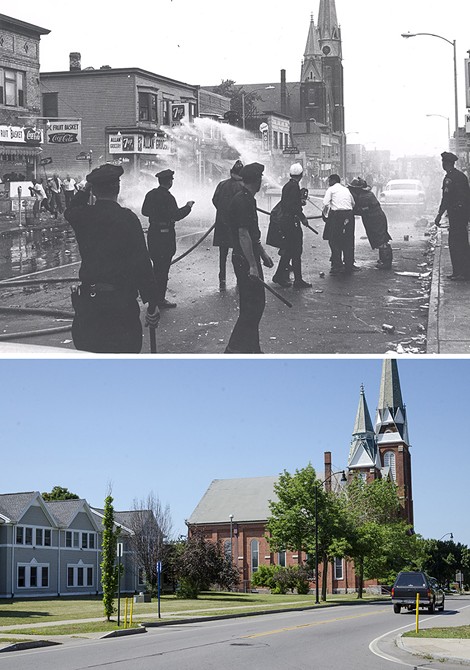

A look back: Riots of '64 still haunt Rochester

50 years later, fear still shapes our community

By Mark Hare

Photo courtesy the City of Rochester, Rochester, New York. Rochester Images (www.libraryweb.org/lh/Rochester_Images)

[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Editor's Note: This article was first published in July 7, 2014, as a retrospective of the Rochester riots that took place 50 years earlier.

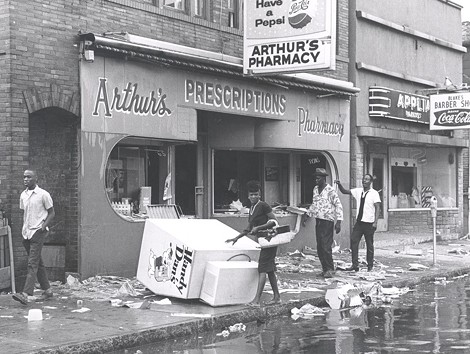

The riots that forever changed Rochester began on July 24, 1964, at a Friday night street dance on Joseph Avenue. A chaperone asked two police officers for help with an intoxicated young man. The officers arrested the man, but a crowd surrounded them to prevent the police from taking him into custody. The officers called for backup and more police arrived, including the K-9 unit — a source of tension for years, with blacks insisting that the dogs were unnecessary and that using them to facilitate an arrest was inhumane.

The dogs may have been the match tossed into the dry tinder of years of frustration and anger. Rocks and bottles were thrown and before long, store windows were being shattered. A mob swept through the Seventh Ward, looting stores and rushing past peacemakers such as Mildred Johnson, who ran a neighborhood unemployment service and tried to calm the crowd. Police Chief William Lombard, who was popular in the black community, walked alone into the angry crowd and pleaded for reason. The rioters ignored him, too, and then overturned his car and set it on fire.

The rioting, or revolt as it is sometimes called, continued until morning despite the presence of hundreds of police officers. On Saturday night, the disturbance reignited and spread to the Third Ward, with rioters looting stores along Clarissa Street, Jefferson Avenue, and South Plymouth Avenue.

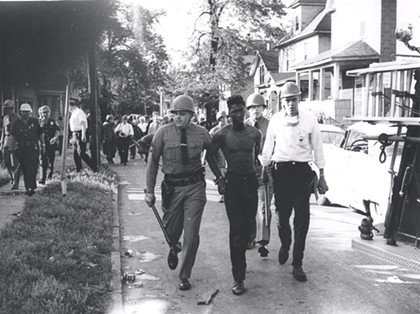

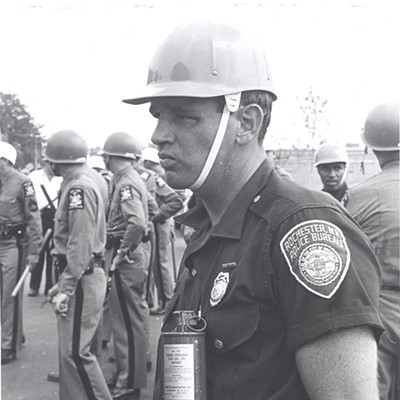

On Sunday afternoon, 1,500 National Guard troops arrived to help restore order. When the smoke lifted, property damage topped $1 million, 350 people were injured, and 800 had been arrested. But the life-changing consequence of the riots was not property damage or physical injury, or even the four tragic deaths, but the fear the city sucked deep into its lungs — a fear that has shaped the community that Rochester has become.

