[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

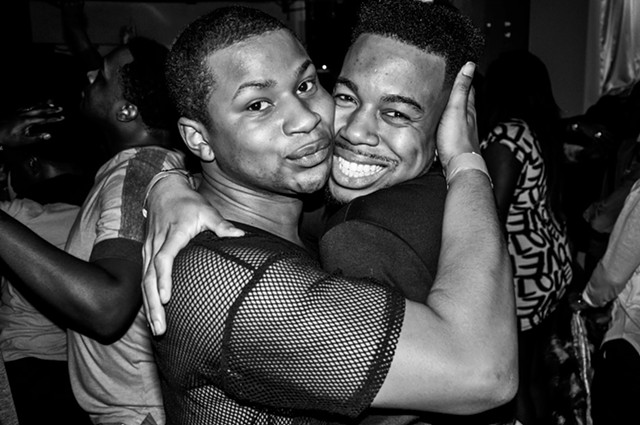

This year marked the third official (and fourth unofficial) year of Rochester Black Pride, a five-day festival that included workshops, youth events, concerts, parties, and a cookout. It grew from the need for spaces and events that center on the culture and safety of queer and trans people of color.

The festival's organizers and some of the attendees say that while LGBTQ people have generally become more visible, accepted, and safe, those gains have mostly been for white, cisgender parts of that community. Queer and trans POC remain the most marginalized, are often targeted for violence, and remain unheard. Trans women — and trans women of color in particular — face higher rates of hate-motivated violence. There are 16 known murders of trans people in the US in 2018.

Rochester Black Pride was founded by artist, filmmaker, and community organizer Adrian Elim, but they don't take full credit for the idea. There are Black Pride festivals in other cities, Elim points out: "DC, New York, Philly, Fayetteville, Chicago — like every major city and then some, there's a Black Pride," they say. "It was just new to Rochester — but not really because the MOCHA Center has always had a MOCHA Weekend that was like an alternative Pride celebration for people of color."

Elim says that there have also always been separate parties that people of color have hosted because to many queer and trans black and brown folks, Pride has always felt overwhelmingly white. "The LGBTQ spaces here are also just really white," Elim says. "They're white-run. They're white-focused."

For people of color, Elim says, there is no separation between cultural, racial identity and sexual orientation and gender identity.

"For us it's still the same issues from 40, 50 years ago, and it's just like, white people don't have that same thing," they say. "I may not be judged for what I'm wearing, but I might still be judged by someone following me around a store, or kicking me out because they assume I can't pay for anything. Or I'm just black in a space, and there's a whole bunch of shit that comes with that."

Hundreds of people attended Black Pride in 2017, in no small part because it hosted Big Freedia for its Summer Nights concert series — that show alone drew up to five hundred folks, Elim estimates.

The festival includes an opening reception with food and performances, a Cocktails & Conversations happy hour, and youth activities and events. Each year there's a cookout on the festival's final day, Sunday. And it's a genuine community feat and fête: "It's free, everybody helps out, everybody brings stuff, people help cook," Elim says.

Another annual feature is Vogue Rochester, a party that is an ode to the Ballroom Scene and includes a competition with categories and prizes. And then there's the festival, which takes place at Edgerton Park.

Elim, in 2015, was organizing with Building Leadership and Community Knowledge (B.L.A.C.K.) and helping plan Black Lives Matter actions, and their feelings about Pride and racial politics converged. "I don't agree with the idea of this whole, 'let me fight to join your table,' just so we can have maybe one or two events that are kinda, sorta inclusive or kinda, sorta representative of our community," Elim says. "And I said, 'Our community is a lot more diverse than that, so I'm just gonna build my own.'"

Elim decided to host a series of black-centered parties and a cookout at the beach during Rochester Pride weekend in 2015. "From there I was just like, well, this could actually be a thing," they say.

The following year Elim put out a call out to have an open planning and collaboration session. Elim started with the question: What would it look like for people to take charge and lead their own Pride? "I don't think I should be planning events for lesbian-identified individuals, or certain groups of trans-identified individuals, because those aren't my identities that I claim," Elim says. "So I thought, 'Why don't I just raise money for them to do their own thing?'"

So Elim and a small group of collaborators raised money and in 2016 they threw the first official Rochester Black Pride. The planning sessions are open to any black or brown people who want to join, Elim says. "It's a lot harder, it takes longer, but it's a lot more rewarding to have a more robust and representative Pride that people do feel they have a part of, that everyone can feel kind of an ownership of, because folks helped put it together."

Tamara Leigh, a professional development specialist for the City of Rochester, entrepreneur, and radio host, joined the team of Black Pride organizers in 2016. She specifically handles a lot of the writing, PR, and media management, and co-coordinates Black Pride's annual Black Queer Prom. This year Leigh helped put together the Studs & Stilettos Party, a woman-focused Cocktails & Conversations event that served as both a social happy hour and a space for important discussions about issues the community faces.

