[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

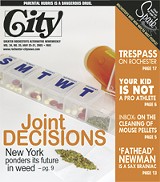

"Unfortunately, we have a mix of science and political science that makes it difficult to figure out what's going on."

That's how Gary Morrow, a clinical psychologist with Strong Health, describes the discussion going on now in Albany over whether or not to approve the use of marijuana for medical purposes.

If anything, Morrow's quote understates just how murky that particular combination renders the marijuana debate.

Morrow himself proves to be an example of just how tangled the issues can get. He's studied widely in the field of anti-emetics (translation: drugs that help keep you from throwing up), one of which is marijuana, and he's not in favor of legalizing the drug for medical use.

"It's not clear to me what this would do that we can't already do better," he says.

But even within his own institution, not everyone agrees. University of Rochester Medical Center and Strong Health Chief Operating Officer Peter Robinson supports the proposed law.

"There seems to be a body of scientific evidence that says there are some real benefits to be derived from medical marijuana," he says. "I'm pleased that the issue is on the table and being given a thoughtful consideration by the legislature."

The legislative discussion the two are talking about is the latest attempt to push a medical marijuana law through Albany. The proposal would allow doctors to prescribe marijuana to patients with life-threatening conditions for up to six months at a time after finding that all other options aren't as effective. (Unlike other drugs, doctors wouldn't be able to write their own prescriptions). Marijuana is typically used by patients with cancer --- especially to help keep food down during chemotherapy --- and those suffering AIDS-related wasting, glaucoma, and a few other chronic conditions.

Patients and their caregivers would be allowed to grow and possess a little more than two ounces, though they wouldn't be allowed to use it in public. They could also purchase marijuana from hospitals, clinics, state or county health departments, or non-profits set up for that purpose. Pharmacies would have the option of stocking it, and any of the providers would be allowed to grow it.

The law also has provisions to allow providers (though not individual patients) to purchase the drugs from law-enforcement stockpiles. All this would take place under the supervision of the state Department of Health, with whom each patient and provider would have to register (the registration fees are supposed to pay for the administrative costs to the DOH). The law sunsets after four years.

If New York passed such a law it would be the 13th state to do so. But in a way, all those laws are now on trial. A case before the US Supreme Court, Ashcroft v. Raich, could decide whether the federal government can enforce its own ban over state laws that permit medical use. The case was argued last fall and a decision could come at any time.

On the surface, the question of whether marijuana has any merits as a serious medicine seems to be one of simple scientific inquiry: Do enough of the right kind of peer-reviewed, replicable studies and you'll have yourself an answer.

But tell that to folks on both sides of the debate and the response you'll get will be a resounding "Exactly!"

Opponents of the bill say marijuana should be subjected to the same rigors as any other substance we allow doctors to prescribe.

Their pro-pot foes point to the federal government's draconian strictures on most marijuana research as a partial explanation for why that body of research doesn't exist.

In the absence of much hard scientific data, both sides tend to cite anecdotal evidence instead --- and criticize each other for doing so.

Stories of people who say marijuana was a last-ditch life-saver often dominate media coverage. Montel Williams, who uses it to combat multiple sclerosis and flew in from California to endorse the New York legislation, is a prime example. The drug alleviated his pain enough to allow him to attend a press conference in support of the bill, he told media.

That "I wouldn't be here without it" refrain is a familiar one; many patients who use marijuana say they turn to it after exhausting all the other options modern medicine has to offer. If the legislation passes, marijuana will remain a treatment of last resort. The bill requires doctors to try every other alternative first.

That's already an accurate description of the conditions under which illegal medicinal use of the drug takes place, doctors say.

"A lot of patients discover it on their own," Dr. Bill Valenti says. (Other doctors --- including those opposed to the bill --- say they've seen patients self-medicate with the drug after rejecting other medicines.) Valenti is the Founding Medical Director of the AIDS Community Health Center and Chair of HIV advisory panel for the Medical Society of the State of New York (MSSNY), one of the heavy-hitting organizations to endorse the new legislation. He's been working with AIDS patients in Rochester "since the beginning of the epidemic."

