[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

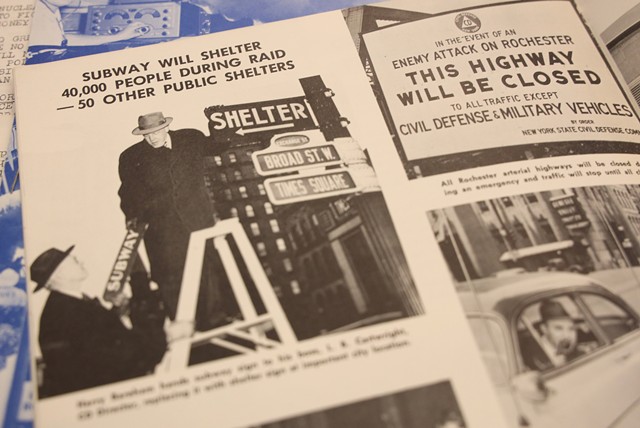

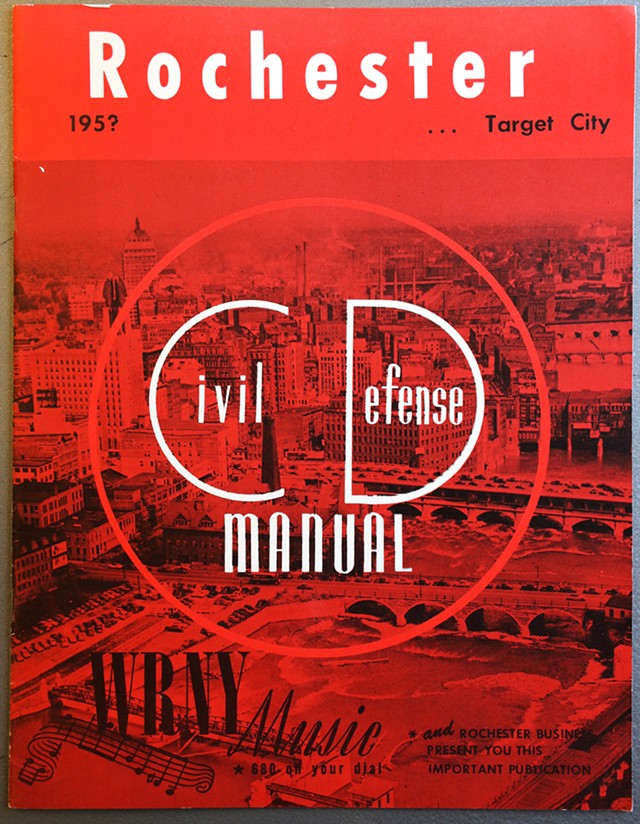

Sixty years before Russian President Vladimir Putin raised the specter of nuclear war with his invasion of Ukraine — and President Joe Biden told Americans not to worry about it — iconic yellow and black signs marked “Fallout Shelter” began popping up in the streets of Rochester.

They were affixed to hundreds of buildings in and around the city — schools, offices, apartment complexes, warehouses — that the Army Corps of Engineers had determined offered the right amount of “radiation shielding.”

Back then, it was the Russians and the Cuban Missile Crisis that had pushed the Cold War simmer to a boil, and those yellow and black metal signs were seen as an ominous emblem of the times.

Today, those signs are seen as kitschy relics of a different era, although a new poll conducted by The Associated Press and the NORC Center for Public Affairs Research shows that close to half of Americans say they are "very concerned" that Russia would directly target the U.S. with nuclear weapons.

The few signs still hanging around have been corroded by rust and time, and the spaces they advertised — once stocked with foodstuffs, first aid kits, canned water, toilet paper, and bedding — were long ago repurposed into storage rooms for who knows what.

They cling to places like the Ohio Street entrance to East High School, the back of a former State University at Brockport building on Bragdon Place downtown, and the brick façade of Turcott’s Taproom on Monroe Avenue. One sign on the side the Salvation Army building on Liberty Pole Way still notes the capacity — 590 souls.

There is no telling precisely how many public fallout shelters existed in Monroe County. A county spokesperson acknowledged that the county stopped maintaining public shelters after what was known as the federal Office of Civil Defense was dissolved in the 1970s, and that a list of shelter locations has been lost to time.

Archives of news articles and Civil Defense newsletters that were issued quarterly offer the best estimates of the number of shelters. By those accounts, there were anywhere from 400 to 600.

A Civil Defense newsletter from January 1964 read that there were 390 “fully-stocked shelters” in the county that could sustain 192,130 people for two weeks. Ten years later, the county’s Civil Defense shelter officer told the Democrat and Chronicle there were 584 shelters with enough room for 376,534 people.

