[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Scott Hetsko had to nearly die twice before he could really live again.

One of those times — what he calls the lowest point of his whole, nearly 10-year ordeal — his heart was in arrest for over two minutes until medical staff in the cardiac unit at the University of Rochester Medical Center could revive him.

"They were waiting and waiting and CPR-ing and all that, and they woke me up with a 'zap' and I made it back," he says. "For me, it was like going to bed. I woke up and my chest was on fire because they shocked me."

You get the impression from watching Hetsko that this is a man who is all in, that the barely contained energy crammed inside his lean, athletic frame is just waiting for permission to explode. On television —he's a meteorologist for 13WHAM News — Hetsko comes off as affable and wholesome, so when he lets slip the occasional expletive during this interview, it's just a bit jarring.

Most of us move through life vaguely aware of our impermanence, but Hetsko feels every tick off the clock acutely, and he's determined to make the most of whatever time he has left, for himself, for his family, and for Shawn — the man who gave him his heart.

Hetsko, now 46, had cardiac sarcoidosis — a rare autoimmune disease in which the body attacks itself. The cause is unknown. Inflammatory cells invade the heart, destroying the organ's muscle tissue. The fibrous tissue that replaces the muscle tissue doesn't contract very well, and the heart becomes electrically unstable.

The combination puts the sufferer at risk of sudden death. In Hetsko's case, the risk was moderately high, says Dr. Leway Chen, UR Medicine transplant cardiologist.

Hetsko kept his battle to himself for the most part, which is not easy to do when you're a popular public figure and well-meaning people feel entitled to share in even the most intimate details of your life. Publicly, all Hetsko said was that he was dealing with a health problem and had to step away from work for an undetermined amount of time.

What was happening was that he was waiting for a new heart. He spent three months in the hospital waiting — donors and recipients are matched based on a number of criteria — and then five more recovering after the operation. He was lucky: his overall good health, his relative youth, and his favorable blood type helped him get a heart relatively quickly; 22 people die every day in the US waiting for an organ transplant, according to the Finger Lakes Donor Recovery Network.

Hetsko's recovery has been optimal; he's had no reason to go back to the hospital except for routine tests. That's the good news. The not-so-good news is that the clock is ticking. A donor heart lasts, on average, 11 years. The longest anyone's ever lived with one is 33 years.

"Our bodies are pretty smart," Chen says, "and they realize that, 'Hey, this is something that's not me,' and are constantly trying to attack the heart and get rid of it."

The main reason that heart transplant patients don't survive indefinitely is because the medications they take to reduce the risk of rejection have serious side effects and can cause kidney failure and other problems.

Hetsko has absorbed this information, and it's changed the way he lives his life.

"It makes me think differently about everything I do," he says. "I don't think 30 years out anymore. I'm not going to worry about my retirement."

"When I built the kids a nice play set out back, I didn't care about the cost of it, because it's just money. This is happiness now, and this is the time we have now. I don't know if I'm going to live to see my grandkids. But I know I have my family now, so that's what I'm going to live in."

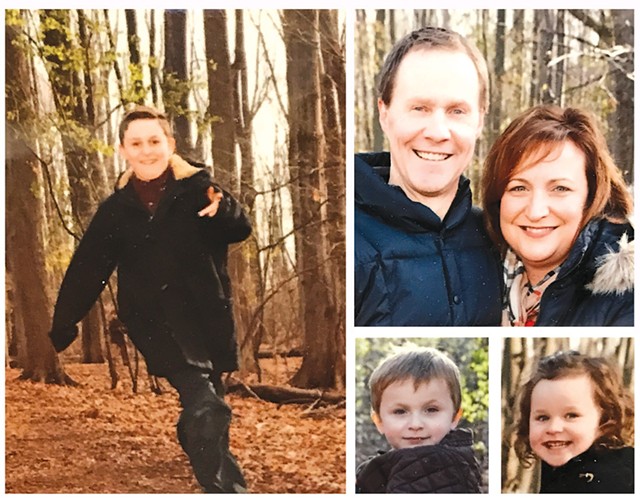

Hetsko is married and has three young children: 11-year-old Logan and 4-year-old twins Julia and Jack.

He talked to CITY recently about his ordeal and how it affects his life. The following is an edited version of that discussion.

CITY: When did things start going wrong with your heart?

Hetsko: It was March 12, 2009. You tend to remember the dates when this stuff happens.

I got really sick in February of that year. Couldn't really do a whole lot: couldn't walk, couldn't move without feeling really tired and short of breath. When your heart enlarges, it can't squeeze and pump. It's like you're in your own human prison.

I had to go to the hospital, and that night I was told I needed a pacemaker. I didn't know what the hell a pacemaker did. So the next morning, I had a pacemaker installed.

The first doctor told me to consider getting my affairs in order, which really scared the hell out of me.

Basically, what I was told was, "We don't know exactly what happened, but we think it's sarcoid, because we saw it in your lungs. And we don't think it's worth it to do a biopsy on your heart at this point. And you're probably going to need a heart transplant someday. And we think it's going to be nine months."

It messes you up in every mental way it can. You learn to live with it. I lived pretty well for about four, five years with the condition. I never felt good a day in my life, but I could go on. Even with the pacemaker, you can't do so much.

The pacemaker did its job, but the heart over time just got sicker and sicker, and you just can't stop that without doing something invasive.

And they basically said, "You're not going to make it through the summer if you don't come in."

Were you confident that you would get a heart?

It's hard to get a heart. Out of the 100 percent of people who need a heart, only about 34 percent get one. So, 66 percent don't make it.

