This is Malik Evans: Everything you ever wanted to know about Rochester's next mayor

By Gino Fanelli @GinoFanelli[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Malik Evans was uncomfortable, uncharacteristically, visibly uncomfortable.

Sitting at the head of a hardwood conference table in his campaign headquarters on the 10th-floor penthouse of an East Avenue office building in the heart of downtown, Evans was preparing to do something he takes pains to avoid: talk about himself.

Rochester’s presumptive mayor-elect is partial to talking about things like policy and vision and what he calls “building bridges” through his “compact with the community.” Fifteen minutes prior to our interview for a profile on him, his spokesperson called to ask if I could avoid asking him too much about his personal life and, instead, focus on issues.

The answer was no.

The issues have been well documented. The city is reeling from the economic fallout of the pandemic and the ongoing social and racial justice reckonings. Violent crime is the highest it has been in decades and has spilled into the public schools, which have been in shambles for as long as anyone can remember. Trust in city government and its institutions has eroded.

What people want to know is who this 41-year-old man who thinks he can fix the problems is. Despite Evans spending nearly half his life in the public eye, his name preceded by a handful of elected-office titles he has held, remarkably little has been chronicled about the man behind School Commissioner-School Board President-City Councilmember-presumptive Mayor-elect Evans.

“Oh, God,” he said, burying his forehead into a palm in resignation upon being reminded that our interview was for a personal profile.

In a political ecosystem fueled more and more by populism and big personalities, Evans is an outlier. He is decidedly reserved. He doesn’t take digs at his opponents. He doesn’t boast about his political achievements, but that may be because in a city with Rochester’s problems there aren’t too many that stand out.

He isn’t flashy, either. The checkerboard suit jacket he wore that day hung, like much of his wardrobe, a bit too loose on his thin frame. Some might call him boring, better suited to sticking to his day job as a banker at ESL Federal Credit Union than running a city.

But the understated, everyman persona Evans has cultivated has worked for him. For those close to him, his successful mayoral run was the culmination of a near lifelong journey of a calculating politician who is known in every corner of the city.

“He’s somebody who can talk in churches in the northeast or northwest quadrant, and then walk around the Park Avenue neighborhood and talk to people there and recognize that every single neighborhood matters,” said Gerald Gamm, a political science professor who taught Evans at the University of Rochester and now considers him a friend.

“The metaphor he had at the start of that (mayoral) campaign, ‘Vote for me and I’ll build bridges,’ I thought it was really hokey at first, and I actually made fun of it, ‘So Malik, you’re going to build bridges for us?’” Gamm said. “But I actually came to appreciate it was genuine, it was deep, and it was sincere. But that’s who Malik is.”

HIS FATHER’S SON

Evans grew up the fourth of six children in a blue two-story home on Hamilton Street in the South Wedge. To hear him tell it, he was a typical child of the late 1980s and early 1990s who played basketball and video games — his favorite was NES Tecmo Bowl — like every other kid in the neighborhood.

But the Evans house wasn’t like every other house in the neighborhood.

For one thing, the house at 219 Hamilton St. doubled as a church of sorts, a church of something called “Doology,” a faith Evans’s father had created as a teenager on the premise that doing something to improve the problems in one’s community was more valuable than sitting around and complaining about them.

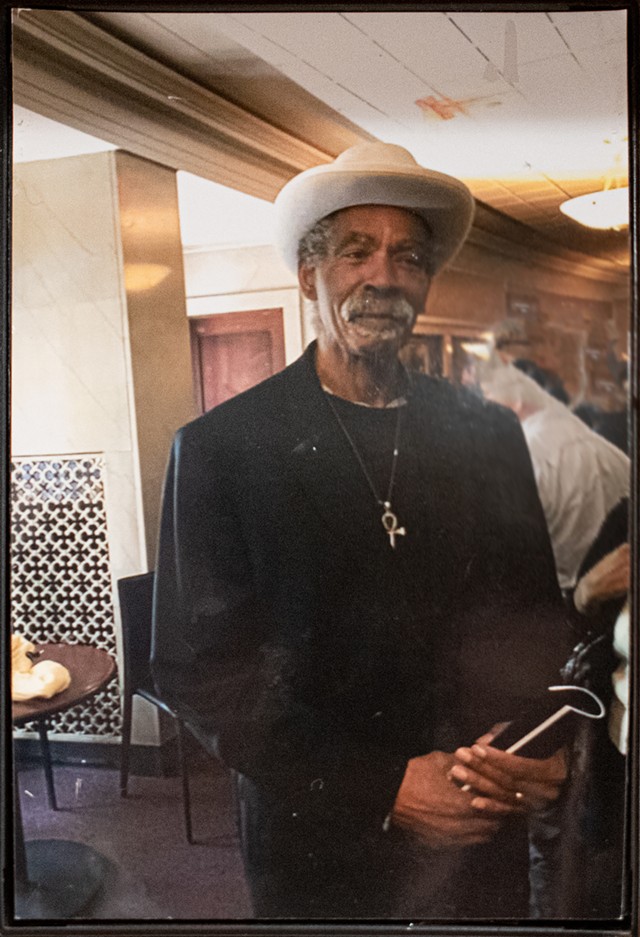

The Rev. Lawrance Lee Evans Sr., who went by the title of “minister,” founded the First Community Interfaith Institute in 1970, a decade before Malik was born, and ran services out of the family home on Hamilton Street. The house was a revolving door of prayer, tutoring, lectures, and activism.