In the decade after the riots, "whole neighborhoods seemed to just pack up and move across the canal into Gates or into northeast Greece," says Paul Haney, a Monroe County legislator and a former member of Rochester City Council.

Not that all was well before the riots, of course. White Rochesterians had actually begun their exodus years earlier. Some no doubt feared an increasingly black city, but others merely took advantage of accessible FHA mortgages designed to aid the construction of suburban neighborhoods. The riots accelerated the exodus, in other words, but were not the only cause.

And though Rochester's black population tripled to more than 25,000 during the 1950's, the newcomers did not have the high-level skills needed for employment in the manufacturing sector, and the city's iconic industries did far too little to recruit and train them for jobs. Black unemployment was over 10 percent.

Meanwhile, thousands of jobs went unfilled and unemployment for whites hovered below 2 percent.

The city's leaders seemed oblivious to the changing demographics and the pressure cooker that unemployment and overcrowded housing was creating in the city center — despite high-profile police clashes with black citizens.

In August 1962, for example, police arrested Rufus Fairwell while he was closing the service station where he was employed. He was accused of refusing to identify himself; he suffered two fractured vertebrae in police custody and was eventually cleared of any wrongdoing.

Most blacks were clustered within a few city blocks; houses built for one or two families had four or five mailboxes on the front porch. Overcrowding was endemic; the 1960 Census found that 35 percent of the housing units in the Third and Seventh wards were deteriorated and dilapidated. Lagging behind other upstate cities, Rochester built just two affordable housing projects during the 1950's.

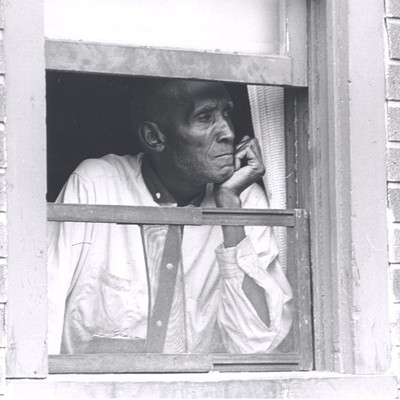

It's an oversimplification to say that the anger that exploded that July night was the product of Third World housing, high unemployment, and stifling temperatures. But thousands of black people came to Rochester expecting to build better lives and found only better public assistance benefits. Their despair was bound to find its voice sooner or later.

So where are we 50 years later? The poor are effectively "detained" in their neighborhoods, says Carvin Eison, a Rochester filmmaker and director of "July '64," a 2006 documentary about the lasting impact of the riots. (Eison is filming a sequel — "July 2014.") In the original film, Minister Franklin Florence, the first president of the local civil rights organization FIGHT, says that the big problems in 1964 were "health, education, and jobs." Not much has changed in 50 years, Eison says.

Census data analyzed in an exhaustive report released last December by the Rochester Area Community Foundation reveals that Rochester has become the fifth-poorest city in the country. Despite huge increases in state and federal aid, the city lacks the resources to repair its neighborhoods, to expand services for children and seniors, or to attract young families and businesses, the report says.

Our schools are among the worst in the country. And while the city school district has begun a $1 billion program to renovate and retrofit its crumbling schools, there is no countywide plan to be sure that city children get the quality education they are promised by the state Constitution.

The fear that drove Rochesterians to the burbs is like the lead dust that has poisoned Rochester's children. It worked its way through the vital organs and then settled deep in the bones, shaving points off the social and political IQ we need to solve these problems.

The residents of this county are good people; when the calls go out for volunteers to read with city children, prepare Thanksgiving baskets, or collect winter clothes, thousands of hands are raised. And yet, when you ask how we can reverse this decline, the response is a collective shrug of resignation.

