[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

It would seem that even a well-made guitar has no soul; it is merely wood and wire. But in music's endless pursuit to get what is in the musician's heart into the listener's ear, the guitar is an important vessel, or at the very least a bridge in this quest.

It's true that the instrument is only as effective in this pursuit as its player, but there are guitar builders — technically called luthiers — who pour their own hearts and souls into the creation of these instruments, these tools. And whereas the musician wrestles with the perfunctory theory of sharps and flats and notes and scales, the luthier struggles to balance aesthetic beauty with required functionality. The instrument must be pleasing to the eye and to the ear. It's an artistic endeavor over and above the actual construction of a musical item.

City talked with five local guitar builders to discuss the passion and innovation that goes into a boutique-made guitar. We discussed art versus function, innovation versus tradition, and falling in love with a creation before setting it free.

Robert Mortillaro

Mortillaro Customs | [email protected]

It takes time to build a beautiful guitar, especially if you're busy fixing other people's instruments. Because of his workload, guitar builder and repairman Robert Mortillaro only builds one or two custom-ordered guitars per year.

"A Telecaster-type electric guitar I can finish in a weekend," he says. "A flat-top guitar can take anywhere from a month to six months. The most elaborate guitar I built was for my brother for his graduation — graduation from high school. But I kept adding things onto it, so it became graduation from college."

Mortillaro, who has worked as a repair and set-up luthier at Bernunzio Uptown Music for 10 years, began building his own guitars in 2005.

"I started building mostly solid-body electric guitars," he says. "About a year later I really got into building acoustic flat tops." But he wasn't taking orders, they were all for him.

Mortillaro holds a master's degree in fine arts. "For my thesis at RIT I built a mandolin, a flat-top guitar, and an electric guitar," he says. "It was really a nice sense of accomplishment to see an idea develop into something that was tangible." And he admits to growing attached to the fruits of his labor.

"The first few I ended up hanging on to," Mortillaro says, "because I didn't want to get rid of them." Now he sells the instruments he creates for $750 to $3,000 a pop.

Though Mortillaro adheres to the tradition of working with wood on classic designs, he still looks to explore and innovate, as he did with his carbon-fiber archtop guitar.

He enjoys "going outside the box with something a little bit off the wall, something that no one had tried yet, and trying to make that a reality," he says. "It's a balancing act, like trying to get the electronics to balance with the acoustics, to work out all the kinks."

Bernie Lehmann

Bernie Lehmann started building mountain dulcimers after graduating from Syracuse University in 1972. "They were simple," he says. "Honestly, I didn't know what one was, but I wanted to make stringed instruments and they looked like something fairly simple to get going on and learn the basic processes. I would eventually move to guitars."

Lehmann builds about a dozen instruments annually: flat tops, archtops, gypsy, and classical guitars, as well as mandolins and ukuleles, and lutes and Medieval-style fiddles. He even builds a weird hybrid instrument he dreamed up with musician Laurence Sugarman, simply called the munjo.

"It's got a mandolin body with a five-string banjo neck on it," says Lehmann. "And it has a Viking head carved into the headstock and it has a domed, lute-like back."

Though Lehmann focuses mostly on flat-top guitars, all of his creations are functioning works of art. They sound as good as they look. The lush, supple woods, the exquisite hardware, the patina and mirror gloss of their finish give the instruments the look of fine furniture. The appearance is captivating, but Lehmann stresses the priorities.

"Function and tone come first, but art is extremely important to me," he says. "And I think the two can be combined. I'm always willing to experiment and see what I can get away with."

Lehmann has played around with innovations like installing second sound boards in a guitar to help brighten the response. He has also installed upper sound ports to bring more tone and sound up to the player's ears.

Lehmann estimates that he puts roughly 80 to 100 hours into a basic flat-top guitar — and that's the minimum. A Lehmann guitar will cost between $4,000 and $15,000. And in those long hours he's been known to grow attached and fall in love with some of his projects. It can be hard to let go.

"It is very hard," he says. "I get very attached to them. That's part of the beauty for me, instilling myself into it, making each one a unique piece of functional art."

Greg Bogoshian

RockBeach Guitars | rockbeachguitars.com

Twelve years ago, Greg Bogoshian was playing in a group called Circle of Friends at Covenant United Methodist Church. Up to that point, he'd never built so much as a birdhouse out of lumber. But after stumbling upon some gorgeous planks of African Padauk at Pittsford Lumber, Bogoshian was moved to action.

"I'd never seen wood with that color, that grain to it," he says. "I said, 'I have to do something with it.' I'd never built anything with wood before."

Bogoshian had played acoustic, but thought it was time to switch to electric. So he built an electric guitar, drawing upon his 38 years of experience as a technician at Xerox.

"I kind of used those skills, experiences, and techniques to develop my process for construction," says Bogoshian. "And I used my instincts for what would sound good. I wanted to do it right."

There is no mistaking a RockBeach guitar. They're radical enough to be different, but not so much so that they no longer look like a guitar. The problem, according to Bogoshian, is players typically and stubbornly go for what they know — the Stratocasters, the Telecasters, the Les Pauls, and the SGs of their heroes. RockBeach guitars look different, not just for aesthetic reasons, but out of functionality. The beautiful woods are layered for durability and sustainability, and the body of the guitar is hollowed out or "channeled," adding tone while at the same time reducing weight. The bottoms of the Cicada and Mantis models are split to go on the player's leg as opposed to having the instrument slip and slide around on their lap.