On different days of the week, one could pop into the Evans home for a lecture on “King and his contemporaries,” or a sermon on solutions to racism, sexism, and classism. There were studies on Malcolm X and African-American history. The church’s activities were a near weekly fixture in the classified pages and community calendars of local newspapers for years.

“This house would just be full of young people all learning about their history, their culture, and exactly how important education was,” said Nancy Johns Price, a longtime friend of the Evans family and a former administrator for the city’s Southeast Quadrant Neighborhood Service Center who is now on Evans’s mayoral transition team. “That’s what (Minister Evans’s) belief was.”

The year Evans was born, his father reportedly lectured Internal Revenue Service workers on Black history and organized a rally at the former Americana-Rochester Hotel over alleged racial discrimination. A year later, he attempted to organize a Black community-focused security force following the racially-charged stabbing death of a man named Windell Barnes as he waited for a city bus downtown. For a time, he ran a program for high school dropouts through the Rochester City School District and, later, retired from Rochester General Hospital as a case manager for homeless people.

“My father was the most righteous man I’ve ever met,” Evans said. “He also had a lot more patience than I did. I’m very impatient, not in a bad way, but I think we can move things along faster, whether in the way we organized the campaign or my life.”

Minister Evans ran unsuccessfully for office on at least two occasions before Evans was born.

He challenged an incumbent assemblyman, Gary Proud, in the 1978 Democratic primary, after a failed run for the city school board the previous year. When asked to criticize his opponent in a Democrat and Chronicle interview that year, he declined, saying only that he’d like to see “more positive leadership.”

His son would display the same tact 43 years later in his run for mayor, when Evans refused to make hay of the turmoil in Mayor Lovely Warren’s political and personal life that would, in part, lead to her defeat by Evans in the Democratic primary and eventual resignation from office.

Under the terms of a plea deal to satisfy charges in two criminal cases against her, Warren is scheduled to step down on Dec. 1. She will be replaced by her deputy, James Smith, until Evans is sworn in on Jan. 1.

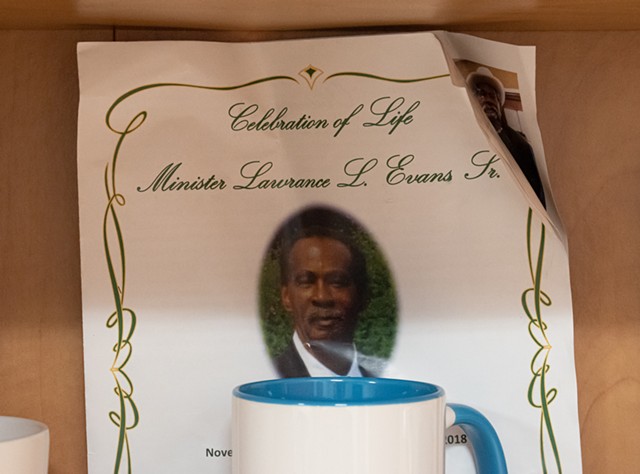

If Minister Evans infected his son with the political bug, he and his wife, Gwendolyn, also instilled in their son the sense that life is short. Gwendolyn, who was also known as MaAkilah, died in 2012 at the age of 65. Lawrance died six years later, also of cancer. He was 72.

“Not everyone has a Gwen and Lawrance Evans,” Evans said. “That helped me, that’s the differentiator. I’d be lying if I said I would be where I am without my parents. They were my first teachers.”

If Evans was to accomplish anything, it had to be now. Not tomorrow. Not next year. Now. Evans recalled the death of his parents as a tremendous loss and credited them for shaping the man he has become.

“Him and my mother had a formula and it worked,” Evans said. “I don’t know what the heck it was, but it worked. He was just brilliant as it related to empowering his kids. Nobody believed in me more than my mother and father.”

A YOUTHFUL LEADER

In 2003, at the age of 23, Evans accomplished what his father couldn’t when he was elected to the Rochester Board of Education, becoming the youngest commissioner in history.

By that time, however, he was well into his public advocacy work.

In 1996, at the age of 16, Evans helped found the City/County Youth Council, a group of what Johns Price called “brilliant” young people who sought to give a voice to their peers. She recalled how Evans, who would head the group into his college years, spurred on members.

“Malik made sure that we got our rear ends into gear,” Johns Price said.

That program became Youth Voice, One Vision in 2001 under Mayor Bill Johnson, and still operates today.