Middle-class suburbanites have worked hard to build successful lives for themselves and their children, and many believe that Rochester's poor just need to do the same. They welcome minorities who have "earned" the right to a suburban ZIP code, but they bristle at proposals for more affordable housing in their towns or to open their excellent schools to impoverished city children.

But to see poverty as the consequence of weakness or laziness is to miss what urban poverty has done — isolated the poor not just from "stuff," but from the connections and tools they need to know how to get that stuff.

Traditionally, cities in America have responded to middle-class flight by annexing adjoining towns, growing their tax bases, and giving suburbanites a personal stake in the success of the city. New York put an end to that practice in the 1920's, freezing its cities in 100-year-old footprints.

New York's 19th century system of local government has codified the ridiculous notion that a city, 19 towns, 10 villages, and 19 school districts, tightly squeezed into a mid-sized county, have such distinct interests that they require separate governments. Legally, there is no Community of Monroe, as folks here once described themselves, and the last communitywide response to the city's decline was a sales tax redistribution plan — 30 years ago.

In Monroe County, too many people have become comfortable with walls between city and suburbs, white and black, affluent and poor. Any whisper of city-suburban school partnerships to mitigate the impact of high-poverty city schools on learning is met with a predictable narrative: "Integration" equals "forced busing" equals dragging innocent first graders from Brighton and Pittsford to some hellhole school in the city where the teachers are inept and the black students will beat up the white kids.

Never mind that it's been 40 years since the Supreme Court struck down busing across district lines to relieve segregation resulting from housing patterns or other de facto reasons.

This is the legacy that fear has bestowed on Rochester: good people frozen in time, unwilling to imagine, let alone try a plan to reverse the city's slide into poverty and despair.

Prominent Rochesterians say and have said for years that regional solutions are needed for the city's problems. But it is rare for them to publicly endorse any specific ideas for the biggest challenges — public safety, housing, and education; they saw how former Mayor Bill Johnson was destroyed during his campaign for county executive when he suggested countywide schools.

"You know the definition of a pioneer?" asks Larry Glazer, the developer who hopes to reinvent Midtown and much of downtown Rochester. "It's a guy in the desert with an arrow through his heart. Nobody wants to get too far out in front."

Is Rochester finally more open to change? Maybe. Sandra Parker, president and CEO of the Rochester Business Alliance, and others say that there is a genuine commitment to dealing with both poverty and education, which is essential to the community's economic health. Local business leaders are mining an anti-poverty report done last year by a mayoral commission in Richmond, Virginia, for strategies that could be adopted in Rochester. There are many other community conversations under way, as well. Will any of this talk lead to fundamental change? Not without a big dose of courage.

Shrug off the great shrug

Many people here hold that Rochester's decline was inevitable, partly the result of a global economy that decimated the city's 20th century industries (which it did), and partly the result of personal choice (to move out for greener pastures).

But there were many junctures over the past 50 years when different decisions surely would have set Rochester on a different path. Here are three:

• A broad cross section of public and private sector experts (called the Greater Rochester Intergovernmental Panel) labored from 1972 to 1975 to develop recommendations for sweeping changes to government services, under the auspices of the National Academy of Public Administration. The GRIP-NAPA report called for a two-tiered system of local government that would have retained local control of many services while consolidating key functions: police, fire, ambulance, housing development, human services, and others — at the county level. The idea was to provide better service at a better price, but the real virtue of the plan was that it would have required local governments to work together for their shared future.

The report's authors noted with prescience that while they'd been told not to address public school collaboration, "We only do half the job in remaking local government...without considering the various serious needs in education."

Most of the panel's recommendations were ignored.

Democrats, who captured a City Council majority in 1973, were worried that county Republicans (who had been the champions of metropolitan solutions in the late 1960's and early 1970's) would effectively take control of the city if restructuring were put in place. "In my political career, there is only one thing I really regret," says Haney, who was elected to City Council in 1973 and was asked by Mayor Tom Ryan to be the city's point person in the GRIP-NAPA deliberations. "I had my marching orders — to drag my feet — and I happily complied," he says. "If some of the things they recommended had been adopted, we'd be a much different community today. It was a lost opportunity."

