[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

The Rochester school district has been under fire for decades. There've been countless rallies, protests, consultant reports, and blue-ribbon panels. Newspaper editorial writers and other critics have accused the school board and union leaders of being more interested in protecting their own interests than in educating children. And teachers and staff have often expressed frustration, saying they're accused of not caring about their students.

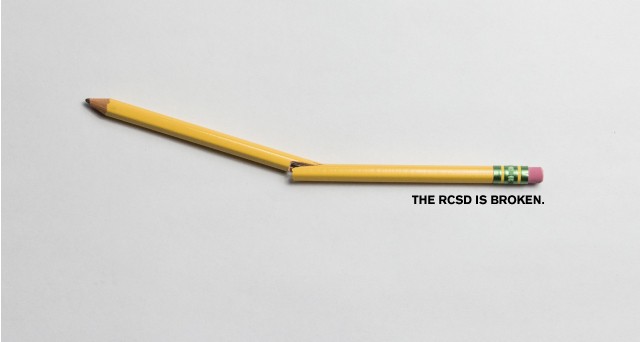

Distinguished Educator Jaime Aquino's highly anticipated assessment of the Rochester school district, released last week, offers both new and previously reported insights. But this isn't just one more report. Comments made by State Education Commissioner MaryEllen Elia and Chancellor Betty Rosa at last week's press conference made it clear: the Rochester school system is broken, and state officials don't intend to let it stay that way.

"Right now, we have a situation I would classify as a crisis," Rosa said. "This is not acceptable."

Calling the report an "indictment," Elia and Rosa gave Rochester school officials an ultimatum: The district has reached the end of the road. Change is coming. Get on board or get out of the way.

The report isn't a thorough analysis of the problems in the district's operations. It couldn't be, given the 45-day deadline Aquino had. Some of Aquino's charges are based on anecdotal information rather than hard data, as board President Van White noted in his response to the report.

And Aquino dismissed or downplayed the importance of some of the challenges facing urban districts like Rochester's. Still, his blunt, hard-hitting 60-page report portrays a district in need of serious reform.

Aquino's report spares virtually no area in the district from criticism, and it's full of references to past reports, underscoring the fact that the district's problems have been well known for years.

Aquino describes a school board that isn't unified, doesn't even agree on what its own role is, doesn't understand the district's finances, and oversteps its boundaries. He describes a district that lacks cohesive, effective management – partly due to too much turnover in top leadership.

Among his conclusions:

On the school board's role

From the report: "Board Commissioners could not clearly define their roles and responsibilities, which interfered with the superintendent's ability to lead effectively.... Commissioners need to be reminded that the Board's main responsibilities include making policy, overseeing the budget, and selecting and evaluating the superintendent."

Aquino's report is extremely critical of the school board. At times, it says, the board has sidelined the superintendent and blurred the line between governance and management. This board and some previous boards, the report notes, haven't seen their role as being limited to the traditional: making policy, approving budgets, and hiring superintendents. Some board members have been too hands-on in the management of the district and too willing to take over some of the superintendent's responsibilities, the report says.

The report calls for a more unified relationship among board members and between board members and the superintendent. Currently, personality clashes spill into public view, it says. And Aquino recommends training for board members on how to be more effective as a unit.

Aquino criticizes the board for not holding superintendents accountable for enforcing board policies and directives. An example: More than a year ago, the board voted to make School 33 a feeder school for East High school. School 33 administrators didn't fully support the idea and resisted implementing it, though, and the board didn't hold the superintendent accountable for carrying out their decision, so the change hasn't been fully implemented.

On leadership instability

From the report: "The district has undergone a significant leadership turnover at the top: five superintendents in the last 10 years."

Board leaders have insisted that changes in superintendents won't affect the district's efforts to improve student achievement, but the report says the negative effects of the district's near constant change in leadership are obvious.

In addition, the report notes that leadership changes haven't been limited to superintendents. Deputy superintendents, school "chiefs" – who are responsible for groups of schools – and school principals change frequently, resulting in new directions and new priorities, and a failure to implement previous district decisions.

