[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Diane Hampton remembers being a little girl and her grandmother taking her and her two sisters to Highland Park, where they would play around the “Children’s Pavilion” — a once grand focal point of the park that has been gone for nearly 60 years.

On a recent unseasonably warm spring day, Hampton stood where the pavilion once towered over her and everything else, just east of the reservoir, and recalled her grandmother standing on an upper level, taking snapshots of her grandkids having a blast.

“I just remember running up and down and around and around,” Hampton said. “I mean, these were my two older sisters I was playing with, you know. So they were probably just chasing me.”

That was more than 70 years ago. The historic pavilion was torn down in 1963 after years of neglect.

But a 20-year fundraising effort by the Highland Park Conservancy to resurrect the pavilion has county officials taking action.

The conservancy, a nonprofit park booster group, raised around $1 million for a new Children’s Pavilion and secured another $1 million in state grants.

In March, county legislators pushed the campaign over the finish line when they approved measures that made the pavilion a county project and authorized borrowing for its design and completion. The project is anticipated to cost $3.1 million, with county taxpayers expected to kick in up to $1.1 million.

Officials expect to start construction next year and project a 2024 opening.

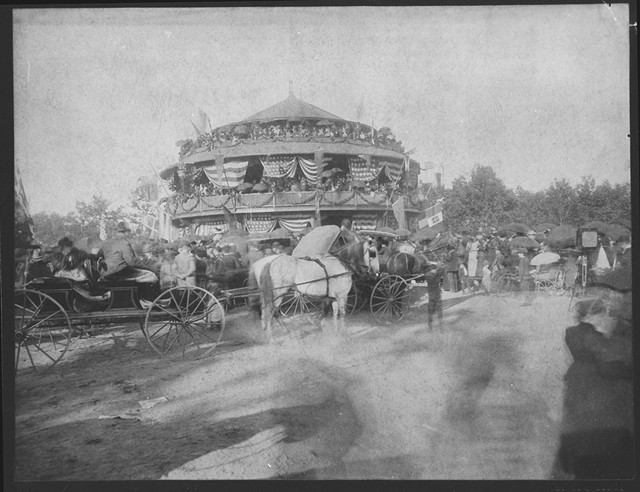

The original pavilion was an integral part of the plan for Highland Park, which was developed by the father of landscape architecture, Frederick Law Olmsted. The round structure, which cost $7,000, stood three stories tall, and was 62 feet in diameter, was a gift from the Ellwanger & Barry nursery.

Its dedication in September 1890 drew a crowd of 10,000 — Blue Cross Arena seats 13,000, for comparison’s sake — and the pavilion’s inscription stated that it was built in honor of Rochester’s children, who were increasingly choked by pollution from burgeoning industrialization.

“Childhood mortality was a terrible, terrible issue at the time,” said JoAnn Beck, president of the Highland Park Conservancy board as she walked near the pavilion’s historic footprint. “There were not antibiotics and the best that anybody could think of to mitigate this health crisis was fresh air and sunshine.”

In fact, Patrick Barry, one of the founders and namesakes of the nursery, had lost three of his sons to tuberculosis — they died between the ages of 17 and 20, respectively. Rochester Parks Commissioner George Elliott had lost two children to cholera, and two of Olmsted’s children also died in infancy.

Ellwanger & Barry also donated its 22 acres of nursery lands to the city for the establishment of Highland Park.

Bishop Bernard John McQuaid, who was a fervent proponent of establishing a public parks system in Rochester, praised the pavilion during his dedication remarks.

“Other large hearted and public spirited citizens will, in time, imitate and rival this first gift to the parks of Rochester,” McQuaid said. “A spirit of laudable pride will rise among them here, as it has risen elsewhere, to spend for the people’s instruction and improvement a portion of one’s accumulated wealth.”

The pavilion also fit directly with Olmsted’s driving philosophies. To him, parks were much more than decorative gardens or nature preserves. They drew on the land’s natural contours and on natural beauty over ornamentation.

Every element he designed in a park was intentional and served a purpose. He laid out Highland Park as a series of “rooms” that centered certain plants or features. To this day, anyone sauntering along the park’s formal and informal paths still passes from room to room.

But Olmsted also championed the egalitarian nature of parks. He believed that parks were a place for all people, and that they are part of the scenery and experience. To Olmsted, who suffered from depression and took pleasure in walking in nature, parks were places to soothe and refresh the mind and body.

He took that approach a step further in Highland by placing the pavilion on the park’s high point. He wanted to ensure that everyone in Rochester, poor or rich, had a place where they could freely soak in the spectacular view of treetops and rolling hills sprawling in the distance, some as far off as Bristol.

Beck said that the lilacs which have come to define Highland Park were planted to serve as a visual buffer against development happening near the park. She added that Rochester now has several tall buildings with their own impressive views, but they aren’t accessible to everybody. The new pavilion will restore an experience intended for all, Beck said.