Valenti is the only doctor City Newspaper interviewed who acknowledged recommending the drug to patients, and he's seen his share of the anecdotal cases where the drug worked when others wouldn't. He doesn't expect a sharp increase in the number of people who are actually using the drug to fight illnesses, since it's already used mainly as a last resort.

"I would expect that to continue," he says. "I don't expect I'd become any more liberal about prescribing it."

Gary Morrow is one of those critics of the anecdotal defense of medical marijuana, disparaging it as pseudo-science.

"Some people find virtually everything useful," he says. "It doesn't mean that it's universally effective; that's where the science comes in."

But trying to explain away the drug's efficacy, Morrow himself resorts to something closer to storytelling than data-collecting:

"There's an aura about doing something against the law; you're fighting the system. The effect is not medicinal; it's psychological," he says. "Elderly folks who don't enjoy the effects of marijuana find it offensive and don't take the drug again."

When it comes to science, both sides claim it as an ally and cast doubts on the evidence their opponents cite.

"There are enough things available that are considerably better that I'm not sure why this keeps coming up," says Morrow. "It's not clear to me what this would do that we can't already do better." Like many others who oppose the bill, he cites the availability of the cancer drug Marinol, a pill that contains a synthetic form of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), one of marijuana's active ingredients.

Proponents of pot dismiss Marinol's availability as irrelevant to the entire medical-marijuana discussion. One such proponent is John Eadie. Eadie is a public policy advocate with StateWide Senior Action Council, but in a former life he was Director of the state Department of Health's Division of Public Health Protection, which oversees the Bureau of Controlled Substances. Marinol, he says, is specific to chemotherapy patients. It's slower-acting and doesn't work for everyone. And it was designed "before the AIDS wasting problem was identified and some other conditions," he says. "Marinol does not provide relief for all those."

That's something Valenti says he knows firsthand: "My experience is that I've seen people who don't respond to Marinol do to smoked marijuana."

Eadie explains the discrepancy between the effects of the pill and the joint by pointing out that there are plenty of cannabinoids besides THC in the smoke.

There are a few things about marijuana that all the medical professionals we talked to agreed on. They all agree that marijuana has some benefits for some people. And they all agree that inhaling smoke is not one of them. Despite arguing that it contains beneficial chemicals not found in the pill form, even proponents are uneasy about telling their patients to smoke something.

"I don't like the idea that people are inhaling smoke," says Eadie. "But that's the only way, until now, for people to get all the cannabinoids in marijuana." An inhalant spray form of the drug is being developed in Britain and Canada. Baking marijuana into foods or brewing it as tea are other popular options.

"It's a problem," Valenti says. "I would prefer that if we make it available to people, we would find ways to deliver it without smoke."

And both sides agree on the need for more research on marijuana. But where the bill's backers view it as a way to hasten the start of that research, detractors see it as a way of sidestepping the research and embracing medical marijuana carte blanche.

"It's a legal question right now. We haven't even gotten to the point where the scientific question can be studied," says Morrow. "It's a reasonable scientific question."

How will definitive research on pot be conducted? That question lies at the core of the issue, where the scientific and political debates converge.

If anyone knows about the mixing of science and politics over pot, it's Dr. Norm Wetterau. A family doctor who practices in Dansville and Nunda, Wetterau is the co-chair of MSSNY's psychiatric and substance-abuse committee, heads the American Society of Addiction Medicine's family practice working group, and is vice president of the New York Society of Addiction Medicine, where he works on public-policy issues. Though an opponent of the current legislation, he's more conflicted than any other doctor City interviewed and finds a lot to like in New York's proposed version of the law.

His opposition --- in addition to some serious concerns about pot's possible health risks --- is on the basis of principle.

"It should be treated like any other drug," he says. "We have a system for approving things. We should not be taking marijuana out of that system."

Wetterau's referring to the Food and Drug Administration's standard procedure of researching drugs.

"Are there people who can benefit from smoking? Probably. But should that mean we go around the system?"

Right now, on the basis of the US Constitution's Interstate Commerce Clause, the federal government enforces strict laws against the use, possession, sale, etc. of illegal drugs. That clause also forms the basis for the FDA's power to regulate all legal drugs, too. What happens when a critical mass of a state's citizens decides that the federal government isn't fulfilling its responsibilities? Can the state go around the FDA and approve a medicine themselves?

