[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Vivian Dooher was 4 months old when her pediatrician noticed she had low muscle tone and wasn't making eye contact.

The doctor made those observations during a routine wellness visit, and the baby's parents, Kim and James Dooher, immediately sought Early Intervention services for her. The county-administered program connects families of children with confirmed developmental delays and disabilities to an array of therapists, educators, and social workers, who provide services at no cost to the families.

By the time Vivian was 5 months old, she had gone through the intake and evaluation process and had begun receiving services. She was ultimately found to have a significant developmental delay, says Kim Dooher.

"I remember the day of the evaluation, and I remember the shock," Kim Dooher says. "I remember just being completely dumbfounded with how many needs she had and how many services she was going to need. It was just shocking. It was devastating."

Vivian is now 2½ years old, and she's received services including physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, and a specialized teacher of the visually impaired. At one point, Vivian was having trouble eating and swallowing, but a nutritionist and speech therapist worked with the girl and her family to address that issue.

Kim Dooher says the services and her daughter's early access to them are "the reason why she's able to eat food and run and read books with me and all those wonderful things that kids are supposed to be doing."

But Monroe County's Early Intervention services are in crisis, just as they are in counties across the state. The county is responsible for operating the program, but it doesn't set reimbursement rates for providers; the state does. And New York officials haven't raised the reimbursement rates for providers in nearly 20 years, leading crucial therapists, specialized teachers, and other professionals to take better-paying jobs at institutions and agencies.

As a result of a growing provider shortage, an increasing number of families – as many as 195 by one recent account – are currently waiting for services. Children with complex needs and their families "have sometimes waited for weeks, months, upwards of even a year to gain access to the very services they need," says Monroe County spokesperson Jesse Sleezer.

An April 2018 report by The Children's Agenda laid out what's been happening with the Early Intervention system in Monroe County and statewide. It shows a program that's overburdened and underfunded, and promotes the consensus that the state needs to fix the problem it has caused.

Early Intervention's troubles are evident at the point where children first enter the program. Families may be referred to the program by someone like a physician or day care staff member who sees warning signs, or they can act on their own if they suspect a developmental delay or disability.

From the start, families work with a service coordinator who guides them through intake, screening, and developing a services plan for their children. Later, a service coordinator helps track the child's progress and determine whether services need to be changed or expanded.

And Monroe County faced an urgent problem with service coordination at the end of 2018.

Over the past few years, several agencies stopped providing service coordination for the county, largely because the state reimbursement rates weren't enough to cover their costs. Catholic Family Center stuck it out but in December finally pulled out of the program (though it still does some service coordination for its Medicaid Health Homes clients).

Since the county is legally required to provide for service coordination, it had to absorb Catholic Family Center's clients, which it wasn't staffed for. Children who were referred to the program had to wait for evaluations and service plans, though the county officials quickly scrapped a formal waitlist proposal they floated.

This year, the county has added three service coordinators, bringing its total up to 15. That's a shadow of the approximately 40 privately employed service coordinators that have left the program over the past five years.

The county also shifted some support staff to assist the coordinators, so they can spend more time working with clients and less on tasks such as paperwork. Democratic county legislators, as well as some advocates and parents, pushed for the county to add an additional six service coordinators. A budget amendment introduced by the Democrats was rejected by the legislature's Republican majority.

Even though the county added service coordination staff, some families still have to wait longer than they should, advocates say. The county has 45 days after a child is referred to the program to conduct an evaluation and put together a services plan.

"What we've been saying is that in that case, most parents will find that the process has worked as it typically has with the county," says Monroe County spokesperson Jesse Sleezer.

The county and children's advocates readily acknowledge that Catholic Family Center officials simply did what they had to, and that they aren't acting unreasonably. Center officials say they could no longer afford to run a program staffed by qualified, knowledgeable people because the organization wasn't getting paid enough by the state.

"It broke our hearts to actually have to stop doing the ongoing service coordination, because we've actually been providing that service since 1998," says Jennifer Berenson, Catholic Family Center's director of children, youth, and family services.

And while reimbursement rates stagnated, the organization's caseloads saw a dramatic increase. It served around 350 to 360 children a year in the early 2000's, but that number rose by about 600 children a year for each of the past few years.