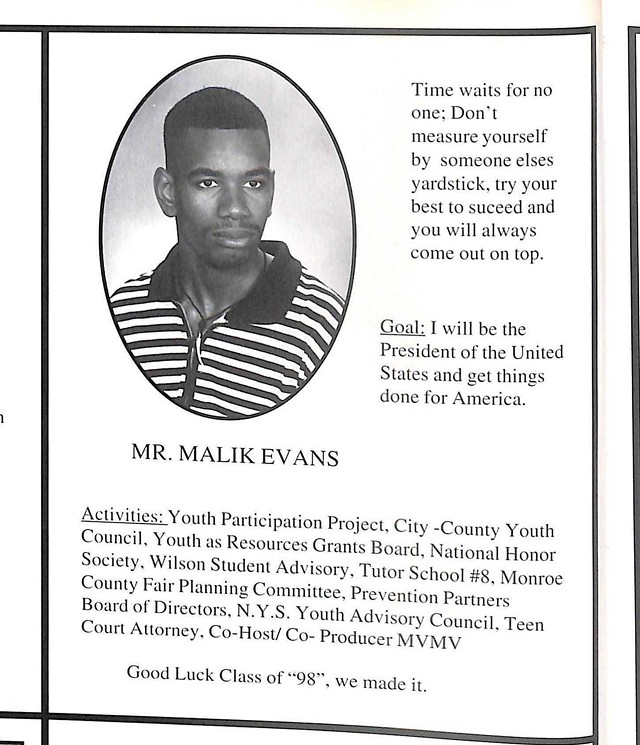

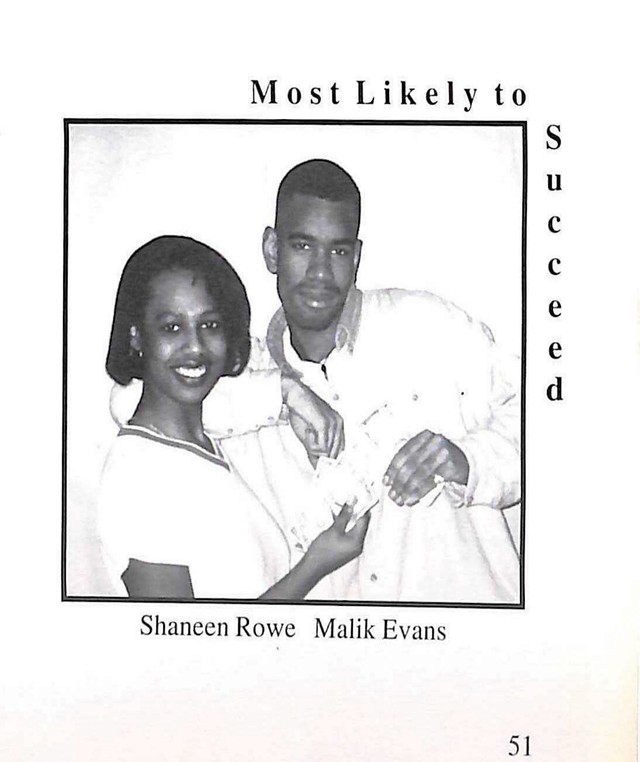

Evans’ years at Joseph C. Wilson Magnet High School cemented him as a young person set on leading. He was nominated “Most Likely to Succeed” and became the first student to be honored two years in a row with the Rochester Teachers Association’s “King Spirit Award,” granted to students demonstrating the values of Martin Luther King Jr.

“I have long range plans,” Evans told the Democrat and Chronicle in an article detailing his win. “I want to be a major driving force in politics, especially in this community.”

On the mayoral campaign trail, Evans lamented the violence among young people plaguing the city and pushed the idea that getting kids to pick up something — work, community service, sports, anything — would leave them less time to pick up a gun.

The concept was based on his own experience. In his high school days, he volunteered and worked. As if Evans couldn’t get any more wholesome, his first job was at 15 selling his mother’s cookies outside their Hamilton Street home. He later found work with the city’s recreation department.

He and others who knew him in those years likened his school locker to a phone booth for Superman. There, he would swap out his street clothes and sneakers — he prides himself as being the first kid at Wilson Magnet to have a pair of Nike Air Worm Ndestrukts, Dennis Rodman’s inaugural swoosh-branded kicks — for a suit that would become his more familiar attire.

He wore that suit often, he recalled, including constantly to one of his most memorable endeavors — Teen Court.

Evans was 17 when then-City Court Judge Frank Geraci Jr. began a pilot program consisting of mock trials for youth offenders already found guilty on minor charges in real court. Fellow teens would serve as prosecutors, defense attorneys, and a jury.

“I remember him like it was yesterday,” Geraci, now a federal judge, said of Evans with a chuckle. “Malik bought into the whole thing. He had great ideas, he was very creative, and he was really caring with these teens.”

Geraci saw a spark in Evans at a young age, to the point where watching him step into the shoes as the next mayor comes as no surprise.

“I saw that commitment right at the beginning, I saw his commitment to the community, he was smart,” Geraci said. “I always expected him to go into some kind of community service.”

Mention Teen Court to Evans and his eyes light up. He recalled getting involved as an “attorney” to fine-tune his public speaking skills. His friends, he said, urged him to go to law school.

“I said, ‘Oh no, I’m not doing that,’” he said.

