Perspectives: Jean Carroll

The former YWCA president on white Americans, race, and women in poverty

By Tim Louis Macaluso

[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Jean Carroll, who stepped down from the presidency of the YWCA of Rochester and Monroe County at the end of April, has been a champion of women's issues for more than 30 years, especially those of poor women of color.

She'd be the first to say she doesn't have all the answers to the problems those women face. But Carroll's personal and professional lives have overlapped in ways that have given her insight into such issues as racism, sexism, and poverty.

In three decades with the YW, she led the organization through some particularly tough times: cutting expenses and steering it away from its older, image as a charity and aiming it squarely toward social change. Out went money-drains like the YW's swimming pool, with its high heating costs, and Camp Onanda near Canandaigua, in favor of more housing and services for women. And the local YW embraced the YWCA's national "Stand against Racism" campaign.

Carroll is married to Ben Douglas, an African-American who has served on both the Rochester school board and City Council. Their long marriage produced their two bi-racial children, both of whom are now grown.

Carroll tends to talk about racism as if it were an invader, an interloper in the American subconscious that can disguise itself in a multitude of ways – and can even leave the impression that it doesn't exist. Though she says she and Douglas were fortunate in that both of their families have supported their marriage, she developed a keen sense of the severe damage racism causes from seeing how it affects the people she loves most. That doesn't make her an expert on racism, she says, but it strengthened her resolve to face it.

In a recent interview, Carroll talked at length about the devastating impact of poverty and racism on women of color in Rochester and the barriers those women face in getting out of poverty. And she talked about finding her own voice, as a white woman, to advocate on their behalf.

The following is an edited version of that interview.

CITY: What concerns you most when you reflect on your work with women, particularly women of color? What have you seen them struggling with most?

CARROLL: The issue many women of color in Rochester are dealing with is poverty. And along with poverty, there's the stress from living in poverty.

Poverty is not the same for women of color as it is for white women. There are so many more barriers for women of color, and a lot of those barriers have to do with the environment they find themselves confined to: raising children on their own, poor housing, challenges with evictions, domestic violence, and sexual abuse.

The trauma that comes from living in that type of environment wreaks havoc on your health and on your nervous system. We look at people and say that they're resilient and they can survive this if they want to. But most people don't have multiple traumas coming at them at the same time.

Maybe you've found a place to live where the person who was abusing you can no longer get to you, but now you're having trouble paying the rent. So what happens? You get evicted at the end of the month. Where do you go so that you don't end up homeless? Maybe it's back to the person who was abusing you.

There are just so many challenges for women of color living in poverty. And I don't know if it's a lack of understanding or a lack of will in seriously addressing it. There's still a lot of blaming that goes on and a lack of listening to the voices of women in poverty to understand why they are there.

I think the barriers to success are not things the women we serve have a lot of control over. The barriers to success are often people who are in positions of privilege but lack the knowledge and skills to engage with women who are different from them.

If it was just up to the women to make some changes in their lives, don't you think it would have happened a long time ago? It's not that they don't put in the effort, time, desire, and hard work to change their lives. That's a myth. They do, and they keep trying and trying.

But so often people in power are like: Well, you know, it doesn't have any effect on me, so, I'm sorry, but....

Here's the thing: It definitely does have an effect on everyone. It impacts the broader community. I'll give you an example. You hear employers lament all the time: "We can't find people to fill these jobs that we have."

Well, why is that? Maybe we have to figure out how to create a path for women in poverty that works for them. How do we create more win-wins for women in poverty and businesses so that their economic situations get healthier and are sustainable?

Some people will hear that and say, Look, there are consequences to making bad decisions. You made the decision to get pregnant at 16 and not to finish school. Why should I pay for your mistake?

I would say that the person making that statement should think back to when they were 16 and ask themselves how capable they were in making those kinds of decisions. What was around them that influenced them to make appropriate decisions? What kind of environment did they live in? What role models did they have? But more importantly, what did they see as their future?

Very often, the young women you might say "made a choice" to get pregnant were experiencing something else: They didn't see a different future for themselves.

At 16, they've already experienced a great deal of trauma. They may be homeless. They may be living on someone's couch. Their mother may be suffering from addiction. So they're looking around and thinking, This is my life. They don't see a way out.

