of city residents. According to the CDS report for the first half of 2016, there were only nine panelists. Only three of them were black, and none were Hispanic. And several were CDS officials or staff members.

Given the extensive time required for training, it isn't easy to find panelists. But Liberti argues that for the Review Board's work to be credible, the training – including training in maintaining neutrality – is essential.

"The training is arduous," he said, "but it brings that level of integrity. They don't bring their biases."

In addition, the Review Board's work often takes place during the day, ruling out many volunteers. And the city's legislation was changed several years ago to require that all Review Board members be city residents, further limiting the pool.

Few members of the public fully understand police procedures, the rights police have, and the limits of the public's rights when interacting with police. If a suspect resists arrest and seems about to attack an officer, police procedure permits the officer to push the suspect to the ground, kneel beside him, and put one knee on top of him.

If police tell a suspect to hold his hands up, so that they're sure he doesn't have a weapon, and instead he reaches toward his pocket or inside a jacket, investigators reviewing the case may decide that the officer was justified in using force – even shooting the suspect.

And yet the public is also aware of cases in which police officers shot an innocent, unarmed civilian because they misjudged his intent when he reached for his driver's license.

Critics of the police "look at it like this individual is completely innocent," said Locust Club president Mike Mazzeo. "What would happen if this individual did have a gun and pulled it out on an officer? We've lived through that."

"There's not going to be a video when a cop puts their hands on an individual and it looks good," said Warren. "Automatically when I have put my hands on you – and that's not just when cops are involved; even when there are two people and a fight ensues – it never looks good."

But the question, Warren said, is whether the police officer acted within proper police procedure: "Did they follow their training? Did they do what they are supposed to do? And if they did, then we have to support them."

"If they didn't," said Warren, "then we have to hold them accountable. And that is a delicate balance. There will never be a time when I have to put my hands on you and you think that it's a good thing. Nobody is going to think that is a good thing."

But, Warren added: "Let me tell you something that we all need to understand. Our police officers have a difficult job, a really difficult job. I've gone out there on the ride-alongs, and the things that they have to see and face and endure day in and day out – it is challenging.

"And you're asking people to be perfect: 'When you go out there, I want everything you say and everything you do to be perfect.' That's our expectation of them. And I can tell you, that is unrealistic, because the situations that they are going into are imperfect.

"You don't know what you're going to find walking into this house. You don't know if this person has a knife. You don't know if this wife or husband has been beaten up or if this child has been abused.

"This is why I say, when I go to these classes and I talk to them, I tell them: 'Follow your training. If you follow your training, then I will go to hell and back with you. If you don't, then we have to hold you accountable."

Holding officers accountable is important both for the public – "so you can build trust in the community" – and for police officers, Warren said.

If new officers joining the RPD find that people aren't held accountable when they do the wrong thing and praised when they do the right thing, Warren said, "you lose them to the negativity."

"You want them to stay encouraged," Warren said, "to believe in justice, to know that Lady Justice is blind, and to be able to apply the law and do the right thing at all times. And you want them to know that when they do that they're going to be supported."

"But if I come out here and I'm with a cop that goes out and busts somebody upside the head and doesn't treat the average citizen with respect," Warren said, "what does that do to me? What does that say about me, seeing that and watching that and knowing that this person is your superior and is not following the law, not following their training, but nothing is happening to them?"

"It goes to that whole movie 'Training Day,'" Warren said. "You lose good people in the process. You lose good cops."

It seems likely that City Council will seek at least some changes to the current process. A big question for Council will be how much change is enough.

City Council president Loretta Scott says she thinks some aspects of the current system are working. But, she added, it's a concern that "the community that is most affected doesn't trust the process, and they don't think it's transparent."

City Councilmember Molly Clifford, who represents Rochester's northwest neighborhoods, agrees. "To the degree that people don't have confidence, we do have to do something," she said. But, she added: "For me, it may be more about transparency and communication and the speed with which the process takes place."

"I think that in the end people want to know the outcome," Mayor Lovely Warren said. "And even though there is a report given, it takes so much time to get that information out there. And especially with cellphone cameras and body cameras and all this different video that circulates out there and is available, I think we definitely need to move the process along faster."