Leigh echoes many of Elim's criticisms about the LGBTQ community and Rochester Pride. "Although I never quite understand it, within our already marginalized gay community racism still very much exists," Leigh says. While she has never been turned away from a mainstream Pride event, "it is certainly not an environment created to reflect or be inviting to the queer community of color," she adds.

Zora Gussow, a white, non-binary queer activist who co-founded Trigger Warning Queer and Trans Gun Club, has attended parts of both festivals. Gussow is generally skeptical of mainstream Pride events because they tend to be rather corporate, focus mostly on white, cis gay men, and are more focused on alcohol than Gussow is comfortable with.

"Having a Black Pride is one way to create spaces that push against those dynamics and are comfortable and welcoming to a vital part of the LGBTQ community that often gets marginalized," Gussow says.

Gussow adds that they don't really feel comfortable in white LGBTQ spaces in general, "because they tend to be more rigid and less accepting of LGBTQ people who don't fit in the boxes well," such as non-binary and gender queer people, trans people who don't wish to or aren't able to medically transition, and anyone non-white and middle-class.

While Gussow says they recognize that Pride has an important role in the LGBTQ community, they are frustrated by the fact that it could be more inclusive and more political. "I would love to see a Pride Parade where politicians are only allowed to march if they've made concrete campaign promises related to supporting the LGBTQ community, and are held to those promises once Pride is over," they say.

The Rochester Pride executive team says it is aware of these concerns and criticisms, and that it's working to make the festival more inclusive and intersectional.

After listening to community feedback after the 2017 festival, Roc Pride invited more people to join the 2018 executive team, to better reflect the diversity of the LGBTQ community, says Jeff Myers, the interim executive director of Out Alliance. The additions included ASL interpreter, Civil Rights activist, and spoken word poet Christopher Coles; Jazzelle Bonilla, who is an entrepreneur and serves on the Rochester Victory Alliance's Community Education & Outreach team; and Barb Turner, a founding staff member of MOCHA and Prevention Educator for Hep C and HIV at Anthony Jordan Health Centers.

These efforts manifested last July in a week of Pride events branded as "Stand Out Loud and Live in Color." Myers says that in addition to working toward inclusiveness — particularly through more diversity in the selected performers — the Pride team was focused on making the festival more accessible for people with mobility issues and made sure that there were ASL interpreters for all events.

Planning for Roc Pride 2019 is underway, Myers says, and the focus going forward will be to continue efforts to make sure that everyone feels safe and welcomed in every space.

"Roc Pride continues to grow," he says, "and we are looking at ways to expand on accessibility and will continue to mix local talent into our performances."

This will include working with community partners to bring more diversity in the events into the Roc Pride schedule, Myers says. "Our goal is to have a week-long celebration of Pride and being our authentic selves, while educating and advocating on issues that impact our community."

But, Myers says, the Out Alliance understands the necessity of Black Pride and supports it, and that members of Rochester Pride's executive team are affiliated with Black Pride as well. Efforts to make mainstream Pride more inclusive doesn't mean Black Pride will become unnecessary.

Tamara Leigh says that it's important and fair "to give our community within our community within a community the same open, safe, accepting and reflective space that all other gay people demand. One wouldn't question why we have a Rochester Pride festival instead of everyone just going to the Lilac Festival. Creating a safe, inviting space where queer people of color can be celebrated opposed to simply tolerated shouldn't require an explanation."

Because the Black Pride Festival is held at Edgerton Park, there are a lot of kids hanging out on the periphery of the festival; some end up attending. This unexpected aspect has the potential to normalize marginalized people in the minds of younger community members, especially since the festival recurs in the same spot, Elim says. "It's really dope, because at first they were like 'wait, what's going on?' Like last year they were like, 'cool, this is just another thing.' And it's like, building better, more holistic people in the world, which makes it safer for everyone."

Elim and Black Pride regularly partner with The MOCHA Center, which each year hosts a youth day party; this year that gathering was thrown at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Park during Black Pride.

Black Pride organizers say they want to shift a lot of their efforts and focus toward engaging and supporting marginalized youth.

"There are so many black and brown youth that, on top of being black and brown, they have all those other layers on top of it that they have to face," Elim says. "Whether it's family, church — this, that, or the third — it's the same stories that folks my age went through, folks right under us, and now 12-, 13-year-olds coming up. It's the same story still."

Elim says that it's obviously a goal to grow the festival to a point where it can both attract and afford flashier and flashier celebs, which will in turn garner more fiscal support for the festival to run. But they say their primary concern is making this event a beacon for young queer POC and trans folk who need supportive community immediately.