FROM UR TO THE SCHOOL BOARD

That Evans harbored political ambitions was no secret to anyone who knew him. The question was how they would materialize.

He entered the University of Rochester in 1999 with visions of being a political journalist, something like the late Ed Bradley of “60 Minutes.”

“I thought I’d be a reporter in D.C., and then maybe go into politics later on,” Evans said.

He scuttled those plans after a veteran local photojournalist, Carl Shuba, who died in 2017, made him think twice about a career that is around-the-clock and low paying.

“Carl told me, ‘You like doing community stuff, do you want to have to work on Thanksgiving and all of these other times?’” Evans recalled. “I said, “No, I don’t want to do that.’”

Evans set course for a career in finance and politics, becoming the treasurer of the university’s Student Activities Appropriations Committee, an organization that held the purse strings for various campus groups. He led Kwanzaa celebrations, tutored students at Roberto Clemente School No. 8, and joined Mayor Bill

Johnson’s taskforce on city’s nightclubs, studying the options and code enforcement for Black clubs.

He dabbled in what he called “rabble-rousing,” too. Evans was part of a 200-student sit-in outside then-University President Thomas Jackson’s office in 1999 calling for the preservation of the Frederick Douglass Institute for African and African-American Studies.

Gamm, his former political science professor, recalled Evans as a student eager to challenge him.

“Malik, even as a college student, was really, really good at listening to other students, taking other students seriously, and not talking over other people,” Gamm said. “When I was standing there looking to the class and asking, ‘What do you think of the reading, what questions do you have?’ Malik would routinely speak up.”

Upon graduating, Evans wasted no time earning his political bona fides in the real world. Just weeks out of college, he announced his candidacy for the school board.

The campaign was a family affair. His older brother, Lawrance Lee Evans, Jr., an economist, sold signed copies of his first book, an academic text on the stock market boom and bust called “Why the Bubble Burst,” and gave the proceeds to the campaign.

Evans won the seat with the second-highest number of votes of any candidate, pulling in about 13 percent of the ballot. Five years later, he would also become the board’s youngest president, a position he held from 2008 to 2013. He resigned in 2017 to pursue an at-large seat on City Council.

Through his time on the school board and City Council, which were both paid positions and considered part-time work, Evans kept his job at ESL Federal Credit Union. He has said he will step down from the bank before assuming the mayoralty.

The RCSD had already been limping from crisis to crisis before Evans joined the board, and there were few outward signs of improvement during his tenure. Tumult was the order of the day, as the district cycled through superintendents, grappled with budget deficits, fended off talk of mayoral control of the school system, and student achievement stagnated.

Six years into his tenure on the board, the state comptroller released an audit that found the school board had failed to protect the district’s financial interests from waste and abuse by past superintendents and their top aides, took little or no action to control tens of thousands of dollars in undocumented bonuses, and awarded millions of dollars in no-bid contracts.

Evans, who was the new president, at the time dismissed the findings as “old news” and said the board had since corrected its deficiencies, including ousting some top officials.

“It was very tumultuous, it was very volatile, there was a lot of interpersonal squabbling,” said Shirley Thompson, who was a school commissioner from 2000 to 2007.

Her time on the board was so toxic, she said, that she has tried to leave those days as a distant memory. But she recalled Evans as a thoughtful commissioner who shared her motivations of community service.

“Malik was a very solid board member,” Thompson said. “One of the things I liked about Malik was he was very approachable, and he was very present.”

When Evans joined the board, the district had an on-time graduation rate of about 55 percent. When he left in 2017, the rate was at 57 percent.

Today, he is ambivalent about his time on the school board. There were some good things — he points to Wilson Magnet being ranked 27th best high school in the nation by Newsweek in 2005 as a high point — but acknowledged that the issues he confronted have snowballed.

“The challenges the district faced were 50 years in the making even when I got there,” Evans said. “You had declining enrollment, you had high levels of poverty, and you had some folks that believed that, ‘Oh no, these kids can’t do it.’”

He added: “I always say that I wish there was more that could have been done, but I gave a lot of my formative years to the school board.”

A MAYOR IN THE MAKING

When Evans trounced Warren in the Democratic primary in June, effectively clinching the mayor’s job, his victory surprised many people.

After all, he was facing a two-term incumbent and a politician regarded by many to be coated in Teflon. At the outset of his campaign, political observers, including his friend, Gamm, publicly regarded his pursuit as an uphill battle.

But people closest to Evans were not surprised.

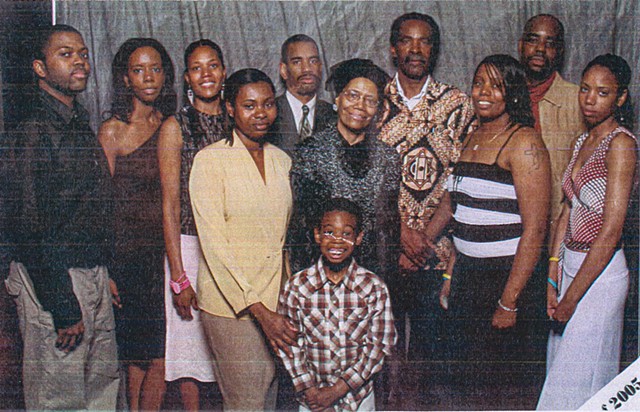

“Our father and mother wouldn’t be surprised. He said in the first grade that he wanted to be the president of the United States,” said his younger sister, LaShara Evans. “He laughs now and says, ‘I don’t want to be the president.’ But we knew he would always go into politics. And business, we knew he would go into banking as well.”

