[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

For nearly 50 years, the Out Alliance has aimed to cultivate an environment in greater Rochester in which people of all sexual orientations and gender expressions can reveal themselves safely and thrive.

These days, however, the agency is anything but thriving.

The agency’s executive director, Jeff Myers, resigned abruptly two weeks ago amid an internal investigation and its most recent public tax records suggest the organization ran an operational deficit two years ago that brought it to the brink of insolvency.

In recent days, unrest within the agency has surfaced, as employees have taken to social media to air grievances about management and to complain about losing access to internal computer software integral to their jobs.

“There are unprecedented problems we face right now,” Matt Burns, president of the agency’s board of directors, said in an interview.

Burns detailed a perfect storm of problems — expenses outweighing revenues, the departure of Myers, and the coronavirus pandemic curtailing donations, forcing the cancellation of the agency’s largest annual fundraiser in the Pride Festival, and slowing demand for revenue-generating services.

He said the agency was not immediately looking to replace Myers, who left the last week in May, and that the board was assessing its options to shape the Out Alliance of the future.

“Everything right now is unclear,” Burns said. “What we have to do right now is reign in the spending portion of the agency and do what we can do to increase the revenue so we can pay whomever we can.

“I would imagine that we would be looking for a person to be in charge of the agency, but the agency will look different than it does now.”

BORN OUT OF STONEWALL

Out Alliance, which was known for decades by its corporate name of the Gay Alliance of the Genesee Valley, was formed in 1973. Like so many gay advocacy groups, it was born out of the Stonewall riots of 1969 and subsequent grassroots activism.

In the case of Out Alliance, its roots took hold at the University of Rochester, where a group of students in 1970 formed the Rochester Gay Liberation Front. As the group’s membership grew to include people unaffiliated with the university, it renamed itself the Gay Alliance of the Genesee Valley and incorporated in 1973.

Since that time, Out Alliance has served as a prominent political, social, and cultural voice for the LGBTQ community, although it has faced criticism over the years for not equally representing people of color.

The agency has fought for equal rights, from solidifying domestic partnership laws to gay marriage, conducted social work, and launched education programs for schools and workplaces locally and nationwide.

In the process, it outgrew its tiny offices on the fifth floor of the Rochester Auditorium Theatre and moved to the community center with a storefront near Village Gate in the Neighborhood of the Arts that it occupies today.

Programming in recent years could be counted on to generate roughly $200,000 annually in revenue for the agency, financial records on file with the state Charities Bureau show. Grants and donations, along with annual Pride Festival fundraiser, rounded out the bulk of the revenue.

Financial statements show the organization, like a lot of nonprofits, generally broke even, with annual budgets ranging between $500,000 and $750,000.

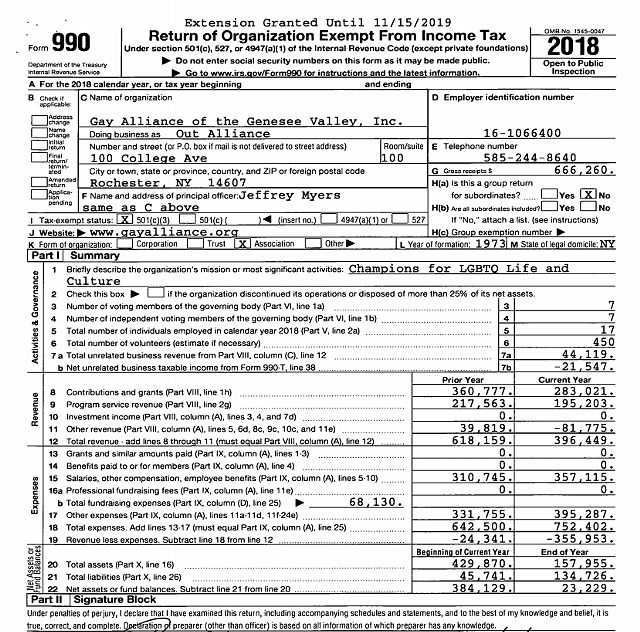

But in 2018, the last year for which records were available, the organization’s finances spun into a free fall.

