[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

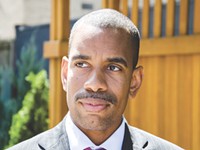

You're afraid of Bill Johnson.

You're afraid, Pittsford, that Bill Johnson wants to put city kids in your schools.

You're afraid, Fairport, that Bill Johnson wants to steal your wallet and give its contents to the city.

You're afraid, Chili, that a city mayor can't possibly have the interests of the suburbs at heart.

Bill Johnson is black. And you're afraid.

Right?

"In general, I think everybody believes the community-at-large is better than that," says Travis Heider, spokesperson for Johnson. "It would be ignorant to say it's not an issue for some."

The Monroe County executive race is the single most important local election in recent memory. It comes at a crossroads in the county's history. Faced with large deficits, high taxes, youth flight, and a dearth of jobs and opportunity, the county has hit a fork in the road. Down one path lies prosperity and rebirth. Down the other, failure and ruin. Our next county executive will either pilot the Spirit of St. Louis or the Edmond Fitzgerald.

The race is historic in another way that has gone largely unmentioned. That is, until a former local radio host opened his big mouth and out popped the elephant everybody pretended wasn't there.

I think we all know what Bob did, but his irreverence and cutting-edge humor are part of his appeal. I hope this turns out OK for him, but somehow, I feel like things have changed forever. [letter to www.boblonsberry.com, Bob Lonsberry's website]

Some say race is a major factor in the county executive race. Others think race is one of many factors, but certainly not the primary one. Still others say race doesn't matter at all.

"It's not like it's new news that Bill Johnson is black," says county Democratic leader Molly Clifford. "It's not something we hide."

The color of Johnson's skin may not influence the campaign, Clifford adds, but it might effect how people vote.

Monroe County's population, according to census figures, is almost 80 percent white. The suburbs are more than 90 percent white. Whites are the single largest race in the city, but Rochester is a majority nonwhite city.

What does that mean?

"Given the stark segregation in residential patterns in the county and other indicators, race without question has some effect on politics and the behavior of whites in Monroe County," says Christian Grose, professor of political science at Lawrence University in Appleton, Wisconsin.

Grose earned his Ph.D. in political science from the University of Rochester. He is a specialist in the study of race and politics and has been following the race for county executive. Grose is co-author of "Black Mayors, White Cities," a paper analyzing the extent of racial polarization in voting in the 1993 Rochester mayoral primary.

Johnson, Grose concludes, has proven crossover appeal. In the 1993 Democratic primary, Johnson won a plurality of non-black votes, nearly 29 percent. At the time, Rochester was a majority white city. Overall, Johnson won 32.4 percent of the vote.

Ruth Scott, another African-American in the race, won nearly 22 percent of the total vote. Nancy Padilla, a Latina, won 5.3 percent.

"Here was a city that was able to look beyond race and cast a significant majority of its votes for nonwhite candidates," Johnson says. "To me, that shows what kind of community this is."

"Johnson can win the county executive race if he can draw support from non-black voters, as he did in his first mayoral primary, and also count on black voter support," Grose says. "The question is, are white voters in the city of Rochester the same as white voters in the suburbs? I would say no."

The fact that the suburbs have seen Johnson in a public leadership role helps him, Grose says. But suburbanites' lack of exposure and interaction with minorities allows underlying racial animosity some suburbanites might harbor to surface.

"The bottom line is, the conservative white constituency is running someone [Republican candidate Maggie Brooks] who is popular and white," Grose says. "Any Democrat [in Monroe County] has an uphill battle. A black candidate has a particularly difficult battle."

It's getting to the point that we cannot look at a black person cross-eyed without being labeled. [letter to www.boblonsberry.com]

It's all about fear, and county Republicans are fanning the flames, Johnson says.

"I believe that neither Maggie Brooks nor I attempted to capitalize on either our race or gender," he says. "You never heard me going around campaigning, 'I wanna become the first African-American county executive in Monroe County.' I haven't heard her say she'll be the first female. It'd just be obvious."

That being said, however, Republicans are purposefully distorting his position, Johnson says. By repeatedly linking Johnson with metro government, the GOP is playing on people's fears of the city, he says.

"The race issue has morphed into the consolidation issue," Johnson says. "Maybe, early on, they recognized that this generally evoked so much fear, they saw it as an effective campaign strategy."

Despite the fact that he has repeatedly said that he has no consolidation plans and couldn't combine city and county schools and governments even if he wanted to, it is still the first question he's asked at every public appearance, Johnson says.

