[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

The Eastman Museum vault, tucked down a staircase in the center of the museum’s sprawling expanse — is two stories high and packed with artifacts. Mahogany Sweetheart Stereoscopes, where two lovers could belly-up and flip through images together, sit beside Macintosh desktops and a “Paparazzi” action figure playset. Acting as an unofficial guide, Technology Collection Manager Damien Spader presents what resembles a giant drawing compass and places a brass viewfinder on top. He parts a black curtain to reveal a small table.

“This uses the same technology as the camera obscura, but would have probably been used in architecture,” he said. “The person pulls up a chair and is able to transcribe by the projection.”

The camera obscura Spader referred to is one of the earliest forms of light capture, possibly used by Aristotle and written about in a 1545 book on astronomy for its use in eclipse studies. The camera obscura and its later progression, the pinhole camera, have always been safe viewing tools — from the last time a total solar eclipse followed this trajectory in 1925 (coincidentally the same year George Eastman retired from Kodak), to the homemade versions people continue building today.

On the second floor of the George Eastman Museum mansion, a square room is shrouded in darkness. Black velvet curtains lay heavy against the floor, and it takes more than a few seconds for average eyesight to adjust. When it does, and depending on the time of day, the light shining out from a small hole nestled into the window refracts the West Garden onto the wall, upside down and backwards.

This is a camera obscura: a pinhole projecting light into a dark room or onto a dark surface. While the camera obscura was fantastic for transcription, the image was fleeting so it was, ultimately, a viewing platform. As people wanted to capture and keep their photos, the big dark room became a small enclosed box known as the pinhole camera.

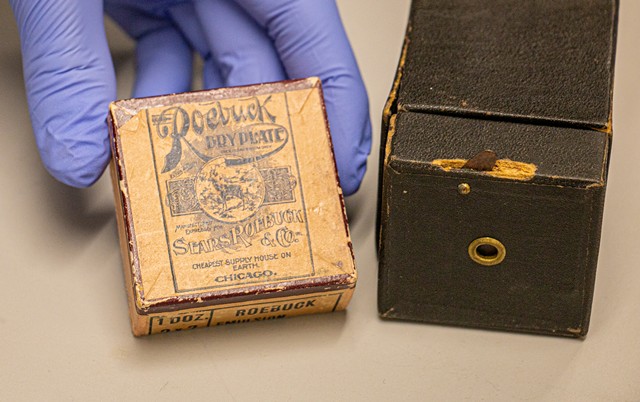

The museum’s collection shows how utterly simplistic they were — made of wood or cardboard and tape. Unlike the camera obscura, light-sensitive glass lenses or paper could be loaded inside. Simply opening the aperture for a second or two captured the image.

Today, people continue to make pinhole cameras to view eclipses. In fact, it’s as easy as throwing an old Staples cardboard box together with a square of hole-punched construction paper and some tape — which is exactly how Ted Kinsman, associate professor at RIT in the School of Photographic Arts and Sciences, makes one in about five minutes.

Kinsman turns an overhead projector on and angles it at the box. With all the lights off in the lab where his students sometimes shoot fruit, a circle of light refracts onto the wall.

“Any object, any shape, can act as a pinhole,” Kinsman said. “But since you’re not looking directly through a lens it’s very low-intensity, so it’s not going to burn your eyes out.”

Looking at the cardboard box, it’s hard to not find it all romantic. Standing with the light behind him, as the solar event would be, Kinsman tracks the moon’s movement.

“There’s our pinhole image,” he said, pointing to the dot. “If that’s the sun, you’d see the circle of the sun as it would go through the eclipse.”

The box made with junk is, in essence, what Eastman might have been using to see the eclipse, as well as many before him. It’s that simple; that easy.

“I think we’ve always found interesting ways of capturing,” Spader said. “And I think with something like the eclipse, being that it only happens every hundred years or so, my mind goes right to that Kodak moment.” eastman.org

Jessica L. Pavia is a contributor to CITY.

“This uses the same technology as the camera obscura, but would have probably been used in architecture,” he said. “The person pulls up a chair and is able to transcribe by the projection.”

The camera obscura Spader referred to is one of the earliest forms of light capture, possibly used by Aristotle and written about in a 1545 book on astronomy for its use in eclipse studies. The camera obscura and its later progression, the pinhole camera, have always been safe viewing tools — from the last time a total solar eclipse followed this trajectory in 1925 (coincidentally the same year George Eastman retired from Kodak), to the homemade versions people continue building today.

On the second floor of the George Eastman Museum mansion, a square room is shrouded in darkness. Black velvet curtains lay heavy against the floor, and it takes more than a few seconds for average eyesight to adjust. When it does, and depending on the time of day, the light shining out from a small hole nestled into the window refracts the West Garden onto the wall, upside down and backwards.

This is a camera obscura: a pinhole projecting light into a dark room or onto a dark surface. While the camera obscura was fantastic for transcription, the image was fleeting so it was, ultimately, a viewing platform. As people wanted to capture and keep their photos, the big dark room became a small enclosed box known as the pinhole camera.

The museum’s collection shows how utterly simplistic they were — made of wood or cardboard and tape. Unlike the camera obscura, light-sensitive glass lenses or paper could be loaded inside. Simply opening the aperture for a second or two captured the image.

Today, people continue to make pinhole cameras to view eclipses. In fact, it’s as easy as throwing an old Staples cardboard box together with a square of hole-punched construction paper and some tape — which is exactly how Ted Kinsman, associate professor at RIT in the School of Photographic Arts and Sciences, makes one in about five minutes.

Kinsman turns an overhead projector on and angles it at the box. With all the lights off in the lab where his students sometimes shoot fruit, a circle of light refracts onto the wall.

“Any object, any shape, can act as a pinhole,” Kinsman said. “But since you’re not looking directly through a lens it’s very low-intensity, so it’s not going to burn your eyes out.”

Looking at the cardboard box, it’s hard to not find it all romantic. Standing with the light behind him, as the solar event would be, Kinsman tracks the moon’s movement.

“There’s our pinhole image,” he said, pointing to the dot. “If that’s the sun, you’d see the circle of the sun as it would go through the eclipse.”

The box made with junk is, in essence, what Eastman might have been using to see the eclipse, as well as many before him. It’s that simple; that easy.

“I think we’ve always found interesting ways of capturing,” Spader said. “And I think with something like the eclipse, being that it only happens every hundred years or so, my mind goes right to that Kodak moment.” eastman.org

Jessica L. Pavia is a contributor to CITY.

Latest in Culture

More by Jessica Pavia

-

Growing a community

Mar 27, 2024 -

Make to last

Feb 8, 2024 -

Pull up a chair

Dec 21, 2023 - More »