Catholic Family Center, like all Early Intervention service providers, wasn't reimbursed by the state for time its staff spent traveling to see clients at their homes, doctors offices, or businesses; filling out or filing paperwork; or filing insurance claims – a step the state requires before it makes payment. (Advocates, county officials, and state lawmakers say insurance companies deny most Early Intervention claims.)

"The cost of doing business was really – it just wasn't there," Berenson says.

But even if the service coordination side of Early Intervention were more robust, there's another problem, one that's potentially more serious.

"We just simply don't have enough Early Intervention providers in the community here," says Pete Nabozny, director of policy for The Children's Agenda and the author of the organization's report on Early Intervention problems in Monroe County.

Again, money is a driving issue. Individual professionals – therapists and teachers, for example – enter the field because they want to help children. But often, the low pay catches up with them, and the jobs are in high demand in other fields. Speech therapists are also in demand at schools and in hospital stroke care units. Physical therapists might make $20,000 a year more working for a health care provider than they would through Early Intervention programs, Nabozny says.

The agencies that provide Early Intervention service "have unfilled positions all the time and they can't afford to pay more, because they'll go broke that way," Nabozny says.

Vanessa Stewart has experienced Monroe County's provider shortage firsthand.

She and her husband have a 3-year-old daughter who has severe hearing loss and needs a teacher of the deaf, a special education teacher with a background in hearing loss. The teacher would help her daughter with learning and communication strategies, as well as helping her learn to use her hearing aids and assistive devices such as a digital media system for communication.

A teacher of the deaf would also work with the 3-year-old's parents and teachers, learning and communication strategies for her. (Stewart requested that CITY withhold her daughter's name.)

Stewart says her daughter began receiving Early Intervention services shortly after an audiologist confirmed her hearing loss in December 2016. She worked with one teacher of the deaf, who left for a better-paying job at a school district. That teacher was replaced by another teacher of the deaf, who in September 2018 also left for a better-paying job in a school district, Stewart says.

"If districts are hiring, of course you're going to go into the district where you're getting great health insurance, you're doubling your salary," Stewart says. "So of course you're going to make that jump."

There aren't currently any teachers of the deaf in Monroe County who are available during the day, when they'd be able to work with the staff at St. John Fisher College's Early Learning Center, where Stewart's daughter goes for day care. A teacher of the deaf would help staff at the center learn strategies for working with her hard-of-hearing daughter, and would help her daughter interact with others.

Stewart's daughter has aged out of the Early Intervention program and is now in the related Preschool Special Education program. The county also administers Preschool Special Education, although school districts develop education-based service plans – individualized education programs, aka IEP's – for the children.

Unlike Early Intervention, the county sets reimbursement rates for Preschool Special Education services, and recently, County Executive Cheryl Dinolfo introduced legislation that would raise the program's reimbursement rates by 15 percent. If passed, it'll be the first increase in a decade.

Dinolfo, a Republican, is seeking reelection and her opponent, Democratic County Clerk Adam Bello, welcomed the increase but criticized the exec for not moving to raise rates sooner.

The Preschool Special Education Program isn't in the dire straits that Early Intervention is, though Nabozny and other children's advocates say there are provider shortages that affect the services children receive, and that could intensify if reimbursement rates aren't brought up further.

The situation that Stewart's daughter is in shows that not all is well. The Pittsford school district has her on a waitlist for a teacher of the deaf services, and for now, it's providing extra speech therapy. But Stewart says her daughter needs the former more than the latter, so she's looking for alternatives.

"It's really a hard, emotionally draining job," Stewart says. "I'll be honest with you."

Stewart is a special education teacher herself, but she doesn't have any background in hearing loss, which she mentions to emphasize the value of teachers of the deaf.

"I'm learning as I go," she says, "and that shouldn't be the case. I should be an advocate for my daughter, and I should be a professional as well, and I don't feel like I am because of this shortage."

Vivian Dooher will soon be shifting into the Preschool Special Education program, and her mother doesn't expect a seamless transition. She hopes her daughter gets into the right setting, but she also realizes that "people have to actually exist for her to get the services." So she's nervous.

"I'm hoping that the evaluators are going to be honest about what she needs and not just say that she needs what they have," Kim Dooher says.