Olmsted designed several parks in Rochester, including Genesee Valley Park and Seneca Park, but Highland is the most intact, Beck said. The new pavilion will bring the park back closer to its original plan, and it will also build on the original designer’s philosophy.

“We are struggling with social equity issues, we’re struggling with public health issues,” Beck said. “These are timeless issues and that is a timeless expression of community commitment to solving those issues. And it’s a profound expression of community values.”

“He had this grand vision of social equity, of everybody having equal access to beautiful places and, in doing so, creating a more just society,” Beck added. “And we never needed that more than we do today. That’s an evergreen principle.”

Jeremy Moule is CITY's news editor. He can be reached at [email protected].

On a recent unseasonably warm spring day, Hampton stood where the pavilion once towered over her and everything else, just east of the reservoir, and recalled her grandmother standing on an upper level, taking snapshots of her grandkids having a blast.

“I just remember running up and down and around and around,” Hampton said. “I mean, these were my two older sisters I was playing with, you know. So they were probably just chasing me.”

That was more than 70 years ago. The historic pavilion was torn down in 1963 after years of neglect.

But a 20-year fundraising effort by the Highland Park Conservancy to resurrect the pavilion has county officials taking action.

The conservancy, a nonprofit park booster group, raised around $1 million for a new Children’s Pavilion and secured another $1 million in state grants.

In March, county legislators pushed the campaign over the finish line when they approved measures that made the pavilion a county project and authorized borrowing for its design and completion. The project is anticipated to cost $3.1 million, with county taxpayers expected to kick in up to $1.1 million.

Officials expect to start construction next year and project a 2024 opening.

The original pavilion was an integral part of the plan for Highland Park, which was developed by the father of landscape architecture, Frederick Law Olmsted. The round structure, which cost $7,000, stood three stories tall, and was 62 feet in diameter, was a gift from the Ellwanger & Barry nursery.

Its dedication in September 1890 drew a crowd of 10,000 — Blue Cross Arena seats 13,000, for comparison’s sake — and the pavilion’s inscription stated that it was built in honor of Rochester’s children, who were increasingly choked by pollution from burgeoning industrialization.

“Childhood mortality was a terrible, terrible issue at the time,” said JoAnn Beck, president of the Highland Park Conservancy board as she walked near the pavilion’s historic footprint. “There were not antibiotics and the best that anybody could think of to mitigate this health crisis was fresh air and sunshine.”

In fact, Patrick Barry, one of the founders and namesakes of the nursery, had lost three of his sons to tuberculosis — they died between the ages of 17 and 20, respectively. Rochester Parks Commissioner George Elliott had lost two children to cholera, and two of Olmsted’s children also died in infancy.

Ellwanger & Barry also donated its 22 acres of nursery lands to the city for the establishment of Highland Park.

Bishop Bernard John McQuaid, who was a fervent proponent of establishing a public parks system in Rochester, praised the pavilion during his dedication remarks.

“Other large hearted and public spirited citizens will, in time, imitate and rival this first gift to the parks of Rochester,” McQuaid said. “A spirit of laudable pride will rise among them here, as it has risen elsewhere, to spend for the people’s instruction and improvement a portion of one’s accumulated wealth.”

The pavilion also fit directly with Olmsted’s driving philosophies. To him, parks were much more than decorative gardens or nature preserves. They drew on the land’s natural contours and on natural beauty over ornamentation.

Every element he designed in a park was intentional and served a purpose. He laid out Highland Park as a series of “rooms” that centered certain plants or features. To this day, anyone sauntering along the park’s formal and informal paths still passes from room to room.

But Olmsted also championed the egalitarian nature of parks. He believed that parks were a place for all people, and that they are part of the scenery and experience. To Olmsted, who suffered from depression and took pleasure in walking in nature, parks were places to soothe and refresh the mind and body.

He took that approach a step further in Highland by placing the pavilion on the park’s high point. He wanted to ensure that everyone in Rochester, poor or rich, had a place where they could freely soak in the spectacular view of treetops and rolling hills sprawling in the distance, some as far off as Bristol.

Beck said that the lilacs which have come to define Highland Park were planted to serve as a visual buffer against development happening near the park. She added that Rochester now has several tall buildings with their own impressive views, but they aren’t accessible to everybody. The new pavilion will restore an experience intended for all, Beck said.

Olmsted designed several parks in Rochester, including Genesee Valley Park and Seneca Park, but Highland is the most intact, Beck said. The new pavilion will bring the park back closer to its original plan, and it will also build on the original designer’s philosophy.

“We are struggling with social equity issues, we’re struggling with public health issues,” Beck said. “These are timeless issues and that is a timeless expression of community commitment to solving those issues. And it’s a profound expression of community values.”

“He had this grand vision of social equity, of everybody having equal access to beautiful places and, in doing so, creating a more just society,” Beck added. “And we never needed that more than we do today. That’s an evergreen principle.”

Jeremy Moule is CITY's news editor. He can be reached at [email protected].