“And you can rest assured that if the bomb was dropped tomorrow, they’d be ready,” the newspaper reported.

Tomorrow came and went. Two years later, the county Civil Defense agency determined that most of the food inside the shelters was rancid, a fact it reportedly learned after “derelicts had gotten into shelters and became sick from eating the food.” By 1978, the office had been disbanded and the shelters were cleared out in a massive public undertaking.

The fallout shelter initiative in Rochester hit its stride after Gov. Nelson Rockefeller — a zealous proponent of shelters who built his own $3.5 million bunker in Albany — launched a state shelter program in 1960.

Rochester, it was reported often and urgently during the era, was a target due to its technology sector led by Eastman Kodak Co. and Xerox.

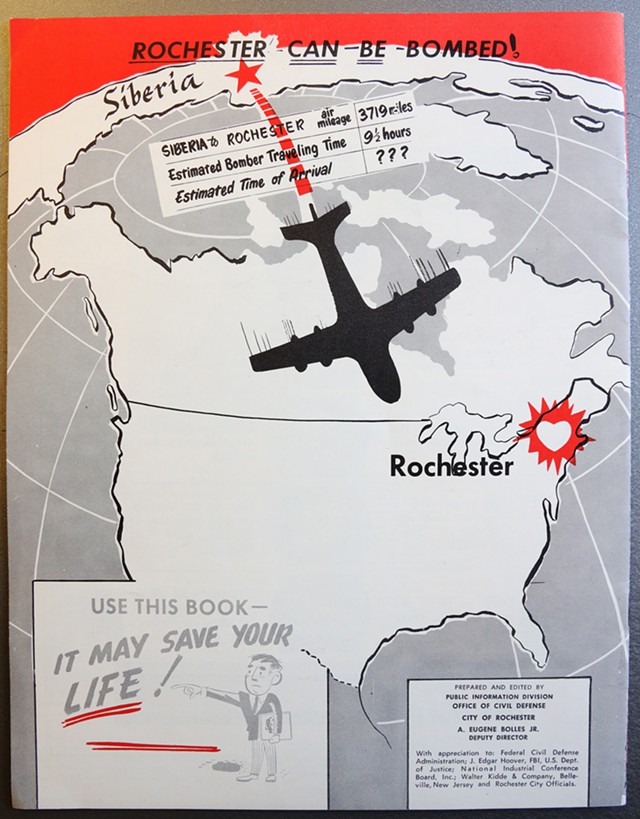

The back cover of a Civil Defense manual on do-it-yourself home fallout shelters issued to county residents reinforced the message. “ROCHESTER CAN BE BOMBED!” screamed the headline over a cartoon image of a shadowy bomber plane spanning the globe 3,719 miles from Siberia to Rochester. “Estimated Time of Arrival: ???”

“It was a really scary time and I remember being afraid of the Russians,” said Kate McBride, 68, who recalled building a shelter in the basement of her childhood home on Nunda Boulevard with her father, Jim Borden, in the early 1960s.

She described her father as a Kodak engineer and a World War II veteran who was stationed in occupied Japan and witnessed firsthand the devastation of the atomic bomb.

“I can remember putting the cement between the cinder blocks and helping him build it,” she said. “He took it on as a project and he wanted to protect his family.

“You have to put this in historical context,” she went on. “You think about it now and you think how is that really going to protect anybody? But at the time, I think people took it seriously because the government really took it seriously.”

As Cold War tensions eased, her family’s fallout shelter, which she recalled as being 8 feet-by-8-feet and outfitted with bunk beds and shelves stocked with food and other supplies, became a place for her and her friends to play and sleep.

In addition to spending millions on carving out space for public shelters, the state fallout shelter program offered property tax incentives to homeowners who prepared for a Soviet attack.

There are still nine houses on the city tax roll that receive a tax abatement of between $150 and $200 for having a fallout shelter. One of them is McBride’s childhood home.

Another is around the corner on Hartsen Street that has belonged to Alison and Jovan Livada since December 2019.

“When we toured the house, the realtor was like, ‘I think there may be a bunker in the backyard,’ and we were like, ‘No way! What?’” she said.

The shelter had been filled at some point before the Livadas bought their home and, as far as they can tell, its remaining underground cavities are today a refuge for groundhogs and squirrels. The only evidence that something is, or once was, underneath their backyard lawn is a square brick fire pit that juts from the grass like a chimney.

“It’s always been a joke to just say to friends, ‘You know, when World War III happens, you can help us dig it out, grab your shovel and come on over,’” Livada said with a laugh as she inspected the ground. “We don’t know what’s underneath here, but we’re ready to go.”

David Andreatta is CITY's editor. He can be reached at [email protected].