So what can be done to fix Early Intervention and Preschool Special Education programs in Monroe County and across New York?

The general consensus – from parents, from providers, from children's advocates, from county officials, from municipal government associations, from state legislators – is that the state needs to pay providers more.

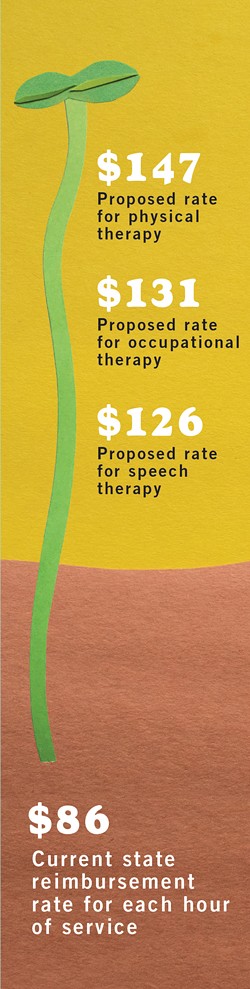

The current reimbursement rates are pretty far out of whack with provider costs, especially staff salaries. In its 2018 report, The Children's Agenda said the state needs to substantially raise rates across the board for Early Intervention services. It calculates how much the state needs to raise rates for three key services in order for the people who do the work to receive regional median wages for their professions, as well as competitive benefits.

The state's Early Intervention reimbursement rate for occupational therapy, physical therapy, and speech therapy is $86 for each hour of service. The Children's Agenda report says the state should raise the occupational therapy rate to $131 an hour, the physical therapy rate to $147 an hour, and speech therapy to $126 an hour.

It also recommends equalizing the rates between Early Intervention and Preschool Special Education. Dinolfo's proposed Preschool Special Education rate increase isn't enough to match the rates proposed by The Children's Agenda.

The Children's Agenda report also suggests that the state consider reorganizing the Early Intervention and Preschool Special Education programs so that they are one consistent, coordinated effort serving children up to age 5. The state should set the rates, the report says, and it should establish a methodology to do it that's grounded in providers' actual costs.

Governor Andrew Cuomo included an Early Intervention rate increase in his 2019-20 executive budget proposal, but it would bump reimbursement rates up by only 5 percent, and the increase would be only for select providers.

Assembly Democrats went further and proposed a 5 percent increase in the rate for all providers, including service coordinators. Their one-house proposal also would have created a new "covered lives assessment" on private health insurance companies, which notoriously reject a very high percentage of Early Intervention service claims; the state ultimately reimburses the providers in those cases.

The tax on insurance companies would have generated a $16 million pool for Early Intervention services and would have served to separate discussions about the program's reimbursement rates from discussions around the budget's general fund.

"If we're able to pull this funding source out and actually move ahead with creating a separate, outside pool, it'll be much easier in a few years to get the funding increase," says Assembly member Jamie Romeo, a Democrat from Irondequoit.

Romeo acknowledges that there is an immediate, statewide crisis and that the covered lives assessment is a longer-term approach. She says it'll be important to come up with short-term plans as well.

But the Assembly proposal didn't survive budget negotiations. The final state budget, passed by the Assembly and Senate on Sunday, keeps the governor's plan to increase reimbursement rates by 5 percent for some – not all — providers.

New York didn't have to get to this point. "The reality is the state could have been taking incremental action over time, made sure these rates stayed in line with providing the service," says Monroe County's Sleezer. "But it didn't."

Now there's a crisis hitting every county in the state. Early Intervention programs are losing providers to better paying jobs, and as a result, families are facing delays when they seek services for a child. In some cases, the services aren't available at all.

When children don't receive the support they need, it can cost school districts down the line as they try to make up for lost time. But the overburdened, underfunded system's true failing is that it's robbing children of a chance to thrive as best they can.

The providers who have worked with Vivian and her family are responsible for so much of her progress and development, Kim Dooher says. She worries about the "moral injury" the state is inflicting on providers, who have to choose between important work they're passionate about and financial realities like student loans, mortgages, and supporting their own families. And she worries about the children and families who are suffering because they can't get the life-altering services that helped her own daughter, she says.

"It's a really scary situation," Dooher says. "It's only going to get worse."