FREE FALLING

Donations and program revenue had declined, and the organization reported losing an unprecedented $82,000 on fundraising efforts.

Burns attributed that loss to a monumental snafu at the Pride Festival that year, in which the credit card machines that were to be used to process entry fees to the festival at Cobb’s Hill Park malfunctioned.

With thousands of people clamoring to get in and the agency having no way to take their money, festival organizers threw up their hands and opened the gates to them for free.

By the end of the fiscal year, the agency had lost $356,000 — about half the agency’s operating budget and as much as it pays its staff of six full-time and four part-time employees in wages and benefits. The bottom lined showed it had $23,000 in net assets.

When the agency’s board released its annual report to the public for that year, dollar figures were notably absent.

Out Alliance’s bylaws call for the annual report to detail assets and liabilities and revenues and expenses.

The annual report for 2018 showed a dollar figure for contributions, but nothing else.

Revenues and expenses were broken down in a graphic that listed their percentages by category. For instance, 26 percent of revenues came from donors, and 35 percent of expenditures went to salaries.

Nowhere did the annual report note that the agency had lost so much money and so little on hand.

A BETTER PLACE

Burns, who, like most of nine members of the agency’s board of directors, joined the organization last year, said 2019 was a better year.

Financial statements for that year have not been made public yet, but Burns said revenue grew, operational expenses were reduced, and the Pride Festival made money. He added that a wealthy benefactor, whom he declined to name, died and bequeathed a six-figure sum to the organization in his will.

The board adopted a budget for the current fiscal year, which runs on a calendar year, that called for the spending plan to be reviewed quarterly and adjusted, if necessary.

“We were on track to a better place,” Burns said. “What happened was the pandemic. That put a wrench in all of those plans and brought us right back to the point where there simply isn’t enough revenue coming in to match the expenses going out. That’s the bottom line right now. That’s where we are and we’re not alone.”

INTERNAL OUTRAGE ONLINE

This week, Out Alliance employees took to social media to complain.

Kristin Wiggall, the agency’s database administrator, described in a lengthy Facebook post that the agency was “in trouble,” how there were multiple “whistleblower complaints,” and how she was stripped of access to the database without explanation after she spoke to board members about her concerns.

“Don’t stand for it. Email the board, call them,” she wrote. “Demand a voice. Demand that we be given the opportunity as staff and community to save the agency. . . . This is YOUR agency. This is OUR agency.”

Wiggall declined to be interviewed and referred a reporter to her post, in which she also told of another employee losing his administrative privileges to manage Out Alliance’s Facebook page.

Burns acknowledged that some employees had lost some duties. He said the measures were not intended to be punitive, but rather to pause the internal workings of the agency so board members could get a sense of where the agency stood.

“We need to take a snapshot of where the agency is in order to make decisions,” Burns said.

Burns also acknowledged that some employees had filed complaints but declined to provide specifics, citing a desire to protect the whistleblowers.

He said the complaints were related to management and had prompted the board to investigate Myers, the former executive director. He added, though, that the board had not made a finding and did not ask Myers to resign.

Myers, who became the executive director in 2018 when his predecessor, Scott Fearing stepped down, issued a statement Wednesday in response to a request for an interview.

His statement read that he was informed May 19 that the board had received multiple complaints against him for discrimination and that he was suspended without pay until further notice.

Myers said he was told there would be an internal investigation in which all Out Alliance employees would be interviewed, but that the probe was never concluded.

He added that he was never told the specifics of the allegations against him and denied any wrongdoing.

"On May 28, I resigned my position as executive director of the Alliance because it was evident to me that their decision to terminate me was a foregone conclusion," Myers said in his statement.

"There was a lack of due process, and a complete disregard of my significant contributions to the Alliance," he went on. "During my time as executive director, I conducted myself with professionalism and integrity at all times relevant hereto."

"It is my hope that regardless of these circumstances that this vital agency, the Out Alliance, survives and thrives," he said.