• A second missed opportunity came with the gutting of the state's Urban Development Corporation, established in 1969 for the purpose of building low-income affordable housing in cities and in suburbs. With the authority to override local zoning regulations, the UDC built large complexes across the state, including projects in Greece, Perinton, and Webster. These developments, rather than attacking concentrated poverty, moved it to the suburbs. Opposition in the 1970's led the State Legislature to strip UDC of its ability to build without local approval. The smarter course would have been to require UDC to build smaller townhouse developments.

• A third opportunity came in 1983 with the referendum for a consolidated county police force that would've spread the cost out to everyone in the county and begun to address the causes of the city's decline — population loss, a shrinking tax base, and rising costs. After its defeat, the city and county agreed a year later to the Morin-Ryan sales tax formula that gave the city a much larger share of county sales tax revenue. The sales tax plan was essential to the city's fiscal survival in the short run, but it was also an excuse for not moving toward a sustainable form of local government.

The way forward

"We have a culture of poverty now and the lack of will to do anything about it," says Leonard Brock, director of educational initiatives for the Children's Agenda. "And this is much more challenging than poverty itself."

Indeed, if there is any consensus among the roughly 30 community leaders interviewed for this piece, it is this: Doing nothing leads nowhere, but doing what needs doing will test this community as never before.

Proposed remedies for Rochester's poverty settle into two broad categories:

• Major policy initiatives to address chronic inequities — notably the development of affordable housing in and outside the city, and having high-quality public schools available to city and suburban students. It's not that jobs and economic development are suddenly lesser issues, but Rochester has for too long aggressively courted business while ignoring the obvious: great schools and decent housing are the keys to city neighborhood revitalization, which can only make Monroe County more attractive to employers. These are preconditions for reinvestment.

• A wide range of actions to energize and engage the poor in ways that will help build community and allow them to take a more active role in decisions that affect their lives.

First, the latter. Poverty is much more than not having enough money. In Rochester and many inner cities, isolation and the lack of engagement are even more dire problems. Transportation (to and from jobs, to child care, to full service grocery stores) is a huge obstacle.

Many poor people are unconnected to primary health and dental care. They have unreliable or partial cell phone or Internet services. They do not have a network of friends and professional colleagues who can alert them to opportunities for training or youth summer jobs. They do not have experience at being advocates for their children's education. They are often "under-banked," relying on predatory lenders and check cashing establishments.

In short, they are outside the mainstream of society's network of opportunities and connections.

"We need access and information," says the Children's Agenda's Leonard Brock.

Engaging marginalized people is critical to change. Poor people are not stupid; bringing them into the decision-making process is the way to make the best decisions for the common good. There are organized efforts in Rochester to expand the conversation on the city's future. But engagement must be broad, deep, and result in action.

It's hard to assess whether there is a trend in this direction. But here, in no particular order, are some of the strategies being tried or planned.

• Efforts to connect existing training and education programs to assure that those who enter the pipeline emerge at the other end with a job. Major public and private funders want to support organizations that collaborate to minimize duplication and maximize outcomes, says Simeon Banister, who runs a fund-raising consulting firm, administers a self-help initiative called Save for Success (which provides an 8-to-1 match for students who save a small amount for education or training), and chairs the Greater Rochester MLK Jr. Commission, a nonprofit that promotes nonviolence, economic justice, and community empowerment.

An abundance of training programs exists in Rochester, Banister says, but those programs may not always connect directly to jobs. With funding, the MLK commission could hire a team of "navigators" who would become fully familiar with the educational programs aimed at employment. They would develop an online database of programs that would help providers move students through the pipeline — from basic training for high school youth to higher level programs. The idea is to link training and jobs more closely to assure that once someone is in the pipeline, the path to employment is clear.

• Churches should focus on building community and promoting self-reliance. "Churches should stop seeing themselves as having a mission of survival and start seeing themselves as having a mission of discovery," says the Rev. Matthew Nickoloff, pastor of the new South Wedge Mission, a small Episcopal-Lutheran congregation on Caroline Street. Nickoloff, a Fairport native who studied at Princeton and Duke Divinity School, describes himself as the "poster boy for privilege." He says he doesn't know what poverty feels like, but he does know what it means to be a good neighbor.

