[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

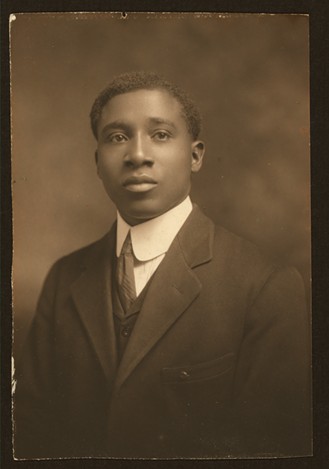

In 1937, radio listeners across the country heard a live performance of “The Ordering of Moses,” the defining composition of R. Nathaniel Dett, the first Black graduate of the Eastman School of Music, over the NBC Radio Network.

But 40 minutes into what was to be an historic hour-long broadcast — one of the first new compositions by a Black classical composer to be aired nationally — an announcer broke in:

We are sorry indeed, ladies and gentlemen, but due to previous commitments, we are unable to remain for the closing moments of this excellent performance.

No other explanation was given, but the prevailing theory was that NBC caved to complaints from listeners who objected to the broadcasting of music by a Black composer.

Eighty-five years later, Dett’s music and the story behind it are poised to be heard like never before thanks to the research of Jeannie Guerrero, a Rochester-based music theorist who has spent more than a year painstakingly updating “The Ordering of Moses” with more than 1,000 edits, including restoring orchestral interludes that she says are key to experiencing the full expressive power of the work.

She has filled in areas that Dett had left in shorthand, addressed parts that conflicted, and used notation software to create a piece more easily readable than the handwritten sheet music that has been used in previous performances.

This music is scheduled to be performed in October by the Rochester Oratorio Society, Roberts Wesleyan Chorale, and the Nathaniel Dett Chorale from Toronto.

“No one owns his narrative,” Guerrero says of Dett. “He owned his narrative. He's gone now. We don't know what's in his head. We can only try to make the most informed decisions that we can about performing his music, about telling his story, honoring his legacy. That's all we can do.”

Guerrero has also been tracing Dett’s life in Rochester, through archives, old newspapers, and other historical records to re-introduce Dett to Rochester and fill in the scattered historic record of the man and his legacy.

By the time Dett came to Rochester in 1931 to study at the Eastman School of Music, he was already an accomplished musician with some international celebrity. He had toured Europe as a conductor, received honorary degrees from Howard University and Oberlin College, and studied under the foremost teacher of 20th-century American composers, Nadia Boulanger.

Indeed, his enrollment at Eastman was enough to make headlines in the Democrat and Chronicle, which reported his arrival with qualified praise: “He is one of the most promising Negro composers of the day.”

Dett had also earned this reputation with compositions that incorporated Black spirituals. He described in a 1918 profile in the magazine Musical America:

Guerrero believes being a minority in a predominantly white field heavily influenced Dett’s decision to earn a degree from Eastman.

“I have to speak as a woman of color — and even a woman of not even much color — you always are striving to be better,” she says. “Because you never feel that you will be good enough to be accepted. And so having many, many degrees is really a minimum requirement to get anywhere.”

After finishing his degree, Dett stayed in Rochester, becoming involved in the city’s musical and civic life while expanding “The Ordering of Moses.” He wove in elements of the spiritual “Go Down Moses” and references to George Frederic Handel’s “Messiah,” going beyond combining genres to express mystical, universalist ideas about the shared human experience.

When Dett died at the age of 60 in October 1943, while on tour with a U.S.O. Women’s Army Corps chorus in Battle Creek, Michigan, the Democrat and Chronicle reported his death, praising his accomplishments, international recognition, and influence. As with the reporting of his arrival in Rochester, though, both the obituary writer and his teacher, Eastman School of Music Director Howard Hanson, qualified their admiration in terms of Dett’s race:

“I think, without question, that oratorio is the greatest chorus for Negro voice yet written,” Hanson was quoted as saying of "The Ordering of Moses." “In my estimation, he was one of the greatest composers of Negro music.”

Guerrero and local historian Arlene Vanderlinde are scheduled to present details of Dett’s life in Rochester in a talk at the Pittsford Community Library on Feb. 24 at 6:30 p.m., accompanied by performances of several of Dett’s shorter choral works.

“It can be surprisingly simple on the page, but it does lift you to some other plateau that you didn't really know you had when you started working on the thing,” Rochester Oratorio Society Artistic Director Eric Townell says.

Townell had first encountered Dett’s music in the 1990s in the archives of the Center for Black Music Research in Chicago, starting with the short choral piece, “Listen to the Lambs.” But only recently has Townell felt ready to take on the emotionally and technically complex “The Ordering of Moses,” accompanied by a choir named for the composer.

Having seen so few people of color represented in the world of Canadian choral music, Brainerd Blyden-Taylor founded the Nathaniel Dett Chorale 24 years ago with a focus on performing Afrocentric music. “The burden started to be laid more and more in my heart to do something,” he says.