For instance, the district's troubled special education program has put the district in legal jeopardy for not complying with laws and regulations. Because the department has had "seven executive directors in the last ten years – five since 2016 – and a current director who has been in the position for less than a year, leadership has been lacking," the report says.

The lack of effective leadership is so widespread that it's not even clear who is ultimately responsible for special education students, the report says.

The report also shines a spotlight on one of the most serious consequences of the frequent leadership changes: the inability to implement even basic elements of school management, such as correctly taking attendance. The latter may have contributed to one of the most tragic incidents in the district's history – the death of a student.

On teaching and learning

From the report: "Curriculum programs vary greatly across content areas and grade levels. As a result, teaching staff lack the necessary guidance about what to teach, when and how to teach it, and the best tools for assessing student learning."

For a variety of reasons, many families in the city move frequently, which makes a common curriculum used across the district extremely important. But the Rochester district doesn't have one. Aquino's report notes that the rate of in-district student mobility in city schools is somewhere around 25 percent. That means students moving from one city school to another may fall behind when they get to their new school if it isn't using the curriculum the student was used to working with.

The report suggests that not having a common curriculum can lead to more students needing intervention services. It can also contribute to over-identifying students as needing special education services, the report says.

On accountability

From the report: "There is no performance management system.... Supervisors, including the superintendent, are often not aware of the work of their direct reports.... An often heard complaint is that no one is held accountable for poor performance. On the contrary, it has been reported that the district rewards poor work by promoting staff that have not been successful, demoralizing those who work diligently."

Aquino's report describes an organization that is extraordinarily complacent about accountability, and that failure has impacted morale. Teachers and community activists complain about ineffective teachers and administrators who get moved to a different school or to central office instead of being fired.

Those complaints are echoed by new school board members Beatriz LeBron and Natalie Sheppard, both of whom in their professional lives have worked with the district. The district has many hard-working and gifted teachers and administrators, the two board members say, but too often, ineffective people keep their jobs when they should be let go.

This has been a common complaint for decades, and critics often accuse the district's unions of protecting ineffective employees. Union leaders insist that they don't condone poor performance but that teachers and administrators have a right to due process.

Has the district failed in this responsibility because evaluating performance, documenting problems, and removing ineffective employees is too time-consuming?

Do superintendents and supervisors feel they don't have the authority to hold others accountable or that their personnel decisions will be challenged and overturned?

Or do administrators fear retaliation and think that writing someone up isn't worth the political upheaval it may cause?

Aquino's report doesn't raise those questions, but the lack of accountability in performance oversight is another example of the district's problems in leadership.

On finances

From the report: "Most stakeholders (Board, administrators, teachers, parents, and community members) lack any real understanding of the serious implications of the district's structural deficit. Some seem to believe that funding will always be available. The chief financial officer has shared with the board that 'If this continues, the District's finances will hit rock bottom within three-to-five years.'"

The district's budget is now just shy of $1 billion. Some community members, including some current and former City Council members, have criticized the district's finances, calling its budget bloated and mismanaged.

Last week, while presenting his report, Aquino didn't make that specific criticism. But he did say that the district is not short of money and that it has enough to do its job.

"Most schools," his report says, "appear to be generously staffed with little thought given to long-term sustainability."

It's unclear whether additional staffing would improve student outcomes, the report says. Aquino also pointed to a wide disparity in the distribution of funding and services among schools.

"The total school funding per pupil ranges from a low of $17,414.20 to a high of $36,103.35," the report says, "with a mean of $21,472.65."

Aquino criticized how the district manages its finances, said the board as a whole doesn't understand the finances, and said the board relies too heavily on a three-person board committee for its financial oversight. As a result, the board sometimes doesn't notice problems when they exist. In some instances, for example, contracts exceeding $35,000 haven't been submitted to the board for prior approval, which is a board policy.

There's a strong possibility that the district will face a financial shortfall in the next several years if the board and the superintendent don't head it off, Aquino said, and yet there is no sense of urgency concerning the district's finances.