Pastors should ask their members to commit to living in transitional neighborhoods for a period of time, Nickoloff says, to bring stability to those areas. Churches should open their buildings to host community meetings, cafes or musical events, to provide child care, to be present to their neighbors, he says.

Similarly, the Rev. Lewis Stewart, a veteran civil rights activist and head of the United Christian Leadership Ministry, says that black churches have become insular and should re-engage their communities. Congregants should have a higher profile in the neighborhoods around their churches, he says.

"We have to say to black people, 'You have to change,'" Stewart says.

No one wants to live in neighborhoods where there is an epidemic of violence and drugs, he says, and churches must help people find ways to turn themselves around.

• Build diverse networks. For example, Clay Osborne, a retired vice president for human resources at Bausch and Lomb and the former director of operations for Monroe County, says that he would love to see a campaign asking employers to commit to hiring one person of color over the next year. Employers who say they can't find qualified minorities should look harder, Osborne says.

"Don't change your standards or lower your requirements," he says. "But maybe prolong your search."

That one new employee will be connected to an informal network that will help the employer hire more minorities, Osborne says. It's a small step, he says, but that is how change happens.

• Connect the poor to financial institutions and credit. At ESL Federal Credit Union, Ajamu Kitwana, the newly hired program manager for consumer prosperity, is working on strategies to reach out to poor people who are "under-banked" — that is, people without bank accounts or debit cards or a credit history that can open the door to car loans and mortgages.

"Social challenges present opportunities," Kitwana says. As a credit union, ESL is chartered to serve this region and to engage low-income customers who are outside the financial mainstream. It's a win-win, he says. ESL makes money by helping the poor utilize financial services to their own advantage.

• Making healthier choices. Learning healthier habits can be another point of entry for poor people to connect to the opportunities that middle-class families have long enjoyed.

"People think they can't be healthy because they are poor," says Candice Lucas, director of community health services for the University of Rochester Medical Center's Center for Community Health. "You may not be able to afford a gym, but you can be active."

The center runs several initiatives, including Rochester Walks, a program that has developed safe walking routes in many city neighborhoods to encourage fitness. The interaction with clients gives the staff a chance to explain the health benefits of fitness, Lucas says, and to help clients get medical care they need but didn't know they were covered for through Medicaid or other insurance. It's about making connections, Lucas says.

There are things that we can do

As critical as engagement is to the effort to reverse poverty, none of these steps will be successful without the housing and education policies that would have been much easier to implement 30 years ago when the city was less poor and the county was much wealthier.

What should these policy initiatives produce? A city where families and businesses do not face an unusual financial risk by investing in city property and a city where schools are so good that no one moves to escape them.

The heyday of state and federal housing programs may be over, but opportunities still exist, says Stuart Mitchell, president and CEO of PathStone Corporation, a developer of affordable housing and provider of other services to low-income communities.

Federal tax credits enable developers to build affordable family housing, and several hundred units have been built in suburban Monroe County over the years, he says. "But even if there were no (political) resistance to affordable housing," Mitchell says, "I don't think we (the Rochester community) could do more than two projects a year with 100 units each because there is so much competition for the credits."

Still, over a decade that could make a substantial difference and help break down the reluctance of many towns to welcome low-income families.

It's been several years since Crerand Commons, 48 townhouses for low-income families, opened in Gates, and Supervisor Mark Assini says he would welcome additional units. Assini says he supports efforts to end the concentration of poverty. He says he has always believed "in pulling yourself up by your bootstraps," but that individual initiative is not enough to lift families who have been trapped in poverty for generations. The Crerand Commons families moved from the city for a better life and better schools, Assini says.

Assini says that he's taken some heat for his views on poverty, but that he isn't bothered by it. "I am a Republican, but I'm also a Catholic," he says, referring to the church's historic commitment to justice for the poor.

Watch the trailer for "July '14," a documentary about the current state of Rochester through the lens of the '64 riots, produced at Rochester Community Television and directed by Carvin Eison. Find out more about community events commemorating the riots at RCTV's website.

Incentive zoning (granting a special permit or zoning variance in exchange for a builder's commitment to add a certain number of affordable housing units) is a tried and tested tool that has largely been used to leverage senior housing, but it could be used to build family units as well.