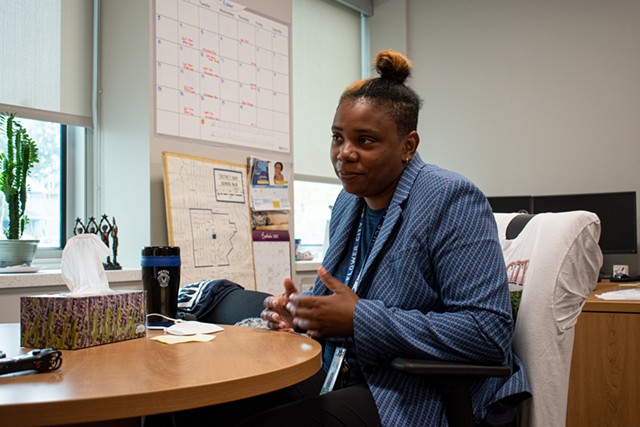

LaShara Evans is the principal of Flower City School No. 54. Her office has a floor-to-ceiling bookshelf adorned with family photos and mementos that reveal the closeness of the Evans family. She said she and Evans talk by phone twice a week.

Like her brother, she credited their parents for what success she and her siblings have found.

Lawrance Lee Evans Jr. is now the managing director of financial markets and community investment for the United States Government Accountability Office. Akilah Evans, the youngest sister, is a medical doctor in Syracuse.

But the Evans household isn’t all work and no play. The presumptive mayor-elect lives in the Cobbs Hill neighborhood with his wife, Shawanda, and their two boys, Cameron and Carter, with whom he said he finds time to play the now-vintage video games of his youth as well as more modern games in NBA 2K or Madden.

“That’s probably the biggest escape I have, my kids bragging and talking junk,” Evans said.

He said he’s grateful his boys enjoy football like him. But like other long-suffering Buffalo Bills parents, he’s shouldering the ultimate betrayal: his sons root for the Philadelphia Eagles and the Baltimore Ravens.

“They’re so disrespectful,” Evans said, jokingly. “But I’ll tell you, if the Bills win the Super Bowl, we’re shutting down the city.”

Evans met Shawanda during his early years in banking at a career day she had helped organize in the basement of Aenon Baptist Church. They would get married in the same church years later.

“She felt sorry for me,” Evans said. “I was doing a career day, she was running the career day, and she wouldn’t give me the time of day. And then someone said, ‘You know, I think he’s a nice guy.’”

On the campaign trail, Evans repeatedly promised a transparent and inclusive administration without ego. What he wants, he said, is to inspire not only his city, but his children.

“The biggest difference I want to make is the difference in the life of my kids,” Evans said. “I want them to know that their father did everything he could do to not only provide for them and make sure they were strong men and could provide for their family, but I also didn’t forget about the larger community.”

Evans said his job as mayor would be to pull together the city to tackle its challenges. After years in politics and public service, with more ahead, Evans waxes philosophical about his view of government.

“I wanted to make sure that the space I take up on this little planet, which we all take up, when you think about the planet, not to sound esoteric, but the planet is billions of years old,” he said. “All of us are but a speck in the span of the billions of years the Earth has been here. So what difference will you make?

“On my tombstone,” Evans went on, “I want it to say, ‘You know what? He tried.’”

CORRECTION: The original version of this story misidentified the church where Malik and Shawanda Evans met. The story has been updated with the accurate information.

Gino Fanelli is a CITY staff writer. He can be reached at (585) 775-9692 or [email protected].

Sitting at the head of a hardwood conference table in his campaign headquarters on the 10th-floor penthouse of an East Avenue office building in the heart of downtown, Evans was preparing to do something he takes pains to avoid: talk about himself.

Rochester’s presumptive mayor-elect is partial to talking about things like policy and vision and what he calls “building bridges” through his “compact with the community.” Fifteen minutes prior to our interview for a profile on him, his spokesperson called to ask if I could avoid asking him too much about his personal life and, instead, focus on issues.

The answer was no.

The issues have been well documented. The city is reeling from the economic fallout of the pandemic and the ongoing social and racial justice reckonings. Violent crime is the highest it has been in decades and has spilled into the public schools, which have been in shambles for as long as anyone can remember. Trust in city government and its institutions has eroded.

What people want to know is who this 41-year-old man who thinks he can fix the problems is. Despite Evans spending nearly half his life in the public eye, his name preceded by a handful of elected-office titles he has held, remarkably little has been chronicled about the man behind School Commissioner-School Board President-City Councilmember-presumptive Mayor-elect Evans.

“Oh, God,” he said, burying his forehead into a palm in resignation upon being reminded that our interview was for a personal profile.