But he needed a name that would represent Black Canadian history. A friend compiling an encyclopedia of Canadian musicians brought R. Nathaniel Dett to his attention.

“The more I learned, the more he seemed the perfect person to honor and to make Canadians aware of, and — I guess now almost 24 years later, by extension — to make a lot of people around the world aware of him, including some of my American brothers and sisters,” Blyden-Taylor says.

Marrying two traditions

Dett was born and spent most of his early childhood in Drummondville, Ontario, a historic refuge for people who fled slavery that is now part of Niagara Falls. He and his family moved over the border into the United States when he was 11.

As a youngster, he heard his grandmother sing spirituals and took piano lessons, studying Beethoven and other European classics. But it was not until he was a student at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music in Ohio that he first had the idea of blending these musical worlds.

“He seems to honor both traditions,” Blyden-Taylor says of Dett’s music. “He's married them quite well in my estimation.”

Emmett Tross, the New York City-based tenor who is preparing to sing the title role of Moses, described the piece as “a refreshing scent of home mixed with some beautiful eccentric and other-worldly experiences in a musical sense.”

Tross grew up in Rochester, where he was a student at School of the Arts, and studied music through the Eastman Community Music School. Ever since he was a young student, he’s felt a kinship with Dett as a Black classical musician.

“He kind of bridges that gap between the European artistic style of writing and the African-American influence in music in America,” Tross says. “Being able to put that on paper was extremely important for the advancement of said music being seen as non-barbaric or overzealous or bombastic, but allowing for it to be seen as what it was, which was absolutely gorgeously beautiful music that was created out of such a struggle — and happy times and terrible times and beauty and the many faces of the African American experience in America — which bleeds into everyone else's experience.”

Mona Seghatoleslami is an announcer/producer for WXXI Classical 91.5, and serves on the board of fivebyfive. She can be reached at [email protected].

But 40 minutes into what was to be an historic hour-long broadcast — one of the first new compositions by a Black classical composer to be aired nationally — an announcer broke in:

We are sorry indeed, ladies and gentlemen, but due to previous commitments, we are unable to remain for the closing moments of this excellent performance.

No other explanation was given, but the prevailing theory was that NBC caved to complaints from listeners who objected to the broadcasting of music by a Black composer.

Eighty-five years later, Dett’s music and the story behind it are poised to be heard like never before thanks to the research of Jeannie Guerrero, a Rochester-based music theorist who has spent more than a year painstakingly updating “The Ordering of Moses” with more than 1,000 edits, including restoring orchestral interludes that she says are key to experiencing the full expressive power of the work.

She has filled in areas that Dett had left in shorthand, addressed parts that conflicted, and used notation software to create a piece more easily readable than the handwritten sheet music that has been used in previous performances.

This music is scheduled to be performed in October by the Rochester Oratorio Society, Roberts Wesleyan Chorale, and the Nathaniel Dett Chorale from Toronto.

“No one owns his narrative,” Guerrero says of Dett. “He owned his narrative. He's gone now. We don't know what's in his head. We can only try to make the most informed decisions that we can about performing his music, about telling his story, honoring his legacy. That's all we can do.”

Guerrero has also been tracing Dett’s life in Rochester, through archives, old newspapers, and other historical records to re-introduce Dett to Rochester and fill in the scattered historic record of the man and his legacy.

By the time Dett came to Rochester in 1931 to study at the Eastman School of Music, he was already an accomplished musician with some international celebrity. He had toured Europe as a conductor, received honorary degrees from Howard University and Oberlin College, and studied under the foremost teacher of 20th-century American composers, Nadia Boulanger.

Indeed, his enrollment at Eastman was enough to make headlines in the Democrat and Chronicle, which reported his arrival with qualified praise: “He is one of the most promising Negro composers of the day.”

Dett had also earned this reputation with compositions that incorporated Black spirituals. He described in a 1918 profile in the magazine Musical America:

We have this wonderful store of folk music, the melodies of an enslaved people, who pour out their longings, their griefs, and their inspirations in one great universal language. But this store will be of no value unless we utilize it, unless we treat it in such a manner that it can be presented in choral form, lyric and operatic works, concertos and suites and salon music — unless our musical architects take the rough timber of Negro themes and fashion from it music that will prove that we, too, have national feelings and characteristics, as have the European peoples whose forms we have zealously followed for so long.

Guerrero believes being a minority in a predominantly white field heavily influenced Dett’s decision to earn a degree from Eastman.

“I have to speak as a woman of color — and even a woman of not even much color — you always are striving to be better,” she says. “Because you never feel that you will be good enough to be accepted. And so having many, many degrees is really a minimum requirement to get anywhere.”