A third idea, Mitchell says, is to create a private fund that would provide a rent subsidy — say, $300 a month — that low-income families could use to supplement their own resources to rent an apartment of their own choosing in the suburbs. All that's missing is a generous foundation with a million bucks or so to invest.

The point is that there are ways to support and grow economically diverse communities, if there's the will to do so. The same basic concept is true for schools.

Fifty years of research and experience have shown that high-poverty schools fail. Put those same poor students into schools with a healthier socioeconomic mix and they do much better academically with no adverse impact on their more affluent class classmates.

Some urban areas have consolidated school districts (not going to happen here because the legal and political hurdles are too high), but there are other voluntary ways to erase high-poverty schools. Open multiple countywide magnet schools, primary and secondary, with programs attractive to city and suburban families. Triple or quadruple the size of the existing Urban-Suburban program. Look for ways that suburban districts can partner with the city on programs — which could provide better integration and utilize excess building capacity in suburban districts.

Simple, but not easy. The path forward is mined with political and logistical obstacles. We tend to focus on white suburban objections to integration efforts, but there are likely to be objections also from black families in the city.

"I don't believe any black child learns better sitting next to white children," the Rev. Lewis Stewart says. "I think that idea is wrong-headed, and Urban-Suburban is wrong-headed. Why can't we pour money and resources into these (city) schools?"

Similarly, Leonard Brock of the Children's Agenda says that he no longer believes socioeconomic integration is the only way to go. Union City, New Jersey, has made great strides in turning around high-poverty schools with a huge infusion of state money, he says.

And there are legitimate questions about how funding for magnet schools would impact district budgets, about rising poverty populations in several districts, and about the impact on teacher union contracts.

But these are challenges that other communities have started to address. Can Monroe County do the same? Rochester Mayor Lovely Warren, who was not available to be interviewed for this piece, has repeatedly called for broad-based solutions to the city's multiple crises. And yet, it has been decades since the city and county have exercised their intergovernmental muscles to reverse the city's inexorable decline.

Ed Doherty, recently retired vice president of the Community Foundation and principle author of its poverty report, says the newest Census numbers show that Rochester is on track to a 5 percentage point increase in poverty by 2020, which would put the city where Detroit is today.

"As a municipal entity, Rochester is no longer viable," Doherty says. "From a fiscal point, Rochester has survived only with dramatic increases in state aid. The poverty report put that number at a 175 percent increase over the past 15 years."

That's a dramatic increase, but amenities such as recreation and libraries have been cut back as public safety expenses rise, he says. The Rochester school district, too, has seen a dramatic increase in state aid, with 81 percent of its budget now attributable to the state and federal government.

How long can Rochester survive? Impossible to say, Doherty says. The state seems committed to enough aid to maintain life support, he says, but a turnaround will be much more difficult.

One way forward is to set goals, he says. Doherty's idea is a loose framework he calls the 10-10-10 plan — a commitment to lift 10,000 Rochesterians out of poverty (65,000 city residents now live in poverty), create housing for 10,000 poor people in the suburbs (about 3,600 units), and add 10,000 middle-class residents to the city.

These goals would require no governmental restructuring or pose an excessive burden on any particular group. The three goals work together to reduce the concentration of poverty; if the city attracts 10,000 middle-class residents while lifting 10,000 others out of poverty, the impact is multiplied.

It would be worth adding an educational goal to the mix — one that would interact with the others to reduce the impact of poverty. Something like, no schools in the county with a poverty population in excess of 50 percent.

None of this can happen, of course, unless the county executive (a new one will be elected in 2015), mayors, town supervisors, school boards and superintendents, and business leaders agree to step beyond the narrow and parochial requirements of their offices and work for the common good. This is possible, but hardly probable.

This kind of leadership requires creativity, courage, great political skill, and a heart for justice. It requires pioneers willing to risk the arrows for the greater good.

(Mark Hare retired in 2012 after 28 years as a columnist, reporter, and editorial writer for the Democrat and Chronicle and Times-Union. From 1978-1984, he was a reporter and columnist for City Newspaper.)