It's not a decision about doing what's right. There's no strategy to it.

All women are sold the bill of goods about Prince Charming: There's a man that's coming along to rescue them. And these women may not have any experience with what a healthy relationship is.

When your boyfriend is making you feel good because you're his and being his means that he gets to control everything you do, that's not a healthy relationship. If you don't understand the power dynamics in a relationship, that can lead to unintended things like a pregnancy at 16.

Understanding what a healthy relationship is means having the confidence to say to yourself that you are worthy, and you deserve someone who respects you. You deserve someone who will not put you in a situation where your future is impaired because you could become pregnant at 16.

A lot of this is about having someone to talk to about these types of things, which is what we do at the YW. It's about having a different perspective to help you make the best decisions for you.

If you compare this to the #MeToo movement: you have adult professional women in jobs who for so many years have put up with sexual harassment and sexual abuse because they felt it would endanger their future.

Now imagine being 16 and having thE strength and courage to call out people who may be endangering your future. Then consider what happens if you're a young woman of color.

If you say no, almost anything can happen. We've had instances at the YWCA where the mother's boyfriend was sexually abusing that 16-year-old girl, and he was the father of her child.

What do you do then? How do you handle that? Where will you live? It gets very complex when you have no resources.

Many people are inclined to blame poor people for being poor: "My family was poor, too. But I pulled myself up by the boot straps, so why can't they?"

People need to reflect on who helped them. Was it your parents? Yes, but was it only your parents? Was it your Girl Scout troop? Was it the lady at the end of the block who had the resources to pay you to mow her lawn? There were a lot of people in your life that contributed to your success.

People who think they pulled themselves up by their bootstraps don't recognize that often white privilege was playing a role. And white privilege has been operating for hundreds of years in this country.

That has not been the case for people of color. There are a lot of things people can change. You can change your hairstyle. You can change the way you dress. But you can't change the color of your skin. It doesn't matter whether you're poor or rich. People who are not white are called upon to prove themselves every day at a level that white people have never had to do.

My parents were both Irish immigrants, and they had a fourth-grade and eighth-grade education, but they were white. They spoke English. Their kids were not without challenges, but they were successful.

Unfortunately, because of our history, people of color today experience constant micro-aggressions. I know a young woman, a professional woman, a woman of color, who went with her family to a travel agency to plan a vacation. When they walked into the travel agent's office, the agent said to them, "I think it would be best if you looked online for vacation opportunities. You can get some really good deals that way."

There was an immediate assumption, without even taking a moment to talk to them, that they couldn't afford a vacation because they were people of color. They were a successful family, but because they were a family of color they were automatically seen as low income and not worthy of the agent's services or time.

This unconscious bias is all around us, and it's so much a part of the water that we drink. It's not something white people have to think about. It's part of what life is in America, and it's become normalized. But it's not normal.

Being married to someone who is African-American has given me a bit of a window into understanding. And having two children of mixed race also has been part of my experience.

When the national office called upon us to use the "Eliminating Racism and Empowering Women" logo, that was a conscious decision at the national level. They felt that if we were going to empower all women, we also had to be dedicated to eliminating racism.

I was very fearful about taking that on. I felt like, here we are doing this great work, and at least half of the women we serve at the YWCA are women of color. So I am thinking: We're already doing it. We have housing. We have services to help teens. Aren't we eliminating racism by providing the services that women need?

And the answer that I got from women of color was, "No, that is not enough."

These women were saying, We are not simply a charitable organization. We need to be an organization that's committed to social change.

I really did think to myself, what do I know about it? Yes, I knew something, but really, what do I know? I'm a white woman. How do I begin to articulate the experience of a person of color?

And I was really nervous about coming back to Rochester and even putting this new logo on my building, because I was thinking that there are organizations out there like the NAACP, Action for a Better Community, and the Urban League that would see it and say to me, "Who do you think you are?"

But they didn't do that. Maybe it was because I've always been conscious of having more women of color on my board of directors to help build relationships with these organizations.

I was still having this concern, OK, what do I say about this? There is a book, "Witnessing Whiteness," by Shelly Tochluk. She's a teacher, and she really hit the nail on the head in terms of where the critical issue of race is in this country. And she raises these questions: What can white people do? What is the role of white people in advancing racial equity?