Bess Watts, a longtime gay rights activist and president of Pride at Work AFL-CIO Rochester Finger Lakes Region, an organization for LGBTQ and allied union members, said it was critical for the community that Out Alliance work out its problems.

“It would be great if people talk with each other instead of about each other or against each other,” Watts said. “It’s so important that the agency be healthy and exist,” she added.

Asked if the agency would continue to exist, Burns said, “Yes.”

“I can’t imagine a Rochester without Out Alliance,” Burns said. “In one way, shape, or form, even if the worst case scenario comes true and we have to take a break for a while, there will be a rebirth of the agency and we will grow again.”

Includes reporting by Jeremy Moule and Rebecca Rafferty.

David Andreatta is CITY’s editor. He can be reached at [email protected].

These days, however, the agency is anything but thriving.

The agency’s executive director, Jeff Myers, resigned abruptly two weeks ago amid an internal investigation and its most recent public tax records suggest the organization ran an operational deficit two years ago that brought it to the brink of insolvency.

In recent days, unrest within the agency has surfaced, as employees have taken to social media to air grievances about management and to complain about losing access to internal computer software integral to their jobs.

“There are unprecedented problems we face right now,” Matt Burns, president of the agency’s board of directors, said in an interview.

Burns detailed a perfect storm of problems — expenses outweighing revenues, the departure of Myers, and the coronavirus pandemic curtailing donations, forcing the cancellation of the agency’s largest annual fundraiser in the Pride Festival, and slowing demand for revenue-generating services.

He said the agency was not immediately looking to replace Myers, who left the last week in May, and that the board was assessing its options to shape the Out Alliance of the future.

“Everything right now is unclear,” Burns said. “What we have to do right now is reign in the spending portion of the agency and do what we can do to increase the revenue so we can pay whomever we can.

“I would imagine that we would be looking for a person to be in charge of the agency, but the agency will look different than it does now.”

BORN OUT OF STONEWALL

Out Alliance, which was known for decades by its corporate name of the Gay Alliance of the Genesee Valley, was formed in 1973. Like so many gay advocacy groups, it was born out of the Stonewall riots of 1969 and subsequent grassroots activism.

In the case of Out Alliance, its roots took hold at the University of Rochester, where a group of students in 1970 formed the Rochester Gay Liberation Front. As the group’s membership grew to include people unaffiliated with the university, it renamed itself the Gay Alliance of the Genesee Valley and incorporated in 1973.

Since that time, Out Alliance has served as a prominent political, social, and cultural voice for the LGBTQ community, although it has faced criticism over the years for not equally representing people of color.

The agency has fought for equal rights, from solidifying domestic partnership laws to gay marriage, conducted social work, and launched education programs for schools and workplaces locally and nationwide.

In the process, it outgrew its tiny offices on the fifth floor of the Rochester Auditorium Theatre and moved to the community center with a storefront near Village Gate in the Neighborhood of the Arts that it occupies today.

Programming in recent years could be counted on to generate roughly $200,000 annually in revenue for the agency, financial records on file with the state Charities Bureau show. Grants and donations, along with annual Pride Festival fundraiser, rounded out the bulk of the revenue.

Financial statements show the organization, like a lot of nonprofits, generally broke even, with annual budgets ranging between $500,000 and $750,000.

But in 2018, the last year for which records were available, the organization’s finances spun into a free fall.

FREE FALLING

Donations and program revenue had declined, and the organization reported losing an unprecedented $82,000 on fundraising efforts.

Burns attributed that loss to a monumental snafu at the Pride Festival that year, in which the credit card machines that were to be used to process entry fees to the festival at Cobb’s Hill Park malfunctioned.

With thousands of people clamoring to get in and the agency having no way to take their money, festival organizers threw up their hands and opened the gates to them for free.

By the end of the fiscal year, the agency had lost $356,000 — about half the agency’s operating budget and as much as it pays its staff of six full-time and four part-time employees in wages and benefits. The bottom lined showed it had $23,000 in net assets.