I came in with the information that I was the only guy waiting who was my body type — so I was, like, the top of the list for a guy like me. Because it's a competition. If there's another guy like me who's been there before me, he gets the heart first.

What was your reaction when you found out that a heart was available?

I said, "You're fucking kidding me." That's exactly what I said. And then I cried.

What do you know about your donor? Do you know how he died?

I do, but I don't talk about it.

I know he was a young guy, in his mid-20's. He was an Army vet. He always wanted to be a donor, if anything ever happened to him. He was a good man; always cared about honor. People thought of him in an honorable way.

I've met his parents and all his siblings now. It's not like you see on the news, when you jump into the arms and cry. We didn't have that moment; we don't know each other.

It was a moment of gratitude for me and my wife. And it was a moment of caution because you're meeting somebody under the worst circumstance, for them.

I didn't want anybody to die. But someone has to die for you to get a heart. That's the bottom line.

And that person was 20 years younger than me, had his whole life ahead of him, had people who loved him, had a girlfriend. So he had his life.

And for that to happen was devastating. And for me to benefit from it is guilt-wrenching in many ways.

You have three young children. How did they handle everything?

The little ones didn't really know. They were 2. So they came and saw me in the hospital and said, "Hey, dad!" And we gave them ice cream.

Logan was 9, so he obviously was quite aware of it. I think he's worried it's going to happen again. He always asked me if I would "pass out." I think he meant to say, "Pass away."

I said to him, "We're trying not to." We don't want to get too deep with it, because I don't want to rob his childhood.

My point is, why worry about it? I've been through the hell of it; I'm not going to worry about it anymore. This is all golden; it's gravy.

What was your lowest point?

The hospital. I remember a couple of nights, FaceTiming with my kids, just crying, weeping afterward — just thinking, "This fucking sucks."

But the lowest point was right after I arrested for two and a half minutes, and then when I woke up, there's 20 people in my room, asking questions: 'What is today?" "What's your name?" They want to make sure that your brain didn't suffer damage.

That was a scary time. They said, "Listen, if that happens to you again, you're probably not coming back or you're going to be brain damaged or physically damaged to the point that you can't get a heart."

Realizing that you almost died weighs on you. I didn't leave that room for two days because I was afraid I was going to die. I was afraid to do anything.

What was your recovery like?

I recovered great. I was out of the ICU in 36 hours. I walked to my room — not easily. I don't remember much about ICU. I remember them pulling this fluid out of my chest and the pressure was intense and very painful. It's a rough go for a while.

Chest surgery is tough. For three months, you're really in big pain. Then once that goes away, you really start feeling great. But you can't get comfortable.

The grind is the biopsies. When you first get the transplant, they have to go into your neck, through your vein, every week to check for rejection.They take pieces of the heart out. And then it's every two weeks. Now it's every three months. You're getting blood work constantly.

I'm constantly reminded of what's going on. Every time I throw pills in my mouth, I remember why I'm doing it.

A lot of people don't take the time to take care of themselves. I treat this as my job. I have to take the medication. I have to stay healthy. I have to exercise, because it's my duty to this guy's heart. To Shawn. My duty to my family.

I was given this great chance. Am I going to piss it away, or am I going to work hard?

After the surgery, you're just grateful to be alive. After that, you're in recovery mode for half a year. Then when things get normal, you start thinking about your mortality again.

You have weird dreams. I'll constantly, once a week, have a dream about dying or something happening. But that's just what your brain is going to do to you.

If you wait for the other shoe to drop, you're not living. What am I doing to do, sit in a corner and not live? The whole point of this is to live.

What has the community's reaction been like?

Oh, my God — an outpouring of support. I didn't want it to be this "Ferris Bueller" thing: y'know, "Save Ferris" billboards.

Everybody knew I had heart problems, but when it got to the point that I had to go in, I didn't tell anybody why, publicly. It's a tough thing to straddle, your "celebrity" with the fact that you want to be private about something that's special to you and your family. Plus, it's not fair to my kids and to my wife to put them through all that.

When I got home and it was announced, I had, I'd say, at least 800 cards. Some people put money in. I'm like, "Don't give me your money." Just the outpouring is humbling, and you'll never be able to repay people for that.

Will you eventually need another transplant?

People CAN get a second transplant.

A lot of people die from other illnesses that are associated with the drugs that you take so you don't reject. Kidney failure, liver failure, cancer — all these things are possible with someone who's on the medication I'm on.

A kidney transplant could be in my future; leukemia; who the hell knows?

The best news about heart transplants is that people live longer with them now than they did 20 years ago, 30 years ago. So I'm in a great time.

Maybe in a decade the doctor says, "Hey, we're going to 3D-print you a heart." Maybe I do get another transplant when I'm 63. I'd definitely be willing to give it a shot.

I run 5K's now. I feel great. I feel like a new man.

A lot of people try to look at you with sympathy, [he whispers] "How are you feeling?" And I go, "Don't do that, because I'm great!" My Number 1 objective is to say, "Hey, this is awesome! What a great second chance I've got! Come on, look at me!"

All I know is that Shawn's heart is living in me, and it's great, and I'm just very grateful for the fact that I'm here.

More information about organ donation can be found at the Finger Lakes Donor Recovery Network, www.donorrecovery.org.

Scott Hetsko | heart transplants | University of Rochester Medical Center | heart disease

Latest in News

More by Christine Carrie Fien

-

Building up

Mar 29, 2017 -

Squeezing starts at GateHouse-owned Daily Record and RBJ

Feb 28, 2017 -

New purpose for controversial carousel panel

Feb 27, 2017 - More »