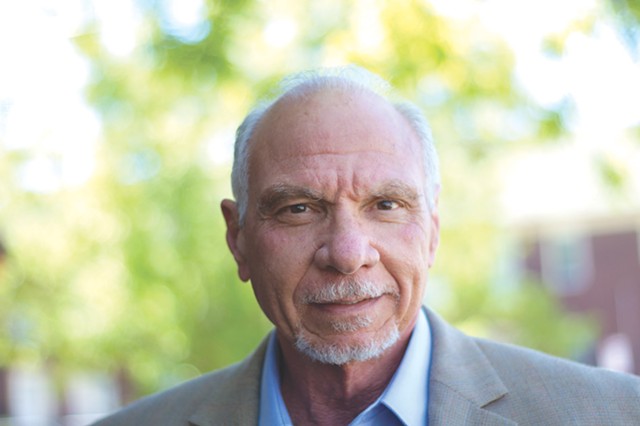

In an interview last week, former Police Chief Jim Sheppard, who is challenging Warren in the September 12 mayoral primary, repeatedly cited four criteria he thinks a police review process must have: It must be complete, thorough, fair, and impartial.

"I believed as chief that we were fair, impartial, complete, and thorough," he said, "but when you step outside" the system, you may see it differently.

"Obviously," Sheppard said, "where we are today, the big issue is trust. No matter how much faith I may have had in the current system, the fact that the community doesn't have that trust – we have to address that issue."

Critics of the current review system may not be satisfied with simply improving the transparency of the process and the speed of investigations, though.

The subject of police oversight has become so "hot," said CDS's Frank Liberti, with high-profile national cases of civilian deaths appearing repeatedly in the news, that "what the public expects in oversight has changed."

The extensive reforms called for in the report by Barbara Lacker-Ware and Theodore Forsyth have gotten wide attention and a good bit of support. The very name of the group they recommend points to dramatic change: it would be an Accountability Board, not a Review Board.

But enacting major reform will be hard, and controversial. And some of the report's recommendations are problematic. For instance, the report calls for an 11-member Police Accountability Board, with some members appointed by City Council and the mayor, and some elected by city voters. Strongly anti-police or pro-police officials could appoint Accountability Board members who share their bias. Elected officials' appointments could be influenced by the political muscle of the police union or citizens groups' protests. Candidates in an election could be heavily funded by, and the results swayed by, the police union or a strongly anti-police citizens group.

If a review board is deliberating complaints about a police officer's actions, said Jim Sheppard, "I don't want you to say I'm guilty because there's a huge public outcry. I want you to say I'm guilty because I've done something wrong."

Neutrality, the Center for Dispute Settlement's Frank Liberti emphasizes, is essential if the public and the police are to trust investigations into police actions.

Former television reporter Rachel Barnhart, who is running for mayor against Sheppard and Warren in September's Democratic primary, is more critical of the current system.

"It's obvious" that it isn't working, she said, because of the few times the Civilian Review Board sustains a complaint – and because City Council hasn't intervened until this year.

"So many times there've been issues that should have raised concerns," she said.

"The current system relies far too heavily on the Professional Standards System," Barnhart said. "There is not enough independent input."

The system "has to have an independent investigator" she said, and she cited the case of Benny Warr, who has charged that police pulled him from his motorized wheelchair and assaulted him as he waited for a bus. "It was a perfect case where de-escalation should have been used" instead of force, Barnhart said.

"I do support police officers, many of whom are my friends," she said. "But I also support accountability."

In their letter to City Council in October, leaders of the Center for Dispute Settlement recommended eight changes. Among them: that the findings of the Civilian Review Board be considered the official findings about complaints, not those of the chief; that "to the extent allowable" by law, the RPD make public "the results of complaint investigations and administrative actions"; and that officers receive a minimum of eight hours of "cultural humility and implicit bias training."

In that letter, the Center did not recommend that investigations be conducted by an independent organization in addition to the RPD's Police Standards Section. But Liberti says CDS has recommended that in the past. And in a recent interview, he and Cheryl Hayward, CDS's director of police and community relations, said they would support that change as long as the investigators were thoroughly trained, including in police policies and procedure.

Long-time civil rights activist Lewis Stewart says he recognizes that Council might not adopt everything the report by Lacker-Ware and Forsyth recommends. But, he said in an interview, some specific changes are essential.

Number 1, he said, is that the new oversight agency has to have subpoena power. "They have to be able to call witnesses to testify," he said. And second: "we need independent investigators."

The Professional Standards Section would conduct its own investigation, he said. "That's their right to do so, but we need an independent body, separate from the Rochester Police Department."

Third, Stewart said, "is that we must find a way of attracting more involvement from community residents" to serve on the review board.