In a political ecosystem fueled more and more by populism and big personalities, Evans is an outlier. He is decidedly reserved. He doesn’t take digs at his opponents. He doesn’t boast about his political achievements, but that may be because in a city with Rochester’s problems there aren’t too many that stand out.

He isn’t flashy, either. The checkerboard suit jacket he wore that day hung, like much of his wardrobe, a bit too loose on his thin frame. Some might call him boring, better suited to sticking to his day job as a banker at ESL Federal Credit Union than running a city.

But the understated, everyman persona Evans has cultivated has worked for him. For those close to him, his successful mayoral run was the culmination of a near lifelong journey of a calculating politician who is known in every corner of the city.

“He’s somebody who can talk in churches in the northeast or northwest quadrant, and then walk around the Park Avenue neighborhood and talk to people there and recognize that every single neighborhood matters,” said Gerald Gamm, a political science professor who taught Evans at the University of Rochester and now considers him a friend.

“The metaphor he had at the start of that (mayoral) campaign, ‘Vote for me and I’ll build bridges,’ I thought it was really hokey at first, and I actually made fun of it, ‘So Malik, you’re going to build bridges for us?’” Gamm said. “But I actually came to appreciate it was genuine, it was deep, and it was sincere. But that’s who Malik is.”

HIS FATHER’S SON

Evans grew up the fourth of six children in a blue two-story home on Hamilton Street in the South Wedge. To hear him tell it, he was a typical child of the late 1980s and early 1990s who played basketball and video games — his favorite was NES Tecmo Bowl — like every other kid in the neighborhood.

But the Evans house wasn’t like every other house in the neighborhood.

For one thing, the house at 219 Hamilton St. doubled as a church of sorts, a church of something called “Doology,” a faith Evans’s father had created as a teenager on the premise that doing something to improve the problems in one’s community was more valuable than sitting around and complaining about them.

The Rev. Lawrance Lee Evans Sr., who went by the title of “minister,” founded the First Community Interfaith Institute in 1970, a decade before Malik was born, and ran services out of the family home on Hamilton Street. The house was a revolving door of prayer, tutoring, lectures, and activism.

On different days of the week, one could pop into the Evans home for a lecture on “King and his contemporaries,” or a sermon on solutions to racism, sexism, and classism. There were studies on Malcolm X and African-American history. The church’s activities were a near weekly fixture in the classified pages and community calendars of local newspapers for years.

“This house would just be full of young people all learning about their history, their culture, and exactly how important education was,” said Nancy Johns Price, a longtime friend of the Evans family and a former administrator for the city’s Southeast Quadrant Neighborhood Service Center who is now on Evans’s mayoral transition team. “That’s what (Minister Evans’s) belief was.”

The year Evans was born, his father reportedly lectured Internal Revenue Service workers on Black history and organized a rally at the former Americana-Rochester Hotel over alleged racial discrimination. A year later, he attempted to organize a Black community-focused security force following the racially-charged stabbing death of a man named Windell Barnes as he waited for a city bus downtown. For a time, he ran a program for high school dropouts through the Rochester City School District and, later, retired from Rochester General Hospital as a case manager for homeless people.

“My father was the most righteous man I’ve ever met,” Evans said. “He also had a lot more patience than I did. I’m very impatient, not in a bad way, but I think we can move things along faster, whether in the way we organized the campaign or my life.”

Minister Evans ran unsuccessfully for office on at least two occasions before Evans was born.

He challenged an incumbent assemblyman, Gary Proud, in the 1978 Democratic primary, after a failed run for the city school board the previous year. When asked to criticize his opponent in a Democrat and Chronicle interview that year, he declined, saying only that he’d like to see “more positive leadership.”

His son would display the same tact 43 years later in his run for mayor, when Evans refused to make hay of the turmoil in Mayor Lovely Warren’s political and personal life that would, in part, lead to her defeat by Evans in the Democratic primary and eventual resignation from office.

Under the terms of a plea deal to satisfy charges in two criminal cases against her, Warren is scheduled to step down on Dec. 1. She will be replaced by her deputy, James Smith, until Evans is sworn in on Jan. 1.

If Minister Evans infected his son with the political bug, he and his wife, Gwendolyn, also instilled in their son the sense that life is short. Gwendolyn, who was also known as MaAkilah, died in 2012 at the age of 65. Lawrance died six years later, also of cancer. He was 72.

“Not everyone has a Gwen and Lawrance Evans,” Evans said. “That helped me, that’s the differentiator. I’d be lying if I said I would be where I am without my parents. They were my first teachers.”

If Evans was to accomplish anything, it had to be now. Not tomorrow. Not next year. Now. Evans recalled the death of his parents as a tremendous loss and credited them for shaping the man he has become.

“Him and my mother had a formula and it worked,” Evans said. “I don’t know what the heck it was, but it worked. He was just brilliant as it related to empowering his kids. Nobody believed in me more than my mother and father.”

A YOUTHFUL LEADER

In 2003, at the age of 23, Evans accomplished what his father couldn’t when he was elected to the Rochester Board of Education, becoming the youngest commissioner in history.