Much of the report was highly critical of the district and its leaders, but Aquino did point out some bright spots. The district's Pre-K program is generally recognized as one of the best in the country, his report says. And there's been a concerted effort to improve school climate, provide training in cultural competency, and reform the district's approach to student discipline – which has led to reduction in the suspension rate in some city schools.

After years of complaints from parents, students, and community activists, the district has been provided some training to try to eliminate racism in the district. But "racism has not been fully acknowledged and does not inform school practices," the report says.

Although his report lists numerous problems that an effective district should be able to correct, Aquino seems to downplay or overlook some key challenges facing urban districts.

For instance, Rochester's child poverty rate is one of the highest in the country. More than 80 percent of city students are eligible for free and reduced-price meals. Many school officials report that the meals that some children receive in school are their main source of nutrition.

Hundreds of Rochester school children are homeless at any given time, according to some reports. And many more enter school unprepared and already behind in basic skills, making early childhood development programs a necessity. On the whole, the report hardly mentions parental responsibility.

Rochester is home to many immigrants, and nearly 100 different languages are spoken by children in city schools. That problem intensified last year, when the district took in about 500 students from Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria devastated the island. Many spoke no English.

Aquino makes little reference to factors like these and their impact on city students and their families. And the report dismisses the district's high poverty rate and the real cost of education and providing students with the services that Elia and Rosa said they "need and deserve."

Though the report mentions that the district is trying to address the challenges that stem from childhood trauma and mental health problems, the district has struggled to hire enough social workers within its budget.

And although the district does receive some support from outside agencies in areas like mental health, the need for all types of family support services remains high in Rochester.

As with most reports like this one, Aquino's doesn't cite examples of successful large urban school districts that could serve as models for Rochester: large, high-poverty school districts with graduation rates in the mid-90's and college and career-ready students.

While there are examples of high-performing schools in high-poverty districts, high-performing urban districts are rare.

Aquino's report also gives short shrift to one of the district's recent success stories: the partnership with the University of Rochester at East High School.

Ironically, the report's sole reference to East High was its $36,000 per student costs. The school has shown the most dramatic student achievement increase in the district in the last two years – due in large part to an investment in providing students with emotional support.

Although the report calls for labor agreements that are less generous to the unionized employees, that won't be easy to negotiate

Aquino's report also glosses over the complexities of the relationship between the school board and the superintendent. For instance, the report seems to minimize some of the challenges of an elected school board becoming a unified body. Not all board members run for office to be unifiers. Some campaign instead on being disruptors who will shake up the system. And as Aquino notes, that can leave a superintendent with seven different bosses, each with a different idea of why they're there.

Board members also reflect the public's priorities, which change over time. For example, when former Superintendent Jean-Claude Brizard left, many activists urged the school board to hire someone local to succeed him. His successors, Bolgen Vargas and now Barbara Deane-Williams, are local, but the board ended up dissatisfied with both.

And when a board hires a superintendent and a year later finds that he or she isn't living up to its expectations, it has few options. It can try to get the superintendent to change, but if it's not successful it can buy out the contract, look for a new one, and cope with the resulting instability, or it can try to live with the superintendent's shortcomings.

For all of the report's emphasis on reducing leadership change, the Rochester school district is entering a phase of particularly intense change. Last winter, three new members joined the seven-member school board: Melanie Funchess and Beatriz LeBron were appointed to fill unexpired terms, and Natalie Sheppard joined as a new elected board member. Earlier this month, Funchess lost her seat to Judith Davis, who will join the board in January, shortly before the superintendent leaves.

In the coming months, the board with its three new members will have to agree on an interim superintendent and a permanent superintendent, which may be particularly difficult given the current divisions on the board.

And it will need to work with Aquino, who will stay with the district into next year to help create yet another improvement plan, which has to be submitted to Elia in February. But the hard job is not writing another plan. As the report emphasizes, the hard work is in implementation, sustained leadership, and hiring and training strong management.