Republicans are pushing their message, he adds, through WHAM 1180. Former host Bob Lonsberry was a particularly effective tool, Johnson says, until his firing earlier this week.

You can call me a Ho if you want. I'm not a Ho, so I'll laugh it off and get on with my life. Call someone a monkey, however, and the city goes to pieces. If the one offended didn't relate to being a monkey, the comment wouldn't upset him. [letter to www.boblonsberry.com]

Racism, Johnson says, had not been a factor in his political career until last week, when it was reported that former WHAM 1180 host Bob Lonsberry said over the air that a monkey was running for county executive.

"Orangutan escapes from zoo, runs for county executive," were Lonsberry's now infamous words.

What followed was a firestorm of press conferences. Politicians on both sides of the aisle, members of the local clergy, and other organizations expressed shock. Some, including some local Republicans, called for Lonsberry's dismissal or resignation. Lonsberry was suspended. He apologized and agreed to undergo diversity training. But public pressure mounted and WHAM finally agreed dump Lonsberry on Monday.

"After Mr. Lonsberry made inappropriate comments on the air, he convinced us that he was willing to face his mistakes and learn from his behavior," reads a press release from the station. "Although Mr. Lonsberry expressed willingness to change, it became obvious to us that he is not embracing diversity or the beliefs of the station."

The city and the station, Johnson says, have been suffering from a bad case of myopia. People were distracted by Lonsberry's words, he says, and not paying attention to his strategy: to work with Republicans to defeat Johnson any way they can. Johnson cites appearances by Brooks and other prominent Republicans on Lonsberry's show as proof.

"Bob Lonsberry has essentially been pushing their agenda through his show," Johnson says. "He has been blistering in his views about consolidation and they have essentially, through that mechanism, been able to transform consolidation into a code word; a word that instinctively engenders fear. It's been a powerful, powerful tool."

"It's not out-and-out," Johnson adds. "He's not on there using the 'N' word. He's not on there raving racial issues. But they have, I believe, very cleverly developed this issue in such a way that, if nothing more, calls up very primitive fears of the thing we call the city and all that's associated with it."

Simply put, according to Johnson, the Republicans' message to the suburbs is this: "Vote for Bill Johnson and all the city's perceived problems will darken your doorstep."

Brooks reacts with incredulity to this.

"That's absolutely ludicrous," she says. "That's not the case. The metro government issue threatens people because it threatens their choice of where they can live and where they can send their kids to school. It has nothing to do with racial undertones. I have to question why the Democratic Party would politicize race. It's too important of an issue to be injecting it into a political campaign or suggesting that one party is doing these subtle racist things. There's no place for that in this campaign."

Neither race nor gender are factors in the campaign, Brooks adds.

"I think this is clearly a race about leadership and about the future of the community and about change," she says. "[People] are looking for someone who is going to talk about issues that matter, like economic development and jobs and stable taxes. And I think we have the right message and the right vision for Monroe County, and we're getting a great response."

You all hide behind a mask of debunking political correctness because you want to be free to say what's in your hearts because you want to be cruel. [letter to www.boblonsberry.com]

The Lonsberry episode probably doesn't help Johnson much in the long run, experts say, because the election is still more than a month away. But it could raise his profile in the suburbs.

"In some ways, it does make Johnson more visible. Johnson's campaign has not been as loud or as strong as I think a lot of people expected it to be," says Timothy Kneeland, history and political science professor at Nazareth College. "What that does to motivate voters in the suburbs, I don't know. It could electrify some of the Democratic voters in the city who might feel strongly he's being victimized."

Indeed, Johnson says, he's already seen a little of that borne out.

"I've had people call me up and say, 'Bring me a lawn sign. I wasn't gonna vote for you before, but bring it out here,'" he says. "I'm human like everybody else. I'll take whatever gifts are given to me."

Race is a factor in the campaign, Kneeland says, but it's not the only one. Race aside, he says, there's always a question of competition between urban and suburban areas.

To ease fears suburbanites may have, Johnson needs to get out into the suburbs and to "saturate the county" with ads touting his leadership accomplishments, Kneeland says.

"He needs to make himself the visible candidate, so people can say, 'I can see him leading the county,'" he says. "There's no clear message from his campaign. He's got to get suburban people to start paying attention."

Race is slippery and subtle, Kneeland says, and, as previously mentioned, is tied into consolidation, taxes, class, and other issues.

"It's not been an overt part of the race, just since the Lonsberry thing," he says. "There are very few Archie Bunkers left."