By that time, however, he was well into his public advocacy work.

In 1996, at the age of 16, Evans helped found the City/County Youth Council, a group of what Johns Price called “brilliant” young people who sought to give a voice to their peers. She recalled how Evans, who would head the group into his college years, spurred on members.

“Malik made sure that we got our rear ends into gear,” Johns Price said.

That program became Youth Voice, One Vision in 2001 under Mayor Bill Johnson, and still operates today.

Evans’ years at Joseph C. Wilson Magnet High School cemented him as a young person set on leading. He was nominated “Most Likely to Succeed” and became the first student to be honored two years in a row with the Rochester Teachers Association’s “King Spirit Award,” granted to students demonstrating the values of Martin Luther King Jr.

“I have long range plans,” Evans told the Democrat and Chronicle in an article detailing his win. “I want to be a major driving force in politics, especially in this community.”

On the mayoral campaign trail, Evans lamented the violence among young people plaguing the city and pushed the idea that getting kids to pick up something — work, community service, sports, anything — would leave them less time to pick up a gun.

The concept was based on his own experience. In his high school days, he volunteered and worked. As if Evans couldn’t get any more wholesome, his first job was at 15 selling his mother’s cookies outside their Hamilton Street home. He later found work with the city’s recreation department.

He and others who knew him in those years likened his school locker to a phone booth for Superman. There, he would swap out his street clothes and sneakers — he prides himself as being the first kid at Wilson Magnet to have a pair of Nike Air Worm Ndestrukts, Dennis Rodman’s inaugural swoosh-branded kicks — for a suit that would become his more familiar attire.

He wore that suit often, he recalled, including constantly to one of his most memorable endeavors — Teen Court.

Evans was 17 when then-City Court Judge Frank Geraci Jr. began a pilot program consisting of mock trials for youth offenders already found guilty on minor charges in real court. Fellow teens would serve as prosecutors, defense attorneys, and a jury.

“I remember him like it was yesterday,” Geraci, now a federal judge, said of Evans with a chuckle. “Malik bought into the whole thing. He had great ideas, he was very creative, and he was really caring with these teens.”

Geraci saw a spark in Evans at a young age, to the point where watching him step into the shoes as the next mayor comes as no surprise.

“I saw that commitment right at the beginning, I saw his commitment to the community, he was smart,” Geraci said. “I always expected him to go into some kind of community service.”

Mention Teen Court to Evans and his eyes light up. He recalled getting involved as an “attorney” to fine-tune his public speaking skills. His friends, he said, urged him to go to law school.

“I said, ‘Oh no, I’m not doing that,’” he said.

FROM UR TO THE SCHOOL BOARD

That Evans harbored political ambitions was no secret to anyone who knew him. The question was how they would materialize.

He entered the University of Rochester in 1999 with visions of being a political journalist, something like the late Ed Bradley of “60 Minutes.”

“I thought I’d be a reporter in D.C., and then maybe go into politics later on,” Evans said.

He scuttled those plans after a veteran local photojournalist, Carl Shuba, who died in 2017, made him think twice about a career that is around-the-clock and low paying.

“Carl told me, ‘You like doing community stuff, do you want to have to work on Thanksgiving and all of these other times?’” Evans recalled. “I said, “No, I don’t want to do that.’”

Evans set course for a career in finance and politics, becoming the treasurer of the university’s Student Activities Appropriations Committee, an organization that held the purse strings for various campus groups. He led Kwanzaa celebrations, tutored students at Roberto Clemente School No. 8, and joined Mayor Bill

Johnson’s taskforce on city’s nightclubs, studying the options and code enforcement for Black clubs.

He dabbled in what he called “rabble-rousing,” too. Evans was part of a 200-student sit-in outside then-University President Thomas Jackson’s office in 1999 calling for the preservation of the Frederick Douglass Institute for African and African-American Studies.

Gamm, his former political science professor, recalled Evans as a student eager to challenge him.

“Malik, even as a college student, was really, really good at listening to other students, taking other students seriously, and not talking over other people,” Gamm said. “When I was standing there looking to the class and asking, ‘What do you think of the reading, what questions do you have?’ Malik would routinely speak up.”

Upon graduating, Evans wasted no time earning his political bona fides in the real world. Just weeks out of college, he announced his candidacy for the school board.

The campaign was a family affair. His older brother, Lawrance Lee Evans, Jr., an economist, sold signed copies of his first book, an academic text on the stock market boom and bust called “Why the Bubble Burst,” and gave the proceeds to the campaign.

Evans won the seat with the second-highest number of votes of any candidate, pulling in about 13 percent of the ballot. Five years later, he would also become the board’s youngest president, a position he held from 2008 to 2013. He resigned in 2017 to pursue an at-large seat on City Council.

Through his time on the school board and City Council, which were both paid positions and considered part-time work, Evans kept his job at ESL Federal Credit Union. He has said he will step down from the bank before assuming the mayoralty.

The RCSD had already been limping from crisis to crisis before Evans joined the board, and there were few outward signs of improvement during his tenure. Tumult was the order of the day, as the district cycled through superintendents, grappled with budget deficits, fended off talk of mayoral control of the school system, and student achievement stagnated.

Six years into his tenure on the board, the state comptroller released an audit that found the school board had failed to protect the district’s financial interests from waste and abuse by past superintendents and their top aides, took little or no action to control tens of thousands of dollars in undocumented bonuses, and awarded millions of dollars in no-bid contracts.

Evans, who was the new president, at the time dismissed the findings as “old news” and said the board had since corrected its deficiencies, including ousting some top officials.

“It was very tumultuous, it was very volatile, there was a lot of interpersonal squabbling,” said Shirley Thompson, who was a school commissioner from 2000 to 2007.

Her time on the board was so toxic, she said, that she has tried to leave those days as a distant memory. But she recalled Evans as a thoughtful commissioner who shared her motivations of community service.

“Malik was a very solid board member,” Thompson said. “One of the things I liked about Malik was he was very approachable, and he was very present.”

When Evans joined the board, the district had an on-time graduation rate of about 55 percent. When he left in 2017, the rate was at 57 percent.

Today, he is ambivalent about his time on the school board. There were some good things — he points to Wilson Magnet being ranked 27th best high school in the nation by Newsweek in 2005 as a high point — but acknowledged that the issues he confronted have snowballed.

“The challenges the district faced were 50 years in the making even when I got there,” Evans said. “You had declining enrollment, you had high levels of poverty, and you had some folks that believed that, ‘Oh no, these kids can’t do it.’”

He added: “I always say that I wish there was more that could have been done, but I gave a lot of my formative years to the school board.”

A MAYOR IN THE MAKING

When Evans trounced Warren in the Democratic primary in June, effectively clinching the mayor’s job, his victory surprised many people.

After all, he was facing a two-term incumbent and a politician regarded by many to be coated in Teflon. At the outset of his campaign, political observers, including his friend, Gamm, publicly regarded his pursuit as an uphill battle.

But people closest to Evans were not surprised.

“Our father and mother wouldn’t be surprised. He said in the first grade that he wanted to be the president of the United States,” said his younger sister, LaShara Evans. “He laughs now and says, ‘I don’t want to be the president.’ But we knew he would always go into politics. And business, we knew he would go into banking as well.”

LaShara Evans is the principal of Flower City School No. 54. Her office has a floor-to-ceiling bookshelf adorned with family photos and mementos that reveal the closeness of the Evans family. She said she and Evans talk by phone twice a week.

Like her brother, she credited their parents for what success she and her siblings have found.

Lawrance Lee Evans Jr. is now the managing director of financial markets and community investment for the United States Government Accountability Office. Akilah Evans, the youngest sister, is a medical doctor in Syracuse.

But the Evans household isn’t all work and no play. The presumptive mayor-elect lives in the Cobbs Hill neighborhood with his wife, Shawanda, and their two boys, Cameron and Carter, with whom he said he finds time to play the now-vintage video games of his youth as well as more modern games in NBA 2K or Madden.

“That’s probably the biggest escape I have, my kids bragging and talking junk,” Evans said.

He said he’s grateful his boys enjoy football like him. But like other long-suffering Buffalo Bills parents, he’s shouldering the ultimate betrayal: his sons root for the Philadelphia Eagles and the Baltimore Ravens.

“They’re so disrespectful,” Evans said, jokingly. “But I’ll tell you, if the Bills win the Super Bowl, we’re shutting down the city.”

Evans met Shawanda during his early years in banking at a career day she had helped organize in the basement of Aenon Baptist Church. They would get married in the same church years later.

“She felt sorry for me,” Evans said. “I was doing a career day, she was running the career day, and she wouldn’t give me the time of day. And then someone said, ‘You know, I think he’s a nice guy.’”

On the campaign trail, Evans repeatedly promised a transparent and inclusive administration without ego. What he wants, he said, is to inspire not only his city, but his children.

“The biggest difference I want to make is the difference in the life of my kids,” Evans said. “I want them to know that their father did everything he could do to not only provide for them and make sure they were strong men and could provide for their family, but I also didn’t forget about the larger community.”

Evans said his job as mayor would be to pull together the city to tackle its challenges. After years in politics and public service, with more ahead, Evans waxes philosophical about his view of government.

“I wanted to make sure that the space I take up on this little planet, which we all take up, when you think about the planet, not to sound esoteric, but the planet is billions of years old,” he said. “All of us are but a speck in the span of the billions of years the Earth has been here. So what difference will you make?

“On my tombstone,” Evans went on, “I want it to say, ‘You know what? He tried.’”

CORRECTION: The original version of this story misidentified the church where Malik and Shawanda Evans met. The story has been updated with the accurate information.

Gino Fanelli is a CITY staff writer. He can be reached at (585) 775-9692 or [email protected].

Latest in News

More by Gino Fanelli

-

DeWolf Brewing Company set to open in Victor

Apr 26, 2024 -

These small cannabis farmers say New York's legal weed rollout is ruining their lives

Mar 21, 2024 -

Man shakes fist at sun

Mar 15, 2024 - More »