"Ergonomics are very important to me," Bogoshian says.

Bogoshian builds roughly four to five guitars per year, spending anywhere from 75 to 300 hours on each, depending on complexity. A RockBeach guitar will typically run in the $1,300 to $2,800 range. Despite the time he spends with each piece, Bogoshian has no problem letting them go.

"These guitars belong in more competent hands than mine," he says.

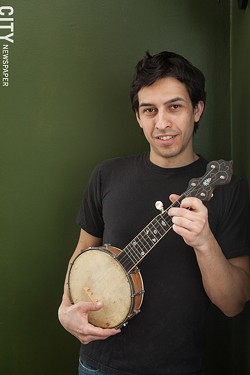

Beau Leopard

BL Design | bldesign.us

Beau Leopard started playing bass at 14 and quickly discovered he wanted more than was available out there. "About a year later I wanted a better bass," he says. "I was interested in playing a five-string like I saw in magazines. I just wanted something more interesting."

"I grew up building stuff with my father, mainly skateboard-related things," Leopard says. "He suggested I build a bass. So I did. I bought the neck pre-made, but I built the body. I had some help from local banjo builder Richard Newman, who was a friend of my father, with things like cutting the neck pocket out. As I went further down the road, it got quite involved."

In 2005 Leopard began building in earnest, basing his designs on the playability he required and the high-end instruments he saw advertised and at shows, like Les Claypool's custom bass built by Carl Thompson.

He focused on rare, high-end woods and intricate designs without forgoing the playability. "I think at first it was about appearance," says Leopard. "And as the years went on it became more about function. Even the second and third basses I built in shop class in high school were pretty exotic. Early on I was blown away by the aesthetics of it."

As a builder, Leopard finds satisfaction in filling a void. "I like to see what a client wants that they can't get out there," he says. "Something that they haven't been able to find. It gets pretty specific, like the distance between the bottom of the string and the top of the instrument for those players who slap, is sort of critical. Overall, the most important thing is how it feels, how it balances. There's not a lot out there that feels like my stuff does. There's a lot of eye candy involved, but when you take that all away, it's really about a high-performance instrument."

His customers are willing to forgo tradition to achieve this performance.

"Granted," says Leopard, "the p-bass [precision bass] and the j-bass [jazz bass] are the staple instruments. But I think bass players are a little more willing to take risks as far as custom instruments."

Leopard builds about four basses a year with 120 hours put into each one, not including client consultation time. His basses cost between $3,000 and $7,000. Despite the somewhat steep price tag and some musicians' fear of the new, Leopard helps boost sales and awareness by encouraging test drives of his equipment at various open jams in the area, where he sets up hands-on displays of his work.

"I put everything I have into these things, so sure, it's tough to let go of them," he says. "But it helps when they go to great players. I've sold some basses in Rochester, but the main market is mostly in major cities. I have had good luck in Toronto, L.A., New York."

Ben Bruton

Bruton Guitars | brutonguitars.com

Ben Bruton was a funky rock 'n' roller in the Rochester-based band 11 Ft 7 during the 1990's. After that band went six feet south, he discovered that he was equally handy with the tools he used to build guitars, which allowed him to remain involved in the music scene.

"When the band decided to call it quits," Bruton says, "I was like, 'What am I going to do now?' That was kind of my biggest ambition. So I decided to marry the two talents I had so I could stay in music somehow. And with the wood-working skills and the music I thought, 'Hey, you know what? Maybe I can venture into a business with this.'"

Bruton started his business back in 2008, but he built his first guitar in 1998, and took it on the road for four years. Bruton perfected his luthier skills as an intern with Bernie Lehmann for a year and a half. That helped him to implement the features he desired as a player, in addition to meeting the demands of his clients.

"They were things I wanted as a player," says Bruton. "But it wasn't exclusive. As I started to build more for people, their input was very important. But a lot of that had to do with details like how it was set up and the finer points. But the actual model shapes and things like that were just really things that appealed to me."

The appeal is both aesthetic and tangible to Bruton. "I think it's a magic combination of both," he says. "It's functional art, when you come right down to it."

At his highest point of productivity Bruton figures he was probably building 12 guitars annually. It varies year to year.

"It's not a ton," he says. "But I'm staying busy."

He figures he can bang out one of his simpler models in less than a week. The fancier guitars take a while longer. "For some of my more complicated models, like my full archtop body style, that takes up to three weeks," he says. A Bruton custom will cost you between $1,300 and $3,900.

Bruton dismisses his own innovation as the innovation of all luthiers. For him, it's all about the relationship between creator and player.

"Builders all strive for the same thing," he says. "Great playability, great sound, great tone. On an individual basis, it's a relationship thing with my customers. When they want something built that's specific to them, it's sort of a joint venture, a collaborative effort to some extent. I think the chemistry between me and my clients sets me apart in some ways. I'm just happy seeing someone get it and know that they're satisfied. That's their baby and they're going to be playing it like crazy."