Her book gave me a framework with which to move forward. She helped me to articulate what I think about this.

Many white people would almost reflexively agree with your anti-racism message, but how dO you know whether you're really changing attitudes? For instance, what happens when the black family moves in to the house next door?

Or what happens to the young black man who comes into your store? Or you're trying to fill a job opening and you're looking at resumes and the name on the resume is Shekeena; what happens?

There are many approaches to this, but the approach we're taking is educational, where people can come together and learn together across race and ethnicity.

How often do we really have the opportunity to engage in a conversation about race with somebody who is of a different race? How do you even begin that conversation? Race is one of those things we don't talk about, like religion, politics, and how much money you make. What we're attempting to do is to get that conversation about racism going across boundaries, because we are so segregated.

Even if you have people of color in your workplace, those kinds of conversations from a white person's standpoint are fraught with landmines. It's fearful going into that territory, because often you lack knowledge about "the other."

How do you get knowledge about the other unless you seek that out? How are you going to interact with people in your workplace when you don't really have the knowledge and skills to do that?

We decided we would provide opportunities for people to do that. It's not something new. When Bill Johnson was mayor, he created the Bi-racial Partnership in the early 90's. But it wasn't sustained.

It's about building awareness. Many people don't know about our real history. You hear people say, "Well, slavery and all that happened a long time ago. We're past all of that, aren't we?" And the answer is, of course, no, we're not.

The Federal Housing Authority was set up after the Great Depression to help people buy a home. It was especially helpful to the GI's after World War II. But efforts were also made to make it difficult for people of color to have access to those loans.

So when people think about their own personal history, they can relate to the fact that maybe their parents or grandparents were beneficiaries of these low-interest home mortgages and home ownership. And because they had that, they were able to build wealth and transfer it to their children and grandchildren.

The more you can help people see how their family was treated differently, the more likely they are to understand racial inequity. Sure, their families may have had hardships, but they were still treated differently because they were white.

Becoming knowledgeable of authentic and honest history is critical to building understanding about racism, but it's not enough. You still have to build your skills about how to have this conversation.

For instance, do you interrupt someone when they say something that's racist? Do you say, "That's a racist comment," and put them on the defensive?

This whole thing requires a lot of courage. It requires humility.

When we came out with our new logo "Eliminating Racism and Empowering Women," some board members said: "That's so negative. Can't we say something like 'Encouraging Diversity'?"

No, it's not same thing.

That internal work is still an ongoing challenge for the organization itself. That's not a criticism. That's to say that all of this is an ongoing process. It's never finished.

What was it like for you and Ben to be together when you got married?

Honestly, we were very fortunate. Maybe we lived in our own little bubble. But we both had families who were very accepting, and we knew that wasn't the case for everyone.

We've had experiences that weren't positive. And I have experienced some of the challenges that people of color experience because I was with a person of color.

What's funny about this were my first reactions; I did what most white people do. We'd be waiting in line in a restaurant and people would get seated ahead of us, and Ben would groan. He would say, "I'm really getting annoyed with this," and I would say "Well, maybe they had reservations. There's probably some other reason for it."

He's had many experiences of being overlooked and treated as less than because of his skin color. Part of this was a learning experience for me, because we're taught that every achievement in life is about individual merit. Well, that's a lot of crap. I know that's true from just his day-to-day life and some of his work experience as well.

I have a much greater understanding of what happens in the workplace than I ever would have had if I wasn't married to him. I have a great appreciation not only for the micro-aggressions that happen, but the outright discriminatory practices that continue to play out.

What was it like to walk into a store with your bi-racial children? Did people think they were your children?

No, not all the time. I remember once we were at Hersey Park, and we're doing the usual family thing with the kids, and we were waiting in line. And the guy in front of me saw me and said, "Oh, are they Fresh Air kids?"

I had this great dream of one day starting a multi-racial child care center at the Y, and it was just so hard to do, because a child care center is really a privilege that is in most cases limited to people who are middle income and above. And if they are middle income and above, are they willing to have their children be with children who are low income? No.

People will say it's a class issue, but that's just a way of making themselves feel comfortable. This way they don't have to have the real conversations, and they don't have to do the hard learning that's involved in understanding racism.