And fourth: "In order for any independent agency to carry out its mandate, it has to be funded. It's got to be funded as an agency under the auspices of City Council. If it's going to carry on this task, it must have a budget of at least $500,000 for the first year. It must be able to hire a director, staff, researcher, and investigators."

"Those are the bare bones," Stewart said. And, he said, the results and the findings of investigations must be publicized.

In addition, Stewart said: "The community also needs to know who is on this agency. Who are the members of the board? There's got to be transparency, not only with the police department but with this whole new civilian review process."

Any proposed changes to the current police oversight process will have to be approved by City Council – and by police officers, since performance reviews and disciplinary measures are covered by collective bargaining.

Buy-in from both Council and police may be a hard sell. For decades, activists have pushed for a more independent, transparent review of police actions, and the current process is the best they've been able to get.

No one, officers say, knows police procedures, and the risks officers face, the way the officers themselves do.

Mike Mazzeo, president of the Locust Club, the police officers' union, says he agrees that the current review system needs to be reformed. But he points to different concerns. The first step, he said, needs to be updating the way investigators are trained to investigate cases involving the use of force.

"You know, science has changed," Mazzeo said. And yet the training about investigations into the use of force is the same as it was 30 or 40 years ago.

This fall, the union is bringing in experts on force, at the union's expense. "That's needed especially in light of body cameras, cellphone cameras, pole cameras, and all this other technology," Mazzeo said. "You know, you don't simply look at a video and determine that they did this or they did that."

"Our officers are reviewed under a process that is not current," Mazzeo said, "nor has it been updated in any way, shape, or form."

"We want that kind of reform," he said.

And, he said, the current system of deciding whether and how an officer will be disciplined should be changed, perhaps having a neutral hearing officer make the final decision, rather than the police chief.

Police departments often object to having anyone other than police officers investigate their actions. Mark Simmons, deputy chief of the Rochester Police Department, is not quite as resistant. Asked whether he thought police would agree to let an independent agency conduct investigations if the investigators were thoroughly trained in police policy and procedure, he said this: "I think the answer lies in that big word 'if.'

"Under perfect conditions, I think it would be acceptable," he said. "I wouldn't go so far as saying it would be ideal."

The officers assigned to the Police Standards Section are carefully trained, he said. They understand police policy, and they understand police procedure.

"It's not just training, taking a 6-hour or a 40-hour course," Simmons said. "Nothing beats experiential knowledge."

"If you're going to have investigative powers," said Mayor Lovely Warren, "who is going to be doing that investigating? Are you going to hire retired police officers? Retired investigators?"

"You can't just have anybody investigating," said Warren, "so I really think that is one of the big questions out there that needs to be answered. What do you really truly consider independent?"

The current system of handling citizen complaints isn't the only issue at the heart of strained police-community relations. Another is police training. And police staffing.

"Officers have a lot of discretion," says the CDS's Frank Liberti. What police procedure permits officers to do isn't necessarily what's best. "We need to get officers to 'Should I do this" from 'Can I do this,'" says Liberti.

Officers also need extensive training in racism and cultural bias, to help overcome deep-seated racism and innate biases of all kinds, something that's particularly important when people of different races and ethnic backgrounds interact in volatile situations.

And CDS's Cheryl Hayward emphasizes the need for police to build relationships in the community. Officers who know the young people on their beat, who know the adults on their beat, know the families on their beat, may respond differently in volatile situations. They may know, for instance, that a teenager who is acting out is usually well behaved, and they may figure he simply has had a rough day.

That assumes that officers have not only received adequate training – including in bias – but also that police staffing patterns give officers time to get to know the people in the community, to walk the streets, attend community functions, hang out at corner stores, set up police-neighborhood sports competitions.

And that would require hiring more police officers, and having them assigned to small enough areas of the community that they could get to know residents and participate in community life.

Since then, however, city officials have taken steps that may have made that harder. At one time, police officers served in one of seven sections of the city, working out of an office in that section. In 2004, in an effort to save money, the city reduced the number of sections to two, assigning more officers to the section with the highest police service needs.

In 2014, the Warren administration took the number of patrols back to five, but there still aren't section offices in all of those patrol areas. The police union has argued that those physical structures help the officers in those sections interact with the community and be a part of the community's infrastructure.

And RIT's John Klofas says that the city needs to commit to real community policing.

"The RPD, he said, "tends to be really driven by 911 calls. The police who are on duty anytime are really running from one 911 call to another 911 call."