"We talk about moving forward, we talk about what that looks like, what's the agenda for moving folks forward," Elim says. "And again there's that divide in terms of like: I don't give a fuck about marriage. I need to make sure my folks have a place to sleep at night. I need to make sure they're not getting kicked out of their homes. I need to make sure that their mental health is stable. I need to make sure that they have jobs. I need to make sure that they're not in physical danger every day."

A big issue to the Pride divide, Elim says, is that many people of color and trans people feel that they and their specific, ongoing concerns were left behind when white and cisgender lesbian, gay, and bisexual people gained more acceptance, safety, and visibility in wider culture.

And that's a particular slap in the face, "considering where Pride started from: with Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, Miss Major, and other black and brown trans women resisting the police," Elim says. "Now it's just like, party party party party — and then white people jumping in front of it, and whatever they say goes ... like, how did we get here?"

A deliberate difference between Rochester Pride and Rochester Black Pride is a lack of police presence. "It's really simple," Elim says, "I went to the city and I said, 'I refuse to have police at Pride.' At all."

Aside from the fraught history between the police and LGBTQ community members, there's an enduring, fever-pitch fear of the police by people of color, immigrants, and others.

"People assume that this issue between the larger LGBT community and the police is in the past — a 70's, 60's thing," Elim says. "Where, with black and brown bodies — regardless of how they identify — that relationship with the police will always be tumultuous, will always be violent. Coming from police. That's because of the neighborhoods we grow up in, walking down the street, people just sitting around doing nothing — someone feeling the need to just like, 'Oh, let me call the police,' because we're taking up space."

Elim says that City Hall knows where they stand on the matter: "It's so simple: I am not paying the police, I will not do it. I don't care if it's $20, I am not paying them."

Permit wise, refusing to have the police involved means Black Pride can't have a parade. But as long as it has its own personal security for the festival, organizers don't have to hire the police.

"But half of the security is queer anyway," Elim says. "We use a security company that I met going to other queer parties. And in general they're cool, they're chill. Honestly they spend most of the day just walking around and doing nothing. And by that I mean, it's probably one of their favorite events because nothing happens."

Jeff Myers says he wants to be clear that Rochester Pride paying the police is a requirement of the City of Rochester. "This is not a choice we make," he says. "RPD is paid for crowd control during the parade as well as the city streets surrounding the festival site. The Out Alliance pays for private security to be inside the festival grounds to ensure that folks are safe. We have always had private security at the picnic and festival."

The second you put "black" in front of anything, there are all these problems and pushback, Elim says. "The festival and parties are meant to be safe spaces for the community, for black and brown queer and trans folks," they say. "But allies are definitely welcome to come. It's just that we have a certain safe space code. If you don't wanna follow that, you don't have to be here. Very simple. The safety of my folks, and the safety or the mental health of my people for this Pride runs paramount to anything."

And plenty of white people attend the festival each year, Elim says. "But they can respect the space, and the necessity of that space. The black part is where the cultural focus will be."

One of the elements of organizing Black Pride that Elim says is particularly gratifying is that the festival is intergenerational, and that this helps build a stronger community.

"Our people are dying, but they aren't just dying, our community loses track of them, they go somewhere else," Elim says. "We can't keep doing that. There is a wealth and a power and a wisdom in having community, among people of all spectrums and all ages."

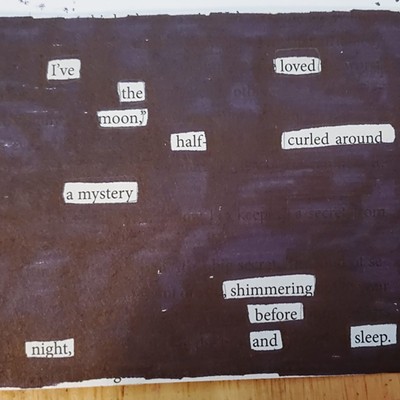

And it's crucial for young queer and trans POC to see themselves represented in the narrative of growing old with somebody, Elim says. "That's big. But in the planning you don't realize how much it's gonna have an impact on others and yourself."

Elim says they're grateful for the community that has worked over the years to make Black Pride as safe and fun as possible. And every year, with new support and new collaborators, it's getting better and even more inclusive.

"With all that we as black queer and trans people face on a daily basis, we, much like those who came before us, continue to make space for ourselves to be great," Elim says. "With all the things stacked against us, we are still triumphant — and you better believe we do it with style, uniqueness, and without apology."

Speaking of...

Latest in News

More by Rebecca Rafferty

-

Beyond folklore

Apr 4, 2024 -

Partnership perks: Public Provisions @ Flour City Bread

Feb 24, 2024 -

Raison d’Art

Feb 19, 2024 - More »