We need to turn the table and be able to go directly to that conversation and ask: "How did so many people of color end up being low income? Why is that? Why is there such a disproportion?"

And no, it's not because they aren't working hard.

A YWCA legacy: supporting women

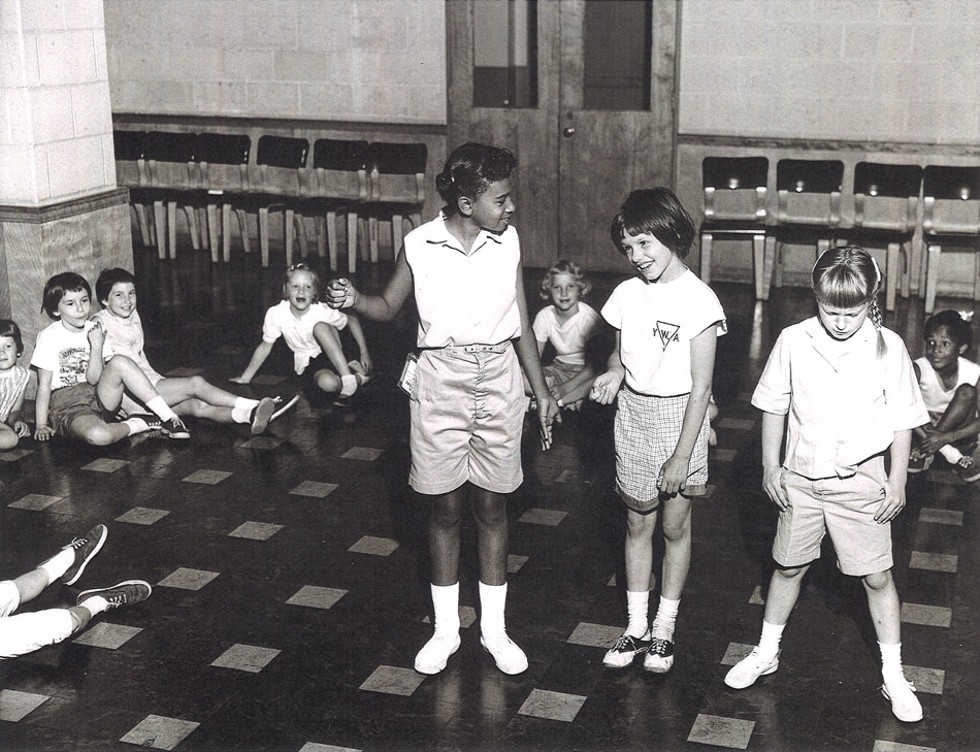

Many people associate the YWCA with health and fitness, but that's not how it started. "Since it was founded in 1883 in Rochester, it's always been about empowering women," says Jean Carroll, who recently stepped down from leading the Rochester organization.

Like the YMCA, the YW started during the Industrial Revolution. And both supported people who moved from rural areas to cities in search of work.

"Both organizations played a big role in that effort," Carroll says. "So a lot of this was about finding housing when you came to the wicked city."

The other part of the organizations' early effort was helping the new urban arrivals develop jobs skills, Carroll says, because many people were trying to transition from farm work to factory or office work.

Given the country's history with racism, many YWCA's were on the front lines of striving for racial equity. The YWCA cafeterias were among the first places where women of color were served in public areas, Carroll says.

In the mid-20th century, the Y offered dorm-style rooms to women. But by the late 1960's, the Rochester Y had to reexamine its mission and the services it offered women. There was a steady increase in poverty in Rochester during her tenure at the Y, Carroll says.

As the Y has responded to community needs, housing has become one of its main services. The Y had 42 housing units in its downtown facility when Carroll assumed leadership. Now there are 146 units, some in the downtown Y and some in two others off site, serving women who need emergency housing due to issues like domestic violence and addiction recovery.

And, Carroll says, "We now see more families."

The Rochester Y also provides school programs for teens and young adult women. One of them, "Be Prepared, Be Responsible," is often part of high school sexual health classes, but the programs aren't limited to school settings, Carroll says.

Speaking of...

-

More than half of US students are from poor households

Jan 20, 2015 -

Rochester's viral profile

Feb 12, 2014 -

Two Rochesters and two Americas

Dec 10, 2013 - More »