The Ordering of Moses

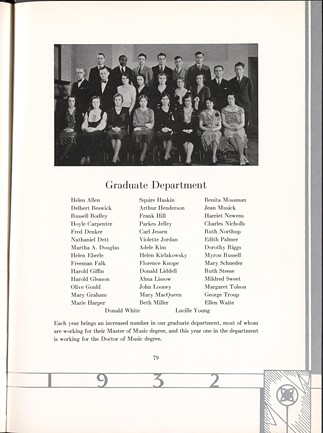

Dett wrote the beginnings of what would become his magnum opus, the oratorio “The Ordering of Moses,” for his master’s thesis. Written for orchestra, chorus, and soloists, the piece is a poetic, expressive retelling of Moses receiving a message from God and leading the Israelites out of captivity in Egypt and into the promised land. The vocalists sing of prophecy and vision, struggle and freedom. This music was performed in its initial form at Eastman in June 1932.After finishing his degree, Dett stayed in Rochester, becoming involved in the city’s musical and civic life while expanding “The Ordering of Moses.” He wove in elements of the spiritual “Go Down Moses” and references to George Frederic Handel’s “Messiah,” going beyond combining genres to express mystical, universalist ideas about the shared human experience.

When Dett died at the age of 60 in October 1943, while on tour with a U.S.O. Women’s Army Corps chorus in Battle Creek, Michigan, the Democrat and Chronicle reported his death, praising his accomplishments, international recognition, and influence. As with the reporting of his arrival in Rochester, though, both the obituary writer and his teacher, Eastman School of Music Director Howard Hanson, qualified their admiration in terms of Dett’s race:

“I think, without question, that oratorio is the greatest chorus for Negro voice yet written,” Hanson was quoted as saying of "The Ordering of Moses." “In my estimation, he was one of the greatest composers of Negro music.”

Guerrero and local historian Arlene Vanderlinde are scheduled to present details of Dett’s life in Rochester in a talk at the Pittsford Community Library on Feb. 24 at 6:30 p.m., accompanied by performances of several of Dett’s shorter choral works.

Singing Dett's legacy

With the piece newly edited by Guerrero in hand, the Rochester Oratorio Society, Roberts Wesleyan Chorale, and the Nathaniel Dett Chorale are preparing to perform “The Ordering of Moses.”“It can be surprisingly simple on the page, but it does lift you to some other plateau that you didn't really know you had when you started working on the thing,” Rochester Oratorio Society Artistic Director Eric Townell says.

Townell had first encountered Dett’s music in the 1990s in the archives of the Center for Black Music Research in Chicago, starting with the short choral piece, “Listen to the Lambs.” But only recently has Townell felt ready to take on the emotionally and technically complex “The Ordering of Moses,” accompanied by a choir named for the composer.

Having seen so few people of color represented in the world of Canadian choral music, Brainerd Blyden-Taylor founded the Nathaniel Dett Chorale 24 years ago with a focus on performing Afrocentric music. “The burden started to be laid more and more in my heart to do something,” he says.

But he needed a name that would represent Black Canadian history. A friend compiling an encyclopedia of Canadian musicians brought R. Nathaniel Dett to his attention.

“The more I learned, the more he seemed the perfect person to honor and to make Canadians aware of, and — I guess now almost 24 years later, by extension — to make a lot of people around the world aware of him, including some of my American brothers and sisters,” Blyden-Taylor says.

Marrying two traditions

Dett was born and spent most of his early childhood in Drummondville, Ontario, a historic refuge for people who fled slavery that is now part of Niagara Falls. He and his family moved over the border into the United States when he was 11.As a youngster, he heard his grandmother sing spirituals and took piano lessons, studying Beethoven and other European classics. But it was not until he was a student at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music in Ohio that he first had the idea of blending these musical worlds.

“He seems to honor both traditions,” Blyden-Taylor says of Dett’s music. “He's married them quite well in my estimation.”

Emmett Tross, the New York City-based tenor who is preparing to sing the title role of Moses, described the piece as “a refreshing scent of home mixed with some beautiful eccentric and other-worldly experiences in a musical sense.”

Tross grew up in Rochester, where he was a student at School of the Arts, and studied music through the Eastman Community Music School. Ever since he was a young student, he’s felt a kinship with Dett as a Black classical musician.

“He kind of bridges that gap between the European artistic style of writing and the African-American influence in music in America,” Tross says. “Being able to put that on paper was extremely important for the advancement of said music being seen as non-barbaric or overzealous or bombastic, but allowing for it to be seen as what it was, which was absolutely gorgeously beautiful music that was created out of such a struggle — and happy times and terrible times and beauty and the many faces of the African American experience in America — which bleeds into everyone else's experience.”

Mona Seghatoleslami is an announcer/producer for WXXI Classical 91.5, and serves on the board of fivebyfive. She can be reached at [email protected].

Speaking of...

Latest in Music Features

More by Mona Seghatoleslami

-

Our 10 favorite Rochester albums of 2022

Dec 21, 2022 -

Gateways Music Festival returns, with some changes

Mar 21, 2022 -

Andreas Delfs brings holiday tradition of 'Hansel and Gretel' to RPO

Nov 19, 2021 - More »