Bottom line: Does Monroe County elect a black man, a Democrat nonetheless, county executive?

"I'd be very surprised to see an African-American get a majority of votes in the suburbs," says Harry Murray, sociology professor at Nazareth. "But I don't want to say it's impossible. There are still a lot of subtle types of racism that people aren't quite conscious of. When push comes to shove, race will enter in."

Brooks, Murray says, doesn't face the same problem with minority city voters.

"I think African-Americans are more used to voting for whites than whites are used to voting for African-Americans," he says. "Historically, they haven't had that much of a choice."

Brooks poses another problem for Johnson, Grose says: the gender gap. White suburban women are more likely to vote for a black man than their male counterparts are, he says. But with Brooks in the race "white women might identify with her and swing a few votes her way."

Johnson, Grose says, needs to implement a dual strategy: increase black turnout in the city, but don't mention race in the suburbs.

"It's possible," Grose says. "But it's hard to do."

Most suburbanites interviewed for this article said Johnson's record, not his race, is the determining factor.

"I have a lot of respect for Bill Johnson," says Pittsford resident Chris Ramsey. "I don't always agree with him. I don't agree with his politics. But it has nothing to do with race. The fact is, he's the Democratic candidate. [The] suburbs are heavily Republican. That's gonna be his hurdle."

Greece resident John Smith said there's no way whites will let Johnson win in the suburbs.

"They want their own race," he says. "They think colored people are dirty and unresponsive."

And what does Johnson have to say about all this? Does Monroe County elect a black man county executive?

"It'd be the first time," he says. "If I didn't think it were possible, I wouldn't be in this race. I'm no masochist. The test is gonna be in November. What, 90-92 percent of people, non-city residents, are white? So I gotta win a substantial portion of those votes in order to win.

"I'm also perfectly prepared in the event it doesn't happen," he adds. "I wouldn't be going and blamin' it on race, either."

The truth about schools

One of the issues that comes up repeatedly in the county executive race is schools. Specifically, the idea of consolidating city and county schools.

"It's the fear of city kids coming out into the schools districts and vice versa," Rochester Mayor Bill Johnson says. "This is the last beachhead they've got to defend. Schools, in their opinion, is where the line has got to be drawn."

As previously reported in City Newspaper, merging towns or schools districts would be a very complex, contentious, and lengthy process. Such mergers require state legislation --- in some cases amendments to the state constitution --- and public votes or referenda.

"Cities and counties can't be merged without a change in state law," Johnson says. "My words are very clear. My intent is unambiguous. I don't have any consolidation plans."

Often overlooked in this whole thing is the fact that city kids are already in suburban schools, thanks to the Urban-Suburban Interdistrict Transfer Program. The program's goal is to increase the percentage of minority students in predominantly white suburban schools. It was started voluntarily by city schools in 1965 to combat "de facto" segregation caused by housing patterns.

This year, 390 city kids in grades 1 to 12 are being educated in the Brighton, Brockport, Fairport, Penfield, Pittsford, West Irondequoit, and Wheatland-Chili school districts.

The kids, on the whole, do very well, says the program's director.

"Like any school district, you have kids that are very successful, kids who are middle of the road, and kids who this is not a good match for," says Theresa Woodson. "It works for a majority of students and families."

The program, Woodson says, helps break down boundaries and misconceptions each group might have about the other.

"It gives you the opportunity to say, 'This is my experience,'" she says.

City schools spokesperson Barbara Jarzyniecki says her schools get a bad rap.

"Our achievement scores are lower than our suburban counterparts, but we also have a lot more challenges," she says. "We have the same behavioral problems that they have in the suburbs: fights in schools... ."

Remember the bomb threats that followed September 11? Jarzyniecki says that was a bigger problem in the suburbs, not the city.

She invites anyone who thinks there's a difference between city and suburban schools to visit city schools.

What would they find?

"The same things they find at other schools," Jarzyniecki says. "Teachers teaching and kids learning."

Speaking of...

Latest in News

More by Christine Carrie Fien

-

Building up

Mar 29, 2017 -

Hetsko's heart

Mar 15, 2017 -

Squeezing starts at GateHouse-owned Daily Record and RBJ

Feb 28, 2017 - More »

More by Christine Carrie Fien (FORMER)

-

Sticking it to the 19th Ward

Apr 21, 2004 -

After Amo

Apr 14, 2004 -

Of bonds, bridges, and bravado

Apr 14, 2004 - More »