When the agency’s board released its annual report to the public for that year, dollar figures were notably absent.

Out Alliance’s bylaws call for the annual report to detail assets and liabilities and revenues and expenses.

The annual report for 2018 showed a dollar figure for contributions, but nothing else.

Revenues and expenses were broken down in a graphic that listed their percentages by category. For instance, 26 percent of revenues came from donors, and 35 percent of expenditures went to salaries.

Nowhere did the annual report note that the agency had lost so much money and so little on hand.

A BETTER PLACE

Burns, who, like most of nine members of the agency’s board of directors, joined the organization last year, said 2019 was a better year.

Financial statements for that year have not been made public yet, but Burns said revenue grew, operational expenses were reduced, and the Pride Festival made money. He added that a wealthy benefactor, whom he declined to name, died and bequeathed a six-figure sum to the organization in his will.

The board adopted a budget for the current fiscal year, which runs on a calendar year, that called for the spending plan to be reviewed quarterly and adjusted, if necessary.

“We were on track to a better place,” Burns said. “What happened was the pandemic. That put a wrench in all of those plans and brought us right back to the point where there simply isn’t enough revenue coming in to match the expenses going out. That’s the bottom line right now. That’s where we are and we’re not alone.”

INTERNAL OUTRAGE ONLINE

This week, Out Alliance employees took to social media to complain.

Kristin Wiggall, the agency’s database administrator, described in a lengthy Facebook post that the agency was “in trouble,” how there were multiple “whistleblower complaints,” and how she was stripped of access to the database without explanation after she spoke to board members about her concerns.

“Don’t stand for it. Email the board, call them,” she wrote. “Demand a voice. Demand that we be given the opportunity as staff and community to save the agency. . . . This is YOUR agency. This is OUR agency.”

Wiggall declined to be interviewed and referred a reporter to her post, in which she also told of another employee losing his administrative privileges to manage Out Alliance’s Facebook page.

Burns acknowledged that some employees had lost some duties. He said the measures were not intended to be punitive, but rather to pause the internal workings of the agency so board members could get a sense of where the agency stood.

“We need to take a snapshot of where the agency is in order to make decisions,” Burns said.

Burns also acknowledged that some employees had filed complaints but declined to provide specifics, citing a desire to protect the whistleblowers.

He said the complaints were related to management and had prompted the board to investigate Myers, the former executive director. He added, though, that the board had not made a finding and did not ask Myers to resign.

Myers, who became the executive director in 2018 when his predecessor, Scott Fearing stepped down, issued a statement Wednesday in response to a request for an interview.

His statement read that he was informed May 19 that the board had received multiple complaints against him for discrimination and that he was suspended without pay until further notice.

Myers said he was told there would be an internal investigation in which all Out Alliance employees would be interviewed, but that the probe was never concluded.

He added that he was never told the specifics of the allegations against him and denied any wrongdoing.

"On May 28, I resigned my position as executive director of the Alliance because it was evident to me that their decision to terminate me was a foregone conclusion," Myers said in his statement.

"There was a lack of due process, and a complete disregard of my significant contributions to the Alliance," he went on. "During my time as executive director, I conducted myself with professionalism and integrity at all times relevant hereto."

"It is my hope that regardless of these circumstances that this vital agency, the Out Alliance, survives and thrives," he said.

Bess Watts, a longtime gay rights activist and president of Pride at Work AFL-CIO Rochester Finger Lakes Region, an organization for LGBTQ and allied union members, said it was critical for the community that Out Alliance work out its problems.

“It would be great if people talk with each other instead of about each other or against each other,” Watts said. “It’s so important that the agency be healthy and exist,” she added.

Asked if the agency would continue to exist, Burns said, “Yes.”

“I can’t imagine a Rochester without Out Alliance,” Burns said. “In one way, shape, or form, even if the worst case scenario comes true and we have to take a break for a while, there will be a rebirth of the agency and we will grow again.”

Includes reporting by Jeremy Moule and Rebecca Rafferty.

David Andreatta is CITY’s editor. He can be reached at [email protected].