They were affixed to hundreds of buildings in and around the city — schools, offices, apartment complexes, warehouses — that the Army Corps of Engineers had determined offered the right amount of “radiation shielding.”

Back then, it was the Russians and the Cuban Missile Crisis that had pushed the Cold War simmer to a boil, and those yellow and black metal signs were seen as an ominous emblem of the times.

Today, those signs are seen as kitschy relics of a different era, although a new poll conducted by The Associated Press and the NORC Center for Public Affairs Research shows that close to half of Americans say they are "very concerned" that Russia would directly target the U.S. with nuclear weapons.

The few signs still hanging around have been corroded by rust and time, and the spaces they advertised — once stocked with foodstuffs, first aid kits, canned water, toilet paper, and bedding — were long ago repurposed into storage rooms for who knows what.

They cling to places like the Ohio Street entrance to East High School, the back of a former State University at Brockport building on Bragdon Place downtown, and the brick façade of Turcott’s Taproom on Monroe Avenue. One sign on the side the Salvation Army building on Liberty Pole Way still notes the capacity — 590 souls.

There is no telling precisely how many public fallout shelters existed in Monroe County. A county spokesperson acknowledged that the county stopped maintaining public shelters after what was known as the federal Office of Civil Defense was dissolved in the 1970s, and that a list of shelter locations has been lost to time.

Archives of news articles and Civil Defense newsletters that were issued quarterly offer the best estimates of the number of shelters. By those accounts, there were anywhere from 400 to 600.

A Civil Defense newsletter from January 1964 read that there were 390 “fully-stocked shelters” in the county that could sustain 192,130 people for two weeks. Ten years later, the county’s Civil Defense shelter officer told the Democrat and Chronicle there were 584 shelters with enough room for 376,534 people.

“And you can rest assured that if the bomb was dropped tomorrow, they’d be ready,” the newspaper reported.

Tomorrow came and went. Two years later, the county Civil Defense agency determined that most of the food inside the shelters was rancid, a fact it reportedly learned after “derelicts had gotten into shelters and became sick from eating the food.” By 1978, the office had been disbanded and the shelters were cleared out in a massive public undertaking.

The fallout shelter initiative in Rochester hit its stride after Gov. Nelson Rockefeller — a zealous proponent of shelters who built his own $3.5 million bunker in Albany — launched a state shelter program in 1960.

Rochester, it was reported often and urgently during the era, was a target due to its technology sector led by Eastman Kodak Co. and Xerox.

The back cover of a Civil Defense manual on do-it-yourself home fallout shelters issued to county residents reinforced the message. “ROCHESTER CAN BE BOMBED!” screamed the headline over a cartoon image of a shadowy bomber plane spanning the globe 3,719 miles from Siberia to Rochester. “Estimated Time of Arrival: ???”

“It was a really scary time and I remember being afraid of the Russians,” said Kate McBride, 68, who recalled building a shelter in the basement of her childhood home on Nunda Boulevard with her father, Jim Borden, in the early 1960s.

She described her father as a Kodak engineer and a World War II veteran who was stationed in occupied Japan and witnessed firsthand the devastation of the atomic bomb.

“I can remember putting the cement between the cinder blocks and helping him build it,” she said. “He took it on as a project and he wanted to protect his family.

“You have to put this in historical context,” she went on. “You think about it now and you think how is that really going to protect anybody? But at the time, I think people took it seriously because the government really took it seriously.”

As Cold War tensions eased, her family’s fallout shelter, which she recalled as being 8 feet-by-8-feet and outfitted with bunk beds and shelves stocked with food and other supplies, became a place for her and her friends to play and sleep.

In addition to spending millions on carving out space for public shelters, the state fallout shelter program offered property tax incentives to homeowners who prepared for a Soviet attack.

There are still nine houses on the city tax roll that receive a tax abatement of between $150 and $200 for having a fallout shelter. One of them is McBride’s childhood home.

Another is around the corner on Hartsen Street that has belonged to Alison and Jovan Livada since December 2019.

“When we toured the house, the realtor was like, ‘I think there may be a bunker in the backyard,’ and we were like, ‘No way! What?’” she said.

The shelter had been filled at some point before the Livadas bought their home and, as far as they can tell, its remaining underground cavities are today a refuge for groundhogs and squirrels. The only evidence that something is, or once was, underneath their backyard lawn is a square brick fire pit that juts from the grass like a chimney.

“It’s always been a joke to just say to friends, ‘You know, when World War III happens, you can help us dig it out, grab your shovel and come on over,’” Livada said with a laugh as she inspected the ground. “We don’t know what’s underneath here, but we’re ready to go.”

David Andreatta is CITY's editor. He can be reached at [email protected].