The medical marijuana case now before the US Supreme Court asks exactly that question. It's a question that's split conservatives, who tend to favor smaller central governments, between those who champion states' rights and those who are more concerned about illegal drugs. (The libertarian Cato Institute has long been an outspoken proponent of medical marijuana laws.)

"Maybe what the anti-marijuana people should do is try to release Vioxx in a state," Wetterau muses. (Manufacturer Merck pulled the arthritis drug from the market last year to avoid having the FDA do so after new research linked it to higher risks of strokes and heart attacks.) But in the end he comes back to defending the FDA's primacy, if only because it's the only uniform process out there for vetting drugs.

"Is a state prepared to undertake the cost of all that?" he asks. "Prescriptions should be a federal thing."

But proponents of the measure argue that by approving marijuana on a state-by-state basis, citizens send a message to Washington to get with it.

"One reason for states to pass legislation is to help send a message to the courts --- and the president and congress --- that this is what people want," says Manhattan Assemblymember Richard Gottfried, one of the legislation's primary sponsors. Gottfried's not worried about the impending decision from the high court.

"It is certainly possible that the Supreme Court will allow federal authorities to go to war against state laws," he says. But that only makes passing the bill more urgent.

"The more states enact laws like this the more likely the president or congress will turn that around."

Whether New York actually adopts a medical marijuana law will depend more on local politics than national trends or scientific studies. This year, perhaps for the first time ever, the outlook for Gottfried's bill isn't bad. The first time he introduced such a bill, in 1997, Senate Republican Majority Leader Joe Bruno vowed he'd kill it. Less than a decade later Bruno's reversed course and now proclaims himself an ardent supporter of medical marijuana. Observers speculate that a recent bout of prostate cancer may have helped to change his mind.

Gottfried wouldn't speculate on Bruno's about-face directly, but does say of individual legislators who back the bill "the sponsorship in many cases reflects experience with family or friends. That can be a very enlightening experience."

It may also explain why, as Gottfried puts it, "ideological support for this bill is about as broad as you can get." Half a dozen of the bill's co-sponsors in the assembly are conservatives.

Not everyone is happy with the legislation, though. Gov. George Pataki is reportedly opposed. Several calls to his administration's Department of Health weren't returned.

The state's influential Conservative Party has issued a scathing attack, with a position paper that opens with "The social engineers are at it again." The party accuses the bill's supporters of using terminal patients as cover for a back-door plot to legalize recreational use of the drug. The bill's sponsors and backers respond that their proposal employs strict guidelines and carries tougher penalties for using pot in violation of the health code than the state's penal code does for small amounts of marijuana. Even opponents like Wetterau admit that the bill is far narrower than propositions that have passed in California or Oregon, for example.

The Conservative Party's hard-line stance on the issue may place it outside the mainstream, even among its own partisans. In a major step forward for advocates, the legislation is being sponsored for the first time in the Senate by a member of the Republican majority, Hudson Valley's Vincent Leibell, who also carried the Conservative endorsement. Some of the bill's other sponsors and supporters also have ties to the party.

An informal polling of Rochester representatives also reveals support on both sides of the political aisle.

Republican (and Conservative) State Senator Joe Robach supports the measure and believes Bruno will push for it as well.

"I just don't look at this as a controversial issue at all," he says. "It's like anything else that a doctor prescribes."

Democratic Assemblymember David Gantt also offered a healthy prognosis for the bill.

"I believe it has legs," says Gantt, who added that his own mother was recommended the drug by her physicians.

"We have to recognize that if it has medical value we need to take it into consideration," he says. Fellow Assembly Dem Joe Morelle agrees.

"It clearly has benefits to people with long-term diseases," he says.

"This is a different year; we've done the budget on time, we're starting to look at public policy issues outside of the budget," Morelle says. "This is really the way it's supposed to work. We have the luxury of being able to focus on non-budget issues in the middle of May."

Speaking of Medical Marijuana, New York State

Latest in Featured story

More by Krestia DeGeorge

-

The last wild Finger Lakes

Jan 17, 2007 -

Designers get their turn at downtown

Jan 17, 2007 -

From the new governor: fighting words

Jan 10, 2007 - More »