Police aren't able to spend much time walking around, Klofas said. They don't have time to get to know people.

True community policing also takes training, he said, and while there are federal resources that provide the training, at no charge, the city hasn't taken advantage of them, he said.

If Rochester changes the way it handles civilian complaints about police officers, whatever form that takes will have to create a higher level of trust if it is to be effective. City residents will have to trust the system and the police. And police officers will have to believe the system will protect not only their rights but also their safety.

But a huge obstacle is the state's civil service law, which protects the confidentiality of police personnel records. Unless police action results in criminal charges, the public usually doesn't learn the names of officers involved in complaints. And even if the police chief sustains a complaint and disciplines an officer, the person filing the complaint doesn't learn what that discipline is.

Changing that would require changing state law – a major challenge, given the strength of police unions statewide. But former Mayor Bill Johnson says that despite the challenge, the public should push for change. With citizens able to capture police actions on cellphones and share them on social media, greater transparency is in the interests of police as well as the general public.

And Johnson says attitudes need to change on both sides of the police-review issue. Police need to understand that it's in their interest for all parts of the community to trust them. And, he says, critics of the current system need to understand that a very small fraction of police actions involve misconduct.

"We get over 400,000 calls a year," said Locust Club president Mike Mazzeo. But the media and critics of the police, he said, tend to focus on a handful of incidents involving the use of force.

Despite the difficulties involved, some other cities have found ways to investigate police conduct with greater civilian involvement. Rochester, however, "is on the low end of the scale," said RIT's John Klofas.

Former Mayor Johnson argues that a better system is both achievable and crucial. "The infrastructure, human and structural, for making these reforms in Rochester exists," he said in an e-mail. "In fact, citizens are more engaged than 20 years ago. We just need to restore the trust between the parties. And to change current state law to facilitate the changes."

A recent report on police oversight is sharply critical of the way the city currently handles civilian complaints into alleged police misconduct, and it calls for major reforms.

Prepared by activists Barbara Lacker-Ware and Theodore Forsyth for the citizens’ groups Enough Is Enough and the Coalition for Police Reform, recommends scrapping the current process entirely and replacing it with an autonomous Police Accountability Board.

Some of the report’s recommendations aren’t feasible; state law, for instance, prohibits sharing information about the discipline of a police officer. And even some activists agree that it’s unlikely that all of the report’s recommendations would be adopted. But the report has helped focus attention on the issue – including at City Hall.

Among the report’s recommendations:

• The Police Accountability Board would have 11 members, all city residents. The report originally recommended that six members be elected by voters, four appointed by City Council, and one appointed by the mayor. The report's authors say they have since rejected that idea and are "fleshing out a community appointment process."

• Board members would be trained not only in police policies and procedures but also in such areas as civil and human-rights laws, racism, gender and sexual-orientation issues, and disability rights.

• The Board would have an administrator, a staff, and an independent investigator or investigators.

• It would evaluate police “policies, procedures, and practices” and recommend changes if it had them. It would conduct investigations into allegations of police misconduct. And it would have subpoena power.

• The police department’s Professional Standards Section, which currently conducts reviews of complaints against police, would give the Police Advisory Board its reports and its files of the investigations into complaints.

• If the Accountability Board found that there was misconduct, it could recommend discipline, training, or dismissal.

• The police chief would share findings and disciplinary recommendations with the Accountability Board. And if the Accountability Board and the police chief weren’t able to agree on the discipline, the board would have the final say.

The full report is available here: http://enoughisenough.rocus.org/police-accountability-board.com

Investigations into civilian complaints about Rochester Police officers are done by the Police Standards Section of the police department and are then reviewed by both the police chief and the Civilian Review Board. All three reach one of four “findings” about the complaint:

• Sustained – The act did happen, and the officer acted improperly.

• Unprovable – There wasn’t enough

evidence to prove whether the complaint is true or false.• Unfounded – the investigation didn’t find evidence that the act took place.

• Exonerated – the officer’s action was appropriate and justified.

Speaking of...

Latest in News

More by Tim Louis Macaluso

-

RCSD financial crisis builds

Sep 23, 2019 -

RCSD facing spending concerns

Sep 20, 2019 -

Education forum tomorrow night for downtown residents

Sep 17, 2019 - More »

More by Mary Anna Towler

-

Police reform: advocates on what should come next

Oct 22, 2019 -

Court clears the way for Police Accountability referendum

Oct 17, 2019 -

Dade outlines initial actions on district deficit

Oct 9, 2019 - More »