[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

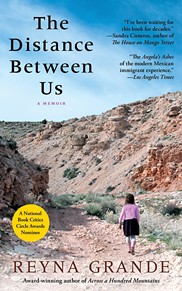

Writers & Books last year named "The Distance Between Us," a novel by award-winning author Reyna Grande, as the selection for its 2018 Rochester Reads program. In her memoir, Grande recounts her harrowing experience as a child living in Mexico in extreme poverty and her journey to the United States as an illegal immigrant. Grande will be visiting Rochester from March 28-30 for a series of readings, book signings, and book talks. Information on events, discussions, and workshops leading up to her visit can be found at wab.org. CITY spoke via phone with Grande in advance of her visit about her writing process and the experience that informed her book.

CITY: I'm curious about the difference between your writing processes from novels to a memoir — how do you maintain literary merit in a memoir?

Grande: I think the first draft of "The Distance Between Us" was a complete mess. Because I was coming from novel writing, that's what I knew how to do. When I started writing the memory I felt limited because I was writing about my own experiences. In the first draft there wasn't much dialogue because I couldn't remember word-for-word the conversations. I wouldn't let my characters speak. There was really no story arch because I was just writing down everything I could remember. Even though I didn't remember everything that had been said, I could use creative license to recreate conversations to the best of my knowledge and memory. What was important was maintaining that emotional truth in the story. I was able to tap into my imagination to create these moments and let my characters speak.

Capturing the voice of your inner child can require tremendous vulnerability. How did you find the voice of five-year-old Reyna? The little girl who points to her bellybutton to remember where she comes from?

Well, she's still inside of me. That's really how it is. Have you read Sandra Cisneros? The short story "Eleven," it says no matter how old you get there's still that nine-year-old inside you, that 10-year-old inside you, that five-year-old inside you. You fit like — you know those Russian dolls that fit inside each other? That's how she describes how we age. I find that to be very true. When I write, I don't have a hard time tapping into my five-year-old self, my 10-year-old self, my teenage self, because they're all inside me.

In the beginning of the book you mention the peso had been devalued 45 percent to the U.S. Dollar — and that was in young Reyna's account. These concepts are almost impossible for a child to grasp, yet they directly affected her world. What are some of the changes you're seeing now between U.S.-Mexico relations that continue to affect your hometown of Iguala?

Well I have to say that the biggest one is the drug addiction in this country has such a tremendous impact on my hometown. My home state of Guerrero grows fifty percent of the poppies for the heroin trade. My home state, and especially my hometown, is surrounded by poppy fields. There is the cartel and people are being forced to work in the poppy fields. That's why there's so much instability down there. The drug epidemic greatly affects Mexico and creates a lot of corruption over there because the drug market is probably the biggest source of income besides oil and remittances. It's a billion dollar industry. It creates a lot of corruption and violence.

What relationship do your children have with Iguala and with the traditions you knew there?

I take my kids every year to my hometown. I started a tradition five years ago where we go during the Christmas season to give toys to the kids there. So we've been going every year and give out around 700 toys or so. It's really nice for my children to see my hometown so they can see the poverty where I lived and where my family still lives. And I hope that makes them appreciate the things that I give them now. And what I have spared them.

Can you tell me more about some of the word choices you made? For example, in some of the dialogue, particularly in the beginning you kept a lot of the Spanish words.

Sometimes I just write it the way I hear it in my memory. My editor was really good about letting me keep those in Spanish. It was interesting that when I was adapting the version for young readers, my editor, she asked me to change the words into English. There's really not a lot of Spanish in the young adult version.

America doesn't have a national language. What might American, English-speaking readers gain from sounding out Spanish words, seeing their syntax on the page, even if they only vaguely understand them contextually?

You know, I know they say that we don't have an official language, it's pretty blatant that the language is English. That's why children who grew up in immigrant households are made to feel ashamed when they speak another language. It's really too bad because I wish at some point they would just pick the official languages as Spanish and English. They are the most commonly spoken languages here. A lot of the names in this country are Spanish — especially in parts that used to belong to Mexico. Names of cities and streets, they're Spanish. I write in English, I always write in English, but I try to include some Spanish in there, to acknowledge that I'm bilingual and honor my mother tongue.

How does the novel help improve the various, harmful stigmas of illegal immigrants?

Well, I think that when you hear politicians talk about immigration, a lot of times the issue is discussed in terms of politics or the economy. It's also important to keep in mind that we're talking about human beings. When I wrote this book, I was writing for readers who do not have a lot of information, to get an insight. Make people think about what counts as immigration and why people leave their homes behind. I feel that when people are allowed to come here as refugees it's mostly because of war or a political situation they were involved in, but an economic refugee is looked down upon.

Poverty is a consequence of this capitalist society that we live in and a very uneven society where few people have a lot and a lot of people don't have much. There are places like Mexico and a lot of other countries where a lot of people don't have much and a lot of times they're victims to their governments but also foreign governments that come in and create instability; economic instability especially. So I guess for me it's just writing about my experience with poverty and how that led to all of the things that happened with my family.

Right now, one of the ways in which readers gauge a book is by its socio-political impact. "The Distance Between Us" has been described as an "important read" — why do you think that is?

I think it's important to read the book because we're still dealing with the situation, especially right now that we're talking about the young, undocumented immigrants living here, figuring out what to do with them. We seem to be taking a long time making the right choice. One of the differences between me and the Dreamers is that I was very fortunate to have been able to legalize my status while I was still a teenager. Because of that opportunity, I was able to do all of the things that I did and reach my dreams and accomplish everything that I had set out for myself. I think that the Dreamers could go on to do all of those wonderful things if we gave them a chance.

Did you watch President Trump's recent State of the Union address? Immigration was a major focus.

I really feel that it's not that difficult to make that decision, to pass immigration reform that will open the door for young immigrants. I feel that there's something going on in this country where we don't seem to do our best for young people. No matter if they're immigrants or citizens. We're failing our young people by not giving enough to education, cutting school budgets. If that's the way we treat U.S. citizens, I'm not surprised that's how undocumented youth are being treated.

The memoir notes the vastly different struggles that exist in Mexico versus those in the States. But some of the most touching moments in "The Distance Between Us" are those that everyone can relate to: sibling rivalry, favoritism, jealousy, or just wanting to make your parents proud. How does the memoir connect all readers to the Grande family?

I feel the poverty part is something that readers can relate to because there are a lot of poor people in the U.S. even though we don't want to talk about it. But there's a lot of poverty here. Also family dysfunction, it's an experience that many people can relate to. I think that's something that affects all cultures. And then the experience and being a young person and trying to figure out your place in the world. I think that's also universal.

The sequel comes out this year. Is there anything you can tell us that we can look forward to in that memoir?

I'm always being asked: what happened after? When I do school visits and readings, that's always the question people ask me. I thought that I would write this book because a lot of Latino literature is focused on the teenage years. But there's not a lot that focuses on the college years. Students of color have a different experience in college than white students. Junot Díaz wrote an essay called "MFA vs. POC" and he writes about that experience. I guess the theme of the book is my search for a home and belonging. The second story line in there is about my pursuit of my writing dream. It's about my search to belong and trying to find the home that I had longed for all these years and realizing that I was going to have to build my own home because nobody else was going to give it to me.

Speaking of...

Latest in Culture

More by Rachel Crawford

-

Nine new books we’re excited to read this fall

Sep 1, 2021 -

Political disquiet

Feb 26, 2020 -

ART | 'Genesee Valley 100